It is a truth universally acknowledged among wonky introverts that derive their identity from the contents of their minds over the coalition to which they belong that the left-right political spectrum must be in want of an overhaul.

The political spectrum is one-dimensional for a reason: conflicts tend to come down to two sides. If there aren’t the factions will join up or split until there are. Each side will have a center of gravity, and since we can draw a line between any two points there will be a spectrum. All was well until the sticklers objected. It wasn’t just that no single side appealed to them, but that no point on the line between them did.

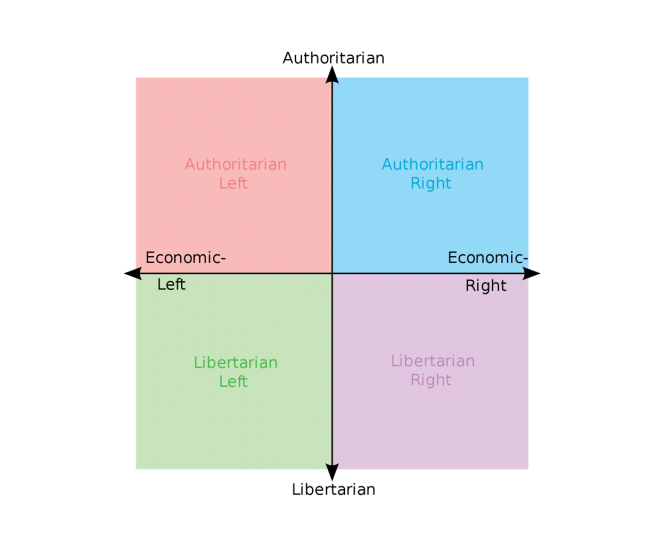

So the political compass was invented.

It augmented a mostly economic left-right axis with a social axis ranging from the “authoritarian” to the “libertarian”. This allowed its most vocal fans to express their distinction by congregating in the lower right corner, which is underserved by electoral politics but popular among people who liked to argue politics on the internet 15 years ago.

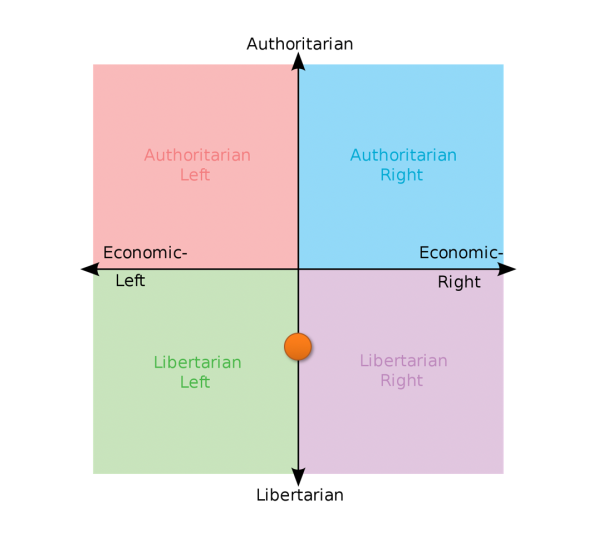

The compass became wildly popular but I’ve never been a big fan. Part of the reason is that one tends to be underwhelmed by classification models that don’t result in a clear position for oneself. The compass doesn’t work for me, as I tend to wind up here:

This isn’t an accident or error, it’s a correct result for me given how the model is set up. But I still don’t get an identity and I doesn’t “do anything” for me. There’s no sense of insight.

However, this isn’t just about my personal dissatisfaction. I have some better objections.

When I worked as a consultant I made more of these 2-by-2:s than I can remember, and over the years I worked out a few rules of thumb for how to make good ones:

- The axes should be independent or close to it. That means statistically independent as in “uncorrelated”, not just logically independent as in “not the exact same thing”.

- The axes should be inputs, ideally simple and as close to “fundamental” (whatever that means) as possible. They’re what explains, not what needs to be explained.

- Each end of the axes should be equal. They should be equally interesting, equally important and sometimes, if possible, equally good. If they’re outcomes (as in scenario planning) they should be approximately equally likely and one should not simply be the absence of the other (i.e. not “thing happens” vs. “thing doesn’t happen”.

- Something novel should emerge in the quadrants. Each intersection ought to be more than just the axis values put together. Interaction ought to produce a result with its own identity that we can recognize as a thing over and above its axis values[1].

I don’t think the political compass does very well according to these standards.

I’ll give it a pass on independence. It’s not perfect, since placing real politicians on it tends to yield a stretched blob from the bottom left to the top right, but I can accept that as partly an artifact of coalition politics as described above.

But the meanings of “left” and “right” are complex and it strikes me as more of an outcome than a basic attribute. The same applies to the authoritarian-libertarian axis. Few think of themselves as “authoritarian”, and those who are, aren’t so for shits and giggles — you don’t value repression for its own sake (and they don’t call it repression) but in the service of something, and that thing is more fundamental.

The axis (and the whole compass) is championed mostly by those with a libertarian bent, and freedom is central to them. But their opponents aren’t anti-freedom as such and defining them like that are going to be incorrect, and furthermore, loaded in a way we ought to avoid when making these models (as per rule three).

Also, “social issues” as commonly defined doesn’t stand out as a natural category to me. The axis that does exist seems to be what you’re permissive about and what you aren’t, more than how permissive you are across the board. It seems so if you constrict “social issues” to being about sex and drugs, but include political correctness, environmentalism and guns and it all looks less coherent except to the small minority the political compass was apparently made for.

The compass breaks my last rule most of all. Good 2-by-2:s are supposed to be “insight porn”, where everything falls into place when the axes are combined. This doesn’t happen. The quadrants don’t even get their own names! Look:

They’re just called “libertarian left”, “authoritarian left”, “authoritarian right” and “libertarian right”. That’s it? That’s a failure in my book. Yes, you get some feel for what each quadrant is like, but they don’t seem to map on to the real political landscape all that much. All the memes built on the model portray them as, in order: hippies, stalinists, nazis and pseudo-Randians. That’s fun for playing internet weirdo games but it doesn’t in my opinon describe the real political world particularly well, since it sacrifices explaining most of the landscape for some funny stereotypes at the extremes. It puts me at “half hippie and half pseudo-Randian”. Thanks, that’s certainly one mix of falsehood and old news.

