[Note: Since part 1 got quite a lot of hits I’ve become a bit self-conscious about the sweeping generalizations I’m about to make. I’m mostly thinking out loud.]

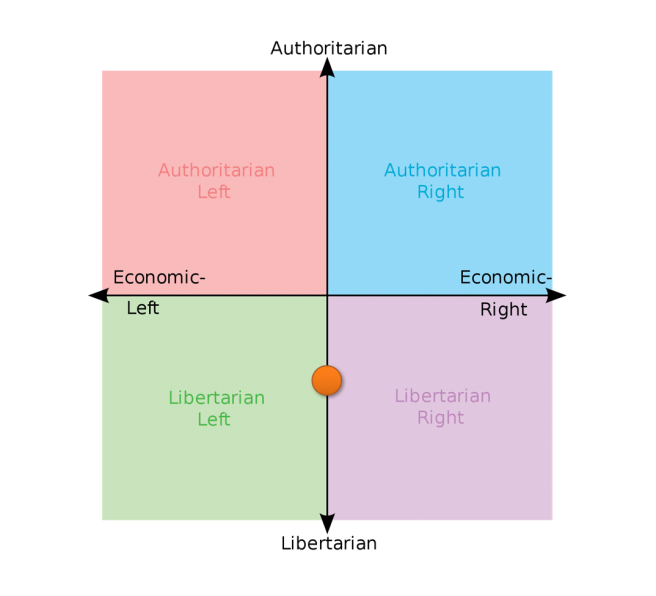

In part 1 I complained about the Political Compass. I said it doesn’t explain much and it’s quadrants aren’t particularly interesting or true to life, all in my opinion as a former professional 2-by-2 matrix maker. That post is somewhat required reading to properly understand this one, but since I can’t count on everybody doing that I’ll summarize it briefly.

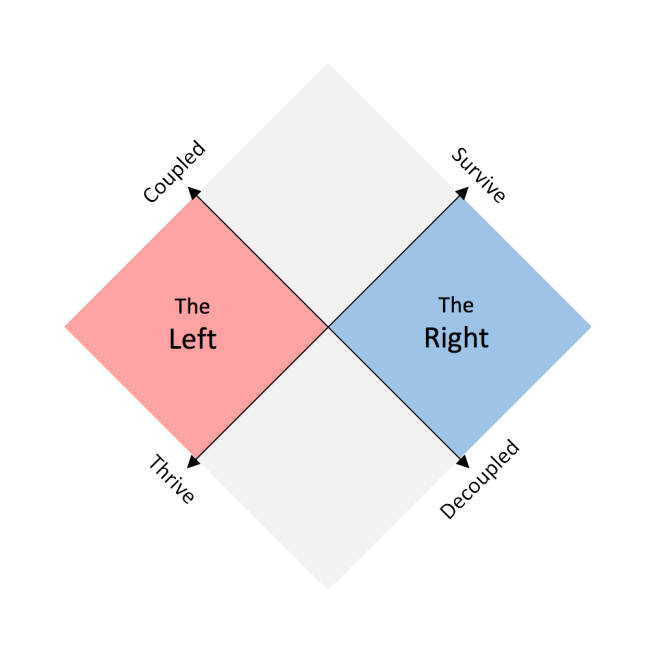

I tried to reconstruct the political compass landscape from two new dimensions at 45 degree angles from the ones the political compass uses. The first draws on the “cognitive decoupling” idea, creating a spectrum between two visions of the ideal society — the decoupled and the coupled.

In the first, people are by default completely separate and all obligations are either formally defined in terms of rights or explicitly agreed to. Interactions with strangers are modeled on arms-length formal transactions, i.e. money and contracts.

In the second, people are by default connected and obligations to others and to society as a whole are open-ended and in theory unlimited. Interactions with strangers are modeled on personal relationships, i.e. empathy, loyalty and unquantifiable debts.

I lifted the other dimension straight from A Thrive-Survive Theory of the Political Spectrum. The “thrive” end are values suitable for safe, rich and comfortable societies where we don’t need to focus so much on making our living and can afford to be generous towards others, the weak, the irresponsible and the unproductive. Self-actualization is the ideal. The “survive” end are values suitable for rough, precarious situations where we do need everybody to be productive, orderly and well-behaved in order for everything to work out. Discipline is the ideal, while personal feelings and wants take a back seat.