I want to suggest another way to produce a similar structure, but better according to my rules. I don’t expect it to inspire any memes, but it does result in what I consider to be real groupings, emergent and internally complex, out of what I similarly believe are more fundamental underlying psychological factors (attitudes and stances more than policy preferences).

•

Cognitive decoupling transplanted

I’ve written a fair bit about cognitive decoupling. Here’s Sarah Constantin describing the idea:

Stanovich talks about “cognitive decoupling”, the ability to block out context and experiential knowledge and just follow formal rules, as a main component of both performance on intelligence tests and performance on the cognitive bias tests that correlate with intelligence. Cognitive decoupling is the opposite of holistic thinking. It’s the ability to separate, to view things in the abstract, to play devil’s advocate.

/…/

Speculatively, we might imagine that there is a “cognitive decoupling elite” of smart people who are good at probabilistic reasoning and score high on the cognitive reflection test and the IQ-correlated cognitive bias tests. These people would be more likely to be male, more likely to have at least undergrad-level math education, and more likely to have utilitarian views. Speculating a bit more, I’d expect this group to be likelier to think in rule-based, devil’s-advocate ways, influenced by economics and analytic philosophy. I’d expect them to be more likely to identify as rational.

I used the concept in my article about the skirmish between public intellectuals Sam Harris and Ezra Klein last year:

High-decouplers isolate ideas and ideas from each other and the surrounding context. This is a necessary practice in science which works by isolating variables, teasing out causality and formalizing and operationalizing claims into carefully delineated hypotheses. Cognitive decoupling is what scientists do.

/…/

While science and engineering disciplines (and analytic philosophy) are populated by people with a knack for decoupling who learn to take this norm for granted, other intellectual disciplines are not. Instead they’re largely composed of what’s opposite the scientist in the gallery of brainy archetypes: the literary or artistic intellectual.

This crowd doesn’t live in a world where decoupling is standard practice. On the contrary, coupling is what makes what they do work. Novelists, poets, artists and other storytellers like journalists, politicians and PR people rely on thick, rich and ambiguous meanings, associations, implications and allusions to evoke feelings, impressions and ideas in their audience. The words “artistic” and “literary” refers to using idea couplings well to subtly and indirectly push the audience’s meaning-buttons.

In discussed it further and developed it into a broader concept in Decoupling Revisited and boiled it down to this in Postscript to a Podcast:

At its most general it just means looking at a single issue/question/idea/fact at a time. Related ideas, implications and associations etc. can only be brought in explicitly and with the consent of all parties. Contextualizing, on the other hand, means that all associative connections between ideas are valid and count as relevant if any party thinks they are.

Now I’ll continue to milk it by applying it to politics[2].

Decoupling is about ideas: how are they connected? By any association or only by strict logic? What’s the default relationship? Connected and you need to prove isolation (difficult or impossible), or separate and you need to justify a connection by willing agreement or by proving it beyond reasonable doubt?

Now what if we replace ideas with people?

In decoupled society the default relationship between two people is that of no obligations whatsoever (special circumstances like friendship or family bonds don’t count since we’re talking about the macro scale). The only obligations are to respect explicitly stated rights and agreements. No expectations beyond that are valid (for example, between employers and employees). Social problems can and should be adressed with formal means: contracts, property rights, tort law. Political decouplers like money and the market as institutions because they quantify and decontextualize social obligations.

In coupled society what it means to be a good person or what may be required of you at any point is open-ended. There are not clear boundaries between people and you are expected to take others’ or society’s interests into account as much as your own. Anything you do that plausibly affects anyone or anything outside yourself is everybody’s business; duties are not fully specified and can never be completely discharged or fulfilled. Social problems can and should be adressed by everyone taking on themselves to be more self-sacrificing and focus less on what rights they have to do what they want. Political couplers dislike money and the market for the same reasons decouplers like it[3].

Coupling and decoupling[4] as moral stances are obviously politically relevant. How about as factual stances? At least as much. According to a decoupled view, human beings are built from the inside out. They have traits, tastes and behaviors that results from a combination of inborn nature, rational thought and acts of will, and social structures are the emergent result of them interacting. In the coupled view, human beings are created from the outside in. They’re lumps of clay shaped to perform the roles assigned to them by a system tending to perpetuate itself, and individual selves are the emergent result of socialization into these roles[5].

•

Thrive and survive

Is that “left” and “right”? A little bit, yes, but it’s by no means the entire difference. There’s definitely a right that celebrates conformity and fitting in, obedience to authority and tradition, and there’s also a left that insists on their right to be and do what they want without restriction or condemnation.

We need something more. And remembering my first rule of thumb, it should be something as independent from the decoupling dimension as possible. The answer came to me right away in the form of this article from a few years back, where Scott Alexander defines left and right as “thrive” and “survive” type values:

My hypothesis is that rightism is what happens when you’re optimizing for surviving an unsafe environment, leftism is what happens when you’re optimized for thriving in a safe environment.

The Dead Have Risen, And They’re Voting Republican

Before I explain, a story. Last night at a dinner party we discussed Dungeons and Dragons orientations. One guest declared that he thought Lawful Good was a contradiction in terms, very nearly at the same moment as a second guest declared that he thought Chaotic Good was a contradiction in terms. What’s up?

I think the first guest was expressing a basically leftist world view. It is a fact of nature that society will always be orderly, the economy always expanding. Crime will be a vague rumor but generally under control. All that the marginal unit of extra law enforcement adds to this pleasant state is cops beating up random black people, or throwing a teenager in jail because she wanted to try marijuana.

The second guest was expressing a basically rightist world view. The prosperous, orderly society we know and love is hanging by a frickin’ thread. At any moment, terrorists or criminals or just poor management could destroy everything. It is really really good that we have police in order to be the “thin blue line” between civilization and chaos, and we might sleep easier in our beds at night if that blue line were a little thicker and we had a little more buffer room.

The article goes on to give several examples but this is the gist. In a “survive” scenario (think famine, war or zombie apocalypse) mistakes are costly, outsiders are potential threats, keeping order is paramount and we can’t afford to be too generous towards the weak lest they pull us down with them. Only serious dangers are real problems and risk and discomfort are things we need to deal with.