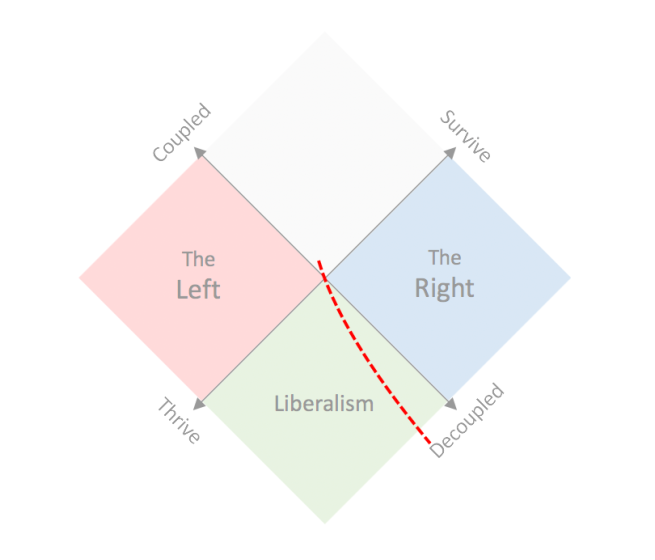

I argue that none of these define the left and the right on their own, but put together they do so as well as anything else does. “Coupled” combined with “thrive” produce the quintessential left, while “decoupled” and “survive” does the same for the right:

Think of the combination “coupled” and “thrive”. We’ve got far-reaching, non-enumerated duties toward the common good and self-sacrifice as the solution to problems. We don’t need to be concerned with survival/productivity and therefore don’t need to be stingy towards the needy — especially since somebody’s problem is everybody’s problem. So we distribute the costs of individual weaknesses, mistakes and misfortunes throughout the population because we can afford to deal with them and nobody has the right to refuse.

This “we’re rich” plus “we’re in it together” produces a love for grand public works and programs meant to help and nurture the people in various ways. The fact that this requires taxation is not much of a problem since wealth is produced by the system as a whole anyway. The reason we’re not using our society’s wealth to satisfy everyone’s needs is that some are hogging more than their fair share. Restrictions on behavior is mostly in service of combating this. This is close to the essence of the modern political left.

Putting “decoupled” and “survive” together yields the right. Here everybody is responsible for themselves and their loved ones only. You have your list of rights and obligations but anything more is strictly over and above what is required. Civilization is kept running by the productive and thus being productive must be rewarded and being unproductive or even destructive must be punished or at the very least not supported or society will stagnate or worse. You’ll suffer the consequences of your own mistakes and misfortunes because you must learn to improve, be an example to others — and because nobody else is obligated to clean up after you.

“We’re not rich enough” plus “limited, enumerated obligations” produces a skepticism of social programs deemed overly ambitious, intrusive, coddling or frivolous. The solution to poverty is the production of more wealth, which requires incentivizing the productive — the disciplined, smart, self-sufficient and responsible — to do so. Restrictions on behavior is mostly in service of cultivating these traits.

In response to questions and criticism

The piece attracted a bit of attention (it was linked from Slate Star Codex among others) and with that some criticism, including some very insightful comments on the post itself. Part of it made me think it was a bad idea to split this post in two parts, since it made part 1 leave some things unclear. For example, some seem to have thought that my characterization of the essences of left and right ought to correspond to the two sides of the political landscape, either generally or specifically in the United States. That’s not the intention and I had hoped that the two blank quadrants left for part 2 would’ve made it clear enough that these are the “cores” of left and right and they’re joined by parts of the other quadrants to form full coalitions.

Another thing that appears to have been misunderstood is the meaning of “decoupling” transferred from ideas to people. I did say “special circumstances like friendship or family bonds don’t count since we’re talking about the macro scale” but perhaps I should have been clearer: it’s not meant to be about valuing social bonds. It’s about your relationship to strangers, or more accurately to the “generic other person”.

You have social bonds to some people like family and friends, which means you owe them to think of them in three full dimensions, to feel their pain, to come to their aid, and to not just respect their interests but make them your own on a deep, emotional level. If you treat them instrumentally, transactionally or in a blind, rule-based way you’ll damage the relationship.

The “coupled” view I’m referring to is the ideal that we treat everyone around us as if they were friends and family. It’s unattainable in practice but still something we’re supposed to try to do if asked, and in any case not explicitly reject. It means that a competitive, transaction-based market society where it’s acceptable to model unseen strangers as objects — as means and not ends that you interact with indirectly through a law-contracts-and-currency interface, instead of fully-fledged fellow human beings you interact with through caring relationships — is on some level deeply wrong. Given this, we get a moral-political vision that is what I described: there’s no clear end to our obligations to think of others. This description of utopian communities is what I mean by seriously extreme coupling.