In a “thrive” scenario by contrast (think true post-scarcity in a future automated economy), where we don’t even need to think about making a collective living we can afford almost limitless generosity towards the “other”, the non-useful, the few antisocial, the sensitive and the non-conformist. As we get richer we work towards eliminating ever smaller risks and discomforts.

This also captures a big part of left and right but not all of it, and I think the decoupling dimension picks up the remainder perfectly. For example, Scott A says that the thrive-survive model struggles with explaining why school choice is rightist, which the decoupling axis can handle.

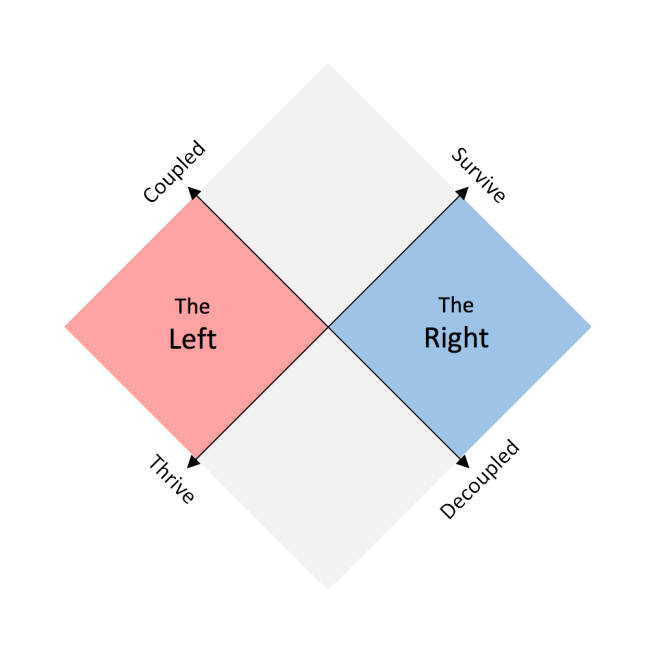

Towards Left and Right

Think of the combination “coupled” and “thrive”. We’ve got far-reaching, non-enumerated duties toward the common good and self-sacrifice as the solution to problems. We don’t need to be concerned with survival/productivity and therefore don’t need to be stingy towards the needy — especially since somebody’s problem is everybody’s problem. So we distribute the costs of individual weaknesses, mistakes and misfortunes throughout the population because we can afford to deal with them and nobody has the right to refuse.

This “we’re rich” plus “we’re in it together” produces a love for grand public works and programs meant to help and nurture the people in various ways. The fact that this requires taxation is not much of a problem since wealth is produced by the system as a whole anyway[6]. The reason we’re not currently using our society’s wealth to satisfy everyone’s needs is that some (the rich) are hogging more than their fair share. Restrictions on behavior is mostly in service of combating this inequality in access to resources and the power it brings. This is close to the essence of the modern political left.

Putting “decoupled” and “survive” together yields the right. Here everybody is responsible for themselves and their loved ones only. You have your list of rights and obligations but anything more is strictly over and above what is required. Civilization is kept running by the productive and thus being productive must be rewarded and being unproductive or even destructive must be punished or at the very least not supported or society will stagnate or worse. You’ll suffer the consequences of your own mistakes and misfortunes because you must learn to improve, be an example to others — and because nobody else is obligated to clean up after you.

“We’re not rich enough” plus “limited, enumerated obligations” produces a skepticism of social programs deemed overly ambitious, intrusive, coddling or frivolous. The solution to poverty is the production of more wealth, which requires incentivizing the productive — the disciplined, smart, self-sufficient and responsible — to do so. Restrictions on behavior is mostly in service of cultivating these traits.

Putting the two dimensions together and tilting the whole thing so the left goes on the the left and the right on the right gives us this:

It’s very hard (and a popular internet pastime) to try to pin down the difference between left and right but I think this is them, in as pure a form as I’ve ever seen.

•

End of part 1.

In part 2 we’ll look at the other two quadrants and their tricky relationships to the left-right dichotomy.

UPDATE: Part 2 is here.

• • •

Notes

[1]

In fancy words: we want nonlinear interaction effects.

[2]

Actually, that’s not fair. This isn’t a farfetched idea coming out of thinking about this concept excessively. I thought of it immediately after writing about decoupling for the first time so it’s more of a core feature than an exotic expansion.

[3]

I suspect a large part of the attraction of strongly coupled political ideology like communism is due to dissatisfaction with the formalized, sterilized, and from a social and emotional perspective, grossly distorted relations (both towards each other and to work itself) that results from the use of currency as the most important or only way to allocate obligations. Note this quote from Red Plenty, a book about the economic aspirations of the Soviet Union:

Marx had drawn a nightmare picture of what happened to human life under capitalism, when everything was produced only in order to be exchanged; when true qualities and uses dropped away, and the human power of making and doing itself became only an object to be traded.

Then the makers and the things made turned alike into commodities, and the motion of society turned into a kind of zombie dance, a grim cavorting whirl in which objects and people blurred together till the objects were half alive and the people were half dead. Stock-market prices acted back upon the world as if they were independent powers, requiring factories to be opened or closed, real human beings to work or rest, hurry or dawdle; and they, having given the transfusion that made the stock prices come alive, felt their flesh go cold and impersonal on them, mere mechanisms for chunking out the man-hours. Living money and dying humans, metal as tender as skin and skin as hard as metal, taking hands, and dancing round, and round, and round, with no way ever of stopping; the quickened and the deadened, whirling on.

And what would be the alternative? The consciously arranged alternative? A dance of another nature. A dance to the music of use, where every step fulfilled some real need, did some tangible good, and no matter how fast the dancers spun, they moved easily, because they moved to a human measure, intelligible to all, chosen by all.

I read this as an expression of disgust at how modern market economies are systems where economic relations are stripped of their social elements, of feelings, intentions, meaning and will, turning it all into a machine. It needs to be machine. Machines work. But it will never feel quite right for most of us.

[4]

This could be called “individualism” vs. “collectivism” but those words are worn and overused to the point that they no longer can be used to communicate anything specific. What does it mean, and feel like, to be an individualist or collectivist?

[5]

These two assumptions have some impressively divergent implications that leads to opposing perspectives on many, many issues. Having this one contradiction underneath the surface of public discourse condemns whole continents of conversation to dysfunction. It needs to be addressed openly and explicitly so that at least a little bit of consensus can be built as a basis on which to hold meaningful debate.

[6]

This might be slightly off. In my experience a lot of popular (far-)leftism appears to conceive (in a partial narrative way) not of “wealth” that’s “produced” but of “resources” — a choice of word that evokes the naturally occurring — that simply exist and are to be “distributed”. The right, of course, does the opposite pointing-out-vs-overlooking dance.

Intriguing model for sure, I’m curious to see where you take this in part 2.

LikeLiked by 1 person

How do you like my political quiz, proud sir? https://enopoletus.github.io/quiz/

“Scott A says that the thrive-survive model struggles with explaining why school choice is rightist”

It’s not. School choice is a delusion of the super-rich, and is rejected by those not super-rich, whether right or left. Doesn’t matter if those rich vote hard Dem or hard GOP. Cf., the 2016 MA charter cap referendum.

Anyway, on your axes, I identify as strongly “Decoupled” and on varying points between “Thrive” and “Survive”, depending on how that axis is defined.

LikeLike

I looked at your quiz but I was honestly put off by the starkness of the choices (and I don’t care much for international policy which took up much of it).

Maybe that’s the nature of school choice where you live, but it’s not we’re I live. It’s a reality here, and fairly common.

LikeLike

“Maybe that’s the nature of school choice where you live, but it’s not we’re I live. It’s a reality here, and fairly common.”

Again:

https://www.nytimes.com/elections/2016/results/massachusetts-ballot-measure-2-expand-charter-schools

It isn’t a “where you live v. where I live” thing. It’s reality. You may simply be confused.

“and I don’t care much for international policy which took up much of it”

Not good. America’s internal policy doesn’t change much. Its external policy is a hundred times as important.

LikeLike

In case it hasn’t been clear: I’m not American.

LikeLike

Fascinating. Which country?

LikeLike

The Advocates for Self Government have used versions of a two-dimensional, four-quadrant political plot since the ’80s (and it goes back even further to the ’70s, when it was called the Nolan Chart because Libertarian Party founder David Nolan introduced it). Sometime around the early ’90s they turned it diagonally just like you did, making left and right be actually left and right, and libertarians on top and authoritarians on the bottom. The two axes were “Social” and “Economic”, though.

https://www.theadvocates.org/quiz/

LikeLike

Right. This is by no means a new model, that’s not really the point. It’s rather to get exactly the groups we’re used to seeing, but from a different direction.

LikeLike

The chart in this article: https://quillette.com/2019/03/04/how-swedens-blind-altruism-is-harming-migrants/ uses the axes “Survival vs. Self Expression” (somewhat similar to your survive/thrive axis), but the other one is Traditional vs. Secular/Rational. It’s referred to as the “Inglehart–Welzel World Values Survey cultural map wave 6”, and it’s arranged rectangularly without any obvious orientation to “left/right” in the standard political sense.

LikeLike

I doubt if the Traditional vs. Secular/Rational has anything to do with the Coupled vs. Decoupled axis. The secular societies include Japan, which is not exactly decoupled.

LikeLike

That better frameworks for discussion have existed for decades makes this post even more tragic. Looking forward to part two & will use this in my taxonomy of the subset of unproductive discussions I’m familiar with – those about how research information should be shared & assessed.

LikeLike

Well you’ve done it. You replaced the political compass that suited me fine (left individualist) with one that puts me in the position you were in. I’m definitely on the thrive side, and when it comes to thinking styles I’m a high decoupling programmer, but when it comes to relations between people I identify about equally with coupled and decoupled, and when it comes to the human nature vs social construction question, to me the obvious answer is false dichotomy, it’s a little of both. But this isn’t just wishy-washiness, I feel quite fervently about this! To my ears the question sounds like “Do you prefer the sort of authoritarianism with death camps or reeducation camps?” Because one view implies the key to a harmonious society is to keep the wrong people out of it, and the other leads to believing that people are arbitrarily moldable and the key to a harmonious society is remaking them. I only want people with nuanced, impossible to pin down views on human nature in my politics, leave the straightforward opinions for other issues!

LikeLike

Well, them’s the breaks, somebody will get screwed out of a clear identity. What can you do?

Of course dichotomies like these are ultimately false, but I think our balanced, complex views can often be arranged in a signal-corrective way between two poles.

And honestly, “reeducation camps” gives me the absolute creeps. Ignoring the severe moral problems with forcibly trying to reshape people into what you think they should be, they don’t even sound that different from death camps considering the massive risk (and history very much agrees with me here) of “reeducation” turning into mass murder when people don’t respond as malleably as expected. (But that’s an indictment against any categorical imposition of a consistent vision on society.)

LikeLike

Hmm.

I think the “Decoupled-Thrive” quadrant is a pretty good match for a lot of libertarians and anarchists. As is the case in much of the left, the continued stability of civilization is taken more or less for granted; questions like “but if we abolish this binding legal institution how will society continue to function” are more likely to be laughed off. And as is the case with much of the right, ‘rugged individualism’ tends to be the most strongly promoted notion for how people ought to live and regulate themselves.

The thing that separates the anarcho-libertarians from the left is their lack of faith in “coupled” social institutions; the thing that separates them most from the right is their belief that society is in enough danger that “survival” ethics are called for, enabling an extremely firm stance on abstract principles like “absolutely no state coercion” and “absolutely no state interference in private lives.”

Conversely, I think “Coupled-Survive” politics lend themselves to authoritarianism and totalitarianism. The prevailing ideology sounds something like: “The People are a single unit, bound together by a shared background no one can ever break. But the People are menaced by sinister outside enemies, betrayed from within by those who are not of the People. Only through the most fierce and terrifying action can we win through and secure Lebensraum/The Revolution.”

The thing that separates left-totalitarians from normal leftists is whether “society is threatened by the enemies of the Revolution” is getting used as an excuse to cover up for atrocities- whether ‘Survive’ thinking is being used to excuse acts that would be unconscionable under ‘Thrive’ thinking. Conversely, the thing that separates right-totalitarians from normal rightists would mostly be in how much faith and discipline they put into mass action. Fascist party rallies get [i]big[/i], fast.

LikeLike

I’m curious how your axes might relate to the Big five personality traits.