Decoupling is an explicit rejection of this overwhelming implied duty in the form of demarcation. You have open-ended obligations towards people you have personal relationships with and clearly defined obligations like “respect rights and agreements” toward others, but not open-ended obligations to people in general than can be invoked and/or expanded at any time. “Nobody owes you anything” is a decoupler’s response to perceived overentitlement. It is typically not meant to refer to family and friends.

I might also not have been clear about how the two dimensions interact: they affect each other’s expression. The decoupling property “comes out” differently in the Thrive vs. Survive condition. At the far Thrive end we get something like “the expanding circle” or “a brotherhood of man”: in the limit a duty to feel empathy and personal relationship-like concern for literally everyone. Survive means scarcity mindset, which requires the expansion of concern to have some limit by sheer necessity. Sometimes the limit setting is relatively benign like with civic nationalism but can become increasingly nasty and dangerous when clan, tribe, language, class, religion or race becomes the criterion. In any case the duty extends further than your personal relationships, which is the defining factor.

Overall, I’m still unsure about how robust an idea this is, but I’m certain there something I’m grasping for.

•

Part 2: Up and Down

Now, this is where we left off.

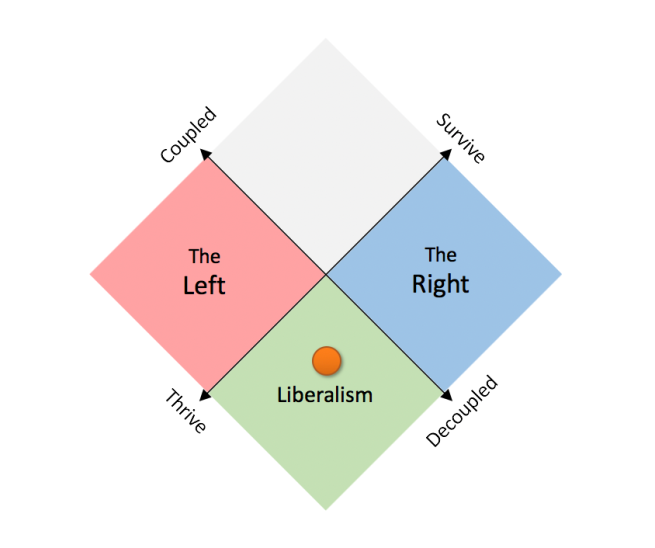

There are two more quadrants to discuss. Lets look at the bottom one first. It’s the combination of “decoupled” and “thrive”, which is the view that society is stable and wealthy enough for us to demand much less discipline and conformity in service of productive organization and risk management than we used to, but that us breaking free from restrictions imposed by our need to weather the slings and arrows of ordinary fortune ought not to be replaced by restrictions in the form of a general duty to serve the interests of others.

For all the problems with the word, this is liberalism as described by me in I, LPC.

To be liberal is to be live and let live. It means acceptance of difference and of pluralism of thought, feeling and action as legitimate and not as a problem to be suppressed. It means tolerance in its classical meaning: accepting the existence of what you’d rather see gone.

Liberalism stands opposed to authoritarianism, naturally. But not just that. It also opposes a communitarianism where your individual needs, wants and rights are subordinate not to the duties attached to your place in a hierarchy, but to the needs and wants of the rest of the community. To be liberal is to strive for everyone’s self-authorship, self-determination and freedom from involuntary obligations, towards either the better off or the worse off.

That opens up a lot of questions about priorities, but this brand of liberalism is less of a full political philosophy than an attitude: profound skepticism towards all restrictions of individual autonomy, whether in the service of stability, efficiency, safety, harmony or equality.

For example, a certain level of fighting poverty through government action is fine, but for liberals, as opposed to leftists, it’s for “thrive reasons”: it increases self-determination on the whole and in a wealthy society we can afford it without imposing too much of a burden on people (especially if the duties are clearly circumscribed and as unintrusive and impersonal as possible[1]). It’s not because we’re fundamentally obligated to make substantial sacrifices for strangers, i.e. “coupled reasons”. In this view, a social safety net is not a right, it’s a privilege — but a privilege we ought to be generous about granting when we’re lucky enough to live in a fabulously wealthy society[2].

I said that one of the reasons I don’t like the standard political compass is that it doesn’t give me a proper identity. I end up on the border between two things I don’t particularly identify with:

But now, look! In the tilted version I have a home!

(This has almost not everything to do with why this model appeals to me.)

•

Varieties of slicing (part 1)

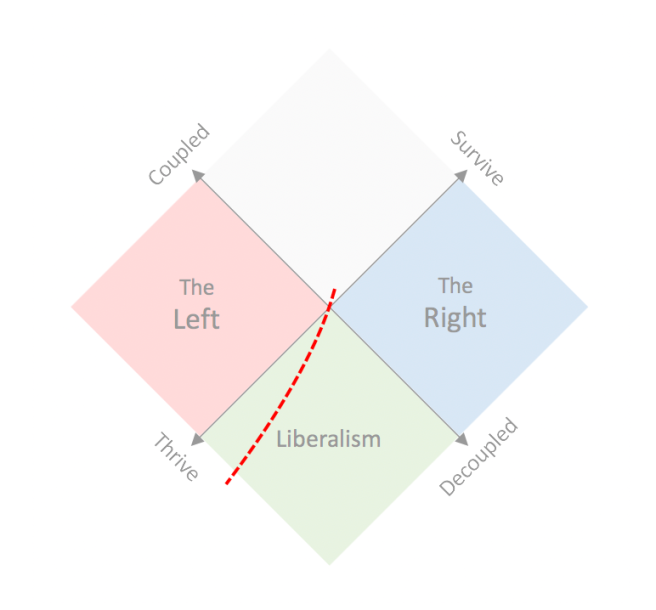

Liberalism is distinct from the right and the left, and has tended to side with the weaker of the two against the stronger. Forcing it into a pure left-right model therefore results in confusion. The differences between the US and Sweden is instructive. In the US, the right is comparatively strong and the left weak, so the political landscape gets cut like this (for two roughly equal coalitions):

This makes Americans feel like the “thrive-survive” dimension is more indicative of left vs. right, and the American labels for the two sides — liberal and conservative — reflect this cutting.

This makes Americans feel like the “thrive-survive” dimension is more indicative of left vs. right, and the American labels for the two sides — liberal and conservative — reflect this cutting.

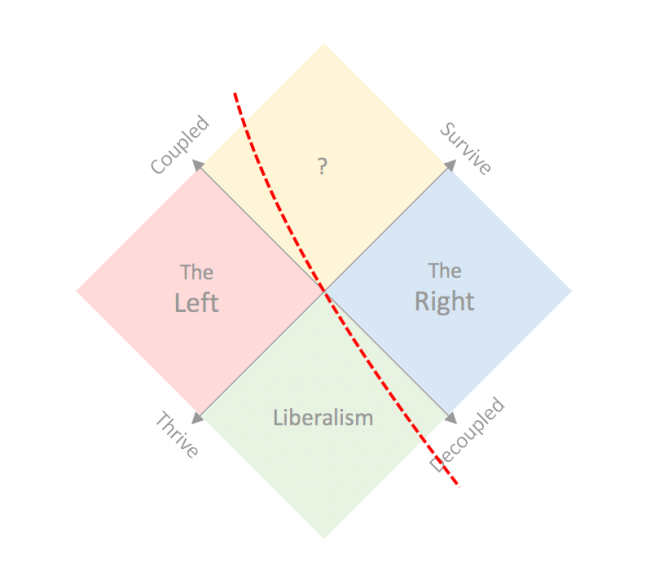

In Europe in general and Sweden in particular the left has been stronger and the political landscape got cut this way:

This makes the coupled-decoupled dimension more indicative of left vs. right and Swedish coalitional labels reflect this: socialist and bourgeois parties are distinguished primarily by their differing attitudes towards public vs. private ownership and management of the economy.

Naturally the American use of “liberal” for “left” drives me up the wall — as a Swedish liberal the difference is rather essential, thank you very much. The phrase “economically liberal” is especially nuts, as it apparently means the exact opposite of economically liberal (laissez-faire)[3].

Interestingly, I think I see the difference between leftists and liberals become more important for Americans as well — at least among the coastal, educated middle classes where outright conservatives are rare enough to make the other two turn on each other in fits of online culture warring, just like game theory would predict. In a pure Thrive environment the ways leftists and liberals agree become nothing more than background scenery and the divisions start to stand out.

This has lead to a game of linguistic musical treadmills where liberals try to claim an identity apart from the left without joining the right, while leftists try to prevent them from doing so. Some liberals choose to adopt the “classical liberal” label but I think that has certain problems. It’s not new, for one. It traditionally separates the very decoupled liberals from the moderately so, rather than separate liberals from the left, and using it amounts to ceding the territory around the plain “liberal” label — home soil! [4] That seems unwise to me. If we’re looking for a label that makes a distinction while keeping the claim to the core territory I’d go with “Actual Liberal”. Just the right amount of on-the-nose.