Intuitively, it seems like Coupling would correlate with Openness to experience, and perhaps Agreeableness. Likewise, a “Survive” attitude seems like it would correlate with Conscientiousness and Neuroticism.

At a glance, it seems like the scientific literature claims the two main personality traits correlated with the Left-Right axis are Openness and Conscientiousness.

For instance:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0092656612001158

I link that particular study because they note an effect which seems particularly relevant to the present discussion:

The authors point out that the correlation between Openness and Conservatism is significantly larger (r = -.422 vs. r = -.066) in societies with a low level of systemic threat (i.e., societies which are “thriving”). It seems reasonable that wanting to change society to aim for the well-being of the people as opposed to mere survival would require a person to be somewhat open to new ideas. It also seems reasonable that such an attitude makes no sense if the society is currently still struggling to survive.

Another study indicates an interaction between Agreeableness, Neuroticism, and social class:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0191886918301466

They found Agreeableness to correlate negatively with Conservatism, except for subjects of low social class. This might be interpreted as Agreeableness manifesting in caring for the well-being of either those closest to you or that of everyone, depending on your available resources.

Neuroticism was also found to correlate negatively with Conservatism for those of high social class. In this case, however, there was also a positive correlation with Conservatism for those of low social class. I find that a little strange, since I would expect an increase in Neuroticism to come with an increase in survivalist, crisis maximizing attitudes.

The only explanation I can think of at the moment is that individuals scoring high in Neuroticism may tend to view their negative circumstances as their own fault, and conversely their positive circumstances as undeserved. This doesn’t seem to map neatly onto the “Survival-Coupling” axes though. Alternatively, perhaps a neurotic person is generally worried about threats to society, but not so much if they are personally well-off.

It might seem like Openness manifests in a “Thrive” attitude in times of social stability and sufficient resources.

Meanwhile, I think Agreeableness correlates with a “Coupled” attitude generally. The reason why it is not negatively correlated with Conservatism for subjects of low social class is probably an artifact of the Right’s alliance with religion.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The coupled attitude should basically map 1 to 1 with Agreeableness – if you think people are basically okay and don’t like conflict, you will want to build a nice harmonious society with them. If you think people are somewhat hit or miss and enjoy competing with them, individualism it is.

An exception might be someone so jaded on society that they would like to just check out and do their own thing as a consolation prize, though they long for community (that one would be heavily correlated with Neuroticism, from my observations).

High Openness would slightly push you to thrive attitude. High Conscientousness would strongly push you to survive attitude, in fact they might be manifestations of the same phenomenon – a tendency to prioritize security and order and actively prepare for threats.

LikeLike

I agree regarding Agreeableness, but I still find it somewhat strange that Agreeableness does not correlate with leftist views if you have low social status.

Regarding Conscientiousness, Openness is more strongly correlated with Left views than Conscientiousness is with Right views, so I think it would be wrong to say Conscientiousness is a stronger push in the opposite direction of Openness. If anything, Openness pushes stronger, provided a low systemic threat to society. At least according to the paper I linked.

LikeLike

I don’t think that associating Coupling with Openness is intuitive at all: I think the reason that I find the vision of the “coupled” world unappealing is because of introversion. A society where “Anything you do that plausibly affects anyone or anything outside yourself is everybody’s business” and “There are no clear boundaries between people” would be one that sends me screaming in the other direction. Openness correlating with Thrive does seem to make more sense.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The “main sequence” (bottom-left to top-right) can be explained if the thrive–survive axis is the first principal component and the coupled-decoupled axis is the second principal component.

LikeLike

A counterexample to the theory that the left is more likely to be at the thrive end of the thrive–survive spectrum: global warming.

The Left is more likely to get hysterical about it.

LikeLike

I wish I had the time to adress this and other points in the comments here, but for now I’ll just say that part 2 will clarify some things.

LikeLike

Interesting chart, but I don’t think “the right” fits very well in the decoupled-survive quadrant.

I mean, have you ever met a real conservative? The whole flag-waving, “the nation”, support-our-troops mentality is the exact opposite of the individualistic mindset you’re calling “decoupled”.

“The only obligations are to respect explicitly stated rights and agreements. No expectations beyond that are valid (for example, between employers and employees). Social problems can and should be adressed with formal means: contracts, property rights, tort law. Political decouplers like money and the market as institutions because they quantify and decontextualize social obligations.”

That doesn’t sound to me like any man-on-the-street, Trump-supporting conservative I’ve ever seen. It describes libertarians and perhaps the law-and-economics end of conservatism. You qualify this by stating that this is the “general” rule, “special circumstances like friendship or family bonds don’t count since we’re talking about the macro scale”. That doesn’t make sense to me. Believing that inherent social obligations are mediated through the family and the church doesn’t make one “decoupled”.

You definite it in the cognitive sense like this:

“Stanovich talks about “cognitive decoupling”, the ability to block out context and experiential knowledge and just follow formal rules, as a main component of both performance on intelligence tests and performance on the cognitive bias tests that correlate with intelligence. Cognitive decoupling is the opposite of holistic thinking. It’s the ability to separate, to view things in the abstract, to play devil’s advocate.”

Again, this isn’t “the right” at all. Conservatives are terrible at this! Maybe worse than those on the left. The only thing bringing “the right’s” average up is the libertarian quarter.

So really, I think “the left” is coupled-thrive and “the right” is coupled-survive. Anyone who is “decoupled” is outside the spectrum of “normie” politics.

And on a more fundamental level, I don’t find the whole thrive-survive thing compelling. That suggests that socialism and redistribution are “good in theory but bad in practice”, i.e. bad only because they’re unaffordable. But I reject them because I believe “a need is not a claim” on someone else’s production; i.e. I reject the egalitarian-altruistic impulse that says everyone is supposed to value everyone else’s needs equally.

I think a better and more fundamental distinction than “thrive-survive” is the distinction between “everyone should value everyone else equally” and “people have special obligations to themselves / their groups”. Call it universalizing-particularizing.

Decoupled-universalizing: scientific socialism / effective altruism

Coupled-universalizing: utopian/religious socialism / normal Democrat

Coupled-particularizing: family, folk, fatherland / normal Republican

Decoupled-particularizing: Objectivists and deontological libertarians

LikeLike

I wish I had the time to adress this and other points in the comments here, but for now I’ll just say that part 2 will clarify some things.

LikeLike

> They’re just called “libertarian left”, “authoritarian left”, “authoritarian right” and “libertarian right”. That’s it?

The version I originally saw had the top-right and bottom-left as conservative/right and liberal/left, and the other two quadrants as authoritarian and libertarian. I wonder how this version came to be more common…?

I’m probably more decoupled, but I’m pretty sure I’m more left/liberal than libertarian (e.g., I’m in favor of basic income and of health care paid by the state (if it can achieve its intended purpose well)) and I’m definitely not conservative, so I’m not sure how I fit into this…?

LikeLike

I wish I had the time to adress this and other points in the comments here, but for now I’ll just say that part 2 will clarify some things.

LikeLike

I imagine coupled+survive is a time when reform is no longer possible. There every policy or reform proposal is a deeply symbolic act indicating where you stand on everything. For example, disbelief in life after death in 1st century Judaea was strongly linked to the Jewish priestly class and Roman occupation. Belief in Resurrection became the default position of dissidents.

Immigration is another area where, although everyone agrees reform is needed, there is no way to actually implement any since the issue has taken on such symbolic overtones and is now embedded in warring stories of national identity.

LikeLike

I had sort of an epiphany related to the coupled/decoupled axis, connecting a few ideas. For starters, there is a closely related dimension about who you are coupled too. Valerie K gets at a similar idea but I’m thinking along the lines of this paper, explaining the connection between modern vs traditional values and the prevalence/promotion of kin-based vs non-kin-based social networks:

http://www.jstor.org/stable/25487644?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

The other idea is that your nature/nurture outside-in/inside-out distinction points at two different evolutionary processes – biological evolution and memetic.

Half of the connection should be obvious if you read the paper, which points out that values associated with kin based networks lead to large family sizes and promote competition and fitness with regard to biological evolution. But it should also be the case that urbanization, diversity, and broad social networks should lead to increased memetic competition, which should lead to a memetically fit culture that spreads modern values

Culture and biology are shaped by two different evolutionary processes that don’t necessarily push them in the same political direction. This creates an axis of political conflict. So on this axis you throw your weight behind and are supported by an evolutionary process – either biological or memetic.

If you are on the biological end, you may value your culture but you believe culture mostly spreads from parents to children, or at least it should. You fear immigrants won’t assimilate and they may come to outnumber you. You fear your culture is fragile and your kids might be converted. You are distrustful of institutions that spread culture, which seem to be under the control of the other side. (You might see a conspiracy at work here but it’s really just because you are up against an evolutionary process. This makes you feel powerless.) You feel cultural influence is a particularly insidious form of power, and are relatively less concerned about more overt forms of power. You support traditional family values.

If you are on the memetic end, you figure immigrants’ children will assimilate into our culture, but you have a more nebulous idea of what that culture is. You don’t see your culture as fragile because it is constantly changing and you view exposure to other cultures as a central part of your culture. You are distrustful of power but don’t see cultural influence as a kind of power. Wherever culture seems like it should change but doesn’t you see insidious forms of power at work. (But you may just be looking at the results of human nature, the product of an evolutionary process.) You don’t believe in human nature, but it concerns you how easily demagogues on the other side appeal to people’s base emotions.

LikeLike

This comment might be related to why the coupled/left association doesn’t seem to fit with my personal views, because I consider my views to be more on the inside-out/decoupled end, but also completely different from what you’re describing as the “biological end”, and I prefer non–kin-based groups.

I think this is mainly because the traits I care most about are traits where people tend to differ from their parents/family (e.g. anything LGBT, anything involving neurodivergence), and I have some tendency to assume other traits work like those (i.e., people have a nature which isn’t necessarily similar to their genetic relatives—which is different from either of the options you’re talking about). People with such traits, if they’re sufficiently uncommon, might grow up not knowing anyone like them (which, at least to me, led to me feeling disconnected from what in theory should be my culture—hence, decoupled), and finding non–kin-based groups is important in that situation since such people wouldn’t fit in well with their family. It also means that trying to keep cultural purity by restricting immigration doesn’t make sense to me, because as long as people are having kids, some of them won’t fit into the culture anyways.

LikeLike

Also see “A Thrive/Survive Theory Of The Political Spectrum” by Scott Alexander

LikeLike

Hmm, after thinking about this a bit I think I’ve come up with a catchier name for the ‘decoupled-coupled’ axis: Liberty versus Duty. You could understand it in terms of Negative Liberty versus Positive Liberty, but I’ve always felt that the term ‘Positive Liberty’ was a mistake and Isaiah Berlin shouldn’t have used such a loaded term. Understanding it in terms of Liberty and Duty makes things simpler: Liberty is about what you *can* do, while Duty is about what you *must*do. For example, in America voting is a right: it is something you can do. Meanwhile, in other countries voting is mandatory: it is something you must do, upon pain of legal punishment.

Both Liberty and Duty are vital components of Freedom (Liberty is what Freedom is, Duty is what makes Freedom possible for all), but some people emphasize Liberty more and dislike the implications of Duty (e.g. conscription), while others emphasize Duty more and dislike the implications of Liberty (e.g. freedom of association leading to people self-selecting into segregated neighborhoods – see https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2002/04/seeing-around-corners/302471/, the section on “Mr. Schelling’s Neighborhood”, though I recommend reading the entire thing). Most people fall in-between, though in a way I personally find hypocritical and unprincipled, supporting whatever they want to do/no do with whatever principle (Duty/Liberty) is most convenient at the moment.

(For example, the people saying “We don’t have an infinite duty to intervene in other countries to stop humanitarian disasters, America is not the world’s policeman.” – they’re often the ones trying to police others for incorrect thought and preach an infinite duty to intervene in every possible manifestation of discrimination. I would respect them more if they were consistently in favor of Liberty or consistently in favor of Duty, instead of consistently in favor of whatever’s most convenient.)

Anyways, this was all based off my musings about Freedom and how Positive Liberty is a confusion of an abomination. Instead of thinking about Freedom in terms of Negative Liberty and Positive Liberty, it’s more illuminating to think about it in terms of Liberty/Duty/Restraint, a.k.a Can/Must/Cannot. I’ve already covered Liberty and Duty, but Restraint is about the other side of inalienable Rights, which are most frequently expressed in terms of things that cannot be done to you. If you flip that to Active voice, you find that it’s about things you *cannot* do to others, no matter how badly you want to. (This is a similar process to how I reframed Positive Liberty into Duty: flip to the Active voice and go from thinking in terms of things you must be provided to things you must provide others).

All three components are vital to Freedom. Without Liberty, freedom becomes propaganda: a fig leaf of justification atop a bedrock of enslavement. Without Duty, freedom becomes hollow: a soap bubble collapsing upon contact with reality. And without Restraint, freedom becomes monstrous: an open road to crimes against humanity. All three parts are necessary for Liberty to be Liberty instead of a handmaiden to Tyranny.

And to expand upon that last bit about Restraint a little: even if there are no genocides, without restraint, the concept of freedom collapses back down to “To the strongest.”. If the free do not exercise restraint in their freedom, than freedom soon turns into a battle of “To the victor go the spoils.” If freedoms do not respect other freedoms, instead adopting a policy of “Woe to the vanquished!”, then free people will fight each other tooth and nail to protect their favorite freedoms from becoming the spoils of war. And war, of course, has a way of destroying what is being fought over.

Anyways, what do you think?

LikeLiked by 1 person

First of all, thanks for making the effort to contribute. I appreciate it.

I understand what you mean, although it doesn’t quite resonate with me and it gets a little to abstract for me to fully appreciate near the end.

In the end changing the axis may well yield a very similar result (I did a lot of such changes in the “Variations on the Tilted Political Compass” post), but with the “decoupled” thing I was looking for something more psychological than your more theoretical version. Specifically whether engaging with random others is about *obeying explicit rules and agreements* or if you’re *obligated to consider their needs an wants generally*.

LikeLike

Thanks for replying. I think though that using recognizable words like ‘Liberty’ and ‘Duty’ would help people understand this system better than words like ‘coupled’ and ‘decoupled’. When you say something like “One is about respecting explicit agreements and not demanding too much beyond that, while the other is about implicit obligations and open-ended requirements to do more good.”, I think people will only remember a vague cloud of words if it doesn’t immediately snap to something recognizable like Liberty vs. Duty. And people have to remember your argument to be persuaded by it after all, and to persuade others.

Now, it might be more accurate to call it Decoupling vs. Coupling, but you have to cut right to the heart of the matter for ordinary people to care at all – you only have five words (https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/4ZvJab25tDebB8FGE/you-have-about-five-words). People just don’t have a very long attention span. And it might be good, as well, for even long-form thinkers to have strong concept handles (https://notes.andymatuschak.org/z5vA4vw86DKNq22xt6pRWhumeRmSzwV6hxRHE). Even though I’m good at remembering my own words, I’ve found it better to have sharpness in my writing rather than clouds of words gesturing vaguely at an association space. Why say

“In decoupled society the default relationship between two people is that of no obligations whatsoever (special circumstances like friendship or family bonds don’t count since we’re talking about the macro scale)… In coupled society what it means to be a good person or what may be required of you at any point is open-ended. There are not clear boundaries between people and you are expected to take others’ or society’s interests into account as much as your own.”

, when you can say

“Liberty is when you can do what you want if it’s not required of you, and Duty is when it *is* required of you. Some societies are about Liberty, others Duty.”

It’s like the example of Ecclesiastes versus modern English in Orwell’s Politics and the English Language (https://www.orwellfoundation.com/the-orwell-foundation/orwell/essays-and-other-works/politics-and-the-english-language/). Why use many word when one word do trick? And why use a rarefied word when a common word will do the trick? Simplicity is bliss; the writer knows they have achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.

… though I must admit, I didn’t exactly live up to it in my earlier post, did I? But in my defence, I was copying and pasting my thinking writing rather than penning some conversation writing, as I’m doing now. Writing helps my thoughts, hence why I write them all down, but sadly it can’t help the fact that my thoughts are rambling and incoherent. It doesn’t help either that I only copied and pasted part of my thoughts, omitting some context that I thought wasn’t needed but is actually important. So let me try presenting my thoughts again, now edited for clarity:

I was reading an interesting book review (of Age of Entitlement) when I realized that freedom can be its own worst enemy. The book was covering how the political polarization of today can be traced back to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, because it (in the book’s words) set up a ‘second constitution’ (end book’s exact words) that set up a different system of rights and responsibilities than the explicit constitution.). This difference explains why the 1950s level of political polarization was famous low (there’s an anecdote about an old Political Science textbook saying that more polarization would be good for America because Americans only have boring establishment parties instead of anything that reflects the full spectrum of their beliefs), and why polarization has been getting worse since then.

Drilling down on what exactly the difference was, I concluded that it was a matter of Positive Liberty versus Negative Liberty, but more important (and overlooked by the book) was the difference between various Positive Liberties. The first constitution (the 1789 one) was about Negative Liberty: people could do things without interference, and the government’s job was to ensure there was no interference, especially by not interfering itself or raising taxes to pay for such interference. The second constitution (the 1964 one) was about Positive Liberty: the absence of interference wasn’t enough, people deserved more, and the government’s job was to provide that. Very noble stuff.

The problem is the zero-sum nature of positive liberty. Negative Liberty ain’t much, but everyone can share in it without a fight – it’s non-rivalrous, one person having it doesn’t affect another person’s ability to have it. Positive Liberty meanwhile *is* rivalrous – money and attention spent on Gay Rights, for example, is not money and attention spent on Black Lives Matter. Hence the phenomenon of the Oppression Olympics – the competition is inevitable when there really is a zero sum battle over a fixed supply of headlines and available government spending. One’s gain is another’s loss, and thus another’s loss is your gain.

Thus, politics has been transformed because the nature of the thing being fought over has changed. Freedom has turned into it’s own worst enemy, because one person’s freedom now intrudes on another person’s freedom. For example, freedom of association for gay communities sometimes leads to them openly excluding black people, and in turn freedom of speech for black communities sometimes leads to them being shockingly misogynistic (rap music isn’t known for having positive depictions of women), and in turn freedom of assembly for women sometimes lead to them forming trans-exclusionary communities…

We don’t have a system for managing such conflicts between freedom and freedom, or even the language to understand and dissect it. We only have the language of freedom versus oppression, hence why every side in these conflicts call each other oppressors and the enemies of freedom, and hate each other accordingly. Free people tear each other’s throats out in the name of defending freedom, because they’re defending *their* freedom – without realizing that it’s only *their* freedom. Clearly, the language of Negative Liberty and Positive Liberty we already have isn’t enough to analyze and clear up misconceptions like that.

And after thinking about it for a while, I concluded that this was because Positive Liberty is a lens that gets things backwards. Positive Liberty is about things you are owed. But for every thing that is owed, some one must do the owing. Someone has to provide that which is not already being provided by Negative Liberty. That someone has a duty.

And like that, I had a flash of insight. The problem with Positive Liberty is that it frames things in terms of “You are owed this.” rather than “You have to provide this.” If we used the language of Duty instead of Positive Liberty, people would be less likely to be outraged that the other people are demanding ‘freedom’ while refusing to provide them the freedom they deserve, and more likely to say something like “We all have a duty to each other, but clearly it has limits, I don’t want to be on the hook for everything and anything.” A world where everyone thinks “Would I want to put up with a similar request from another person?” rather than “You’re a horrible person for saying no, you bigot.”, is, I think, a world with cooler tempers in the political realm.

So that’s why I split Freedom into 3 components (Liberty, Duty, Restraint) – to resolve Freedom’s contradictions, I had to look at the tension within Freedom itself. Without this dissection, you get muddled thinking, or worse, marketing speak about how all freedoms support each other and none of us are free until all of us are. With it, you get the clarity of cold hard reality: we all can’t get what we want, because some of us want things from other people they don’t want to provide. The key to managing that is coming to an agreement we can all live with, about what we can do versus have to do versus can’t do, rather than focusing only on what *we* are owed.

TL;DR: I wanted a freedom that still works when extended to everyone.

(And then I remembered your post about the Coupling versus Decoupling axis, which at the time I thought I sounded kind of like Positive Liberty versus Negative Liberty. But it’s kind of more like Duty versus Freedom isn’t it? Duty is generally more of a feeling than a written law, and Freedom is almost never about the freedom to break the law.)

(Also, if you’re wondering why I included Restraint when I didn’t talk about it at all, I think it has to do with a separate set of experiences I’ve had that make me think I might be a pacifist. To be concise, my brushes with anger have left me shaken, and I’m glad I don’t walk around armed. I can’t trust myself with violence. I need more restraint than other people, to the point of an outright ban. And this brush with… loss of self control… has convinced me that freedom is a monstrous thing without restraint. There are some things you can do that you can never take back.)

(Final thing: this may be a double post, I’m not seeing the first time I posted this so I’m posting it again.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think the common advice about writing you describe are limited in their applicability. I often avoid using one simple word in favor or more, and less familiar ones because, in my opinion, the simple common ones often do not, in fact, do the trick. Using a simple and common word imports a lot off baggage, a lot of connotations, and a lot ambiguity. Making new words is about avoiding that, indicating to the reader that you want a clean slate to sketch your concept on.

A lot of writing relies on evoking associations that the reader already has and playing around with them — playing the reader like an instrument, sort of — in line with, rather than slightly against, existing knowledge and intuitions. When you want to establish a concept it helps (at least it does for me) to mess things up a little bit and make the reader chew a little harder, and for a little longer. “This isn’t meant to just flow by and get swallowed right away.” Also, I write the way I write because I write things out the way I’m thinking them, and and I’m trying to communicate how it looks from inside my head. It’s more demanding and thus appeals to fewer people, but it’s the only thing that interests me. (If going by my “Six Kinds of Reading” post, I try to write in a “refactoring” way and that often works against preestablished concept structures).

As for the rest, I guess I agree? I don’t think it’s exactly the same as what I said since the decoupled thing has more to do with duties being vague and unspecified than big.

LikeLike

Hmm, that’s fair. I like my style, it works for me, but it can’t do everything and something else might work better for other people. I personally like playing the reader like an instrument (and it’s interesting to see that other writers have come to the same analogy about how we manipulate readers, tricking them into thinking our conclusions are actually their thoughts, guided apophenia), and I’m used to people not understanding my thoughts because I don’t think the way other people do. But I must admit, I’m still learning a lot as a writer. I probably don’t even have a stable style yet, just latching onto things I like. But hopefully I can come up with one! I can have a unique combination, even if I can’t think of any unique elements.

Also, don’t mind that the Liberty/Duty/Restraint thing being almost completely unrelated to the thrust of what you were saying. I just came up with something I fell in love with (simplicity dissects a complex issue into useful advice: tell people to think about things in terms of an equal exchange of duties instead of one way obligations – kind of Confucian actually, reciprocal duties…), and wanted to apply it everywhere. I must admit, I also wanted to see if I sounded completely insane for trying to reduce a complex real world issue to a textbook trilemma – I swore I must be oversimplifying something. But no, I can actually present my thoughts in a way that makes sense, and I’m glad that one of my old fears grows a little quieter.

Also, have you ever thought about whether the Political Compass might be better represented by a trilemma or something? Squares are boring and cubes are too confusing to look at, so I kind of want some new ideas in the visualization space – e.g. what if politics reduces to 5 factors somewhat like the Big 5 personality traits, or 6 like HEXACO? This is an underdeveloped idea, but I’m sure it’s got promise somewhere, a good data visualization like Minard’s map of Napoleon’s Russian campaign can be worth it’s weight in gold.

LikeLike

I really enjoyed reading this article (including part 2)…

IMO this framing of different political values (and their resulting ideologies) is a lot better than the “original” political compass. I really think that the “thrive-survive” dimension is one of the most important ones in terms of explaining political values (both of individuals and ideologies) along with being quite easily and intuitively understood, while the “coupled-decoupled” spectrum is a bit more abstract IMO it’s still a very important idea to describe different political and social values of both individuals and ideologies.

I guess that the major question/commentary I have with this political “compass” is why certain societies (i.e. the Nordic countries) tend to be found mostly in one corner (for Nordic countries and to some extent Western Europe overall the upper left “thrive-coupled), while the US for example tends to be more towards the bottom right corner (“survive-decoupled”)… If one were to only concentrate on natural resources per capita for example, I would think that the higher amount of them in the US would lead the society there to be less towards the “survive” spectrum than Western European countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark who arguably are more in the “thrive” spectrum than the US is…

But overall, this is the best of all the political “compasses” I’ve seen so far!

LikeLike