•

The Problem Child

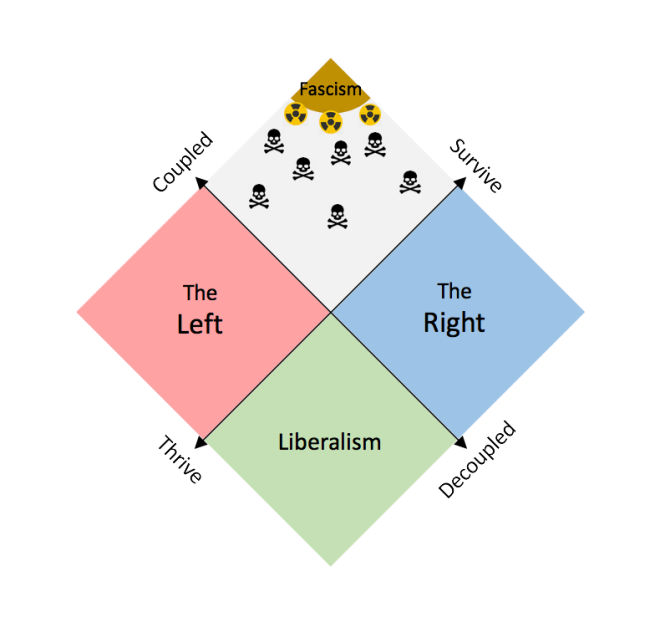

Neat. But aren’t the pictures above missing something? Something big? Like a top quadrant? Yes and there are reasons for that, as we shall see.

While liberalism is easy to identify I struggle with what to call this. I rejected “authoritarianism” as a label in part 1 because hardly anybody is “authoritarian” for its own sake, and I stand by that. Let’s see what else we can get.

“Coupled” and “survive” certainly paints a picture. The world is a tough, unforgiving place and we need discipline to navigate it. Open-ended obligations means you can expect to be helped and supported by everyone else — as long as you contribute and conform. We’re a team and you’re a team player. That’s important, because supporting that kind of cohesion on a large scale requires constant work towards unity. Not surprisingly, this quadrant contains a lot of rhetoric comparing the state to a family, evoking feelings of unbounded support, loyalty and duty.

By serendipity I happen to be reading Bertrand Russell’s The History of Western Philosophy as I’m writing this, and I note that the description of ancient Sparta is a perfect match for the top corner — especially the way it’s neither left nor right. Sparta was militaristic, extraordinarily tough-minded, masculine and with an oppressed serf class, but they also insisted on equality among citizens (and somewhat between the sexes), they hated money, trade and consumerism and aggressively fought accumulation of wealth, and even separated families to practice collective child rearing. Spartan politics were clearly coherent — as coherent as liberalism — but not an extreme endpoint on a left-right spectrum.

There have been versions of “Spartanism”, but the pure form only really came back in full force in the West with modernity and mass society, after industrialization, urbanization and World War I showed what performance civilization-as-fossil-powered-machine is really capable of[5]. That was fascism, which could have worked as a descriptor for this quadrant had it not been turned into a contentless term of abuse. The real, historical fascists believed in something like Spartanism. Internal order was paramount and everyone’s duty towards the collective and its institutionalized form (the state) was essentially limitless. They also thought of themselves, justifiably, as an economic “third way” beyond left and right[6].

It makes sense to put them directly opposite liberalism and between left and right because much of their ideology was a direct rejection of liberal principles but has clear points of contact with both leftism and rightism[7]. Fascism as far-rightism is well-trodden ground. They both agree that competition and the cultivation of competence and strength are absolutely essential for the health of society, making them suspicious of anything that sounds weak, whiny or trivial. With the left they share a distaste for selfishness, instrumentality and the quasi-sociopathic virtuelessness of the market, and agree that it is everyone’s duty think more of the whole than to satisy their own personal desires.

Hardly anybody calls themselves a fascist today, obviously. Part of the reason is likely that actual, capital-F Fascism was soundly defeated and that the nature of its crimes (particularly the Nazi variety) contaminated the whole quadrant to this day, making any settlements there impossible, even at a safe distance from the extreme corner.

That leaves an “identity vacuum” in the moderate north-of-center area. That’s no law of nature; I can imagine a world where it wasn’t the case. Any ideology is bad in the extreme, but it could be normal, theoretically, to be “fascist-leaning” in the way it’s normal now to be a social democrat with socialist sympathies and not want to seize the means of production and shoot all the kulaks, or to be liberal and not want to privatize roads and the justice system, or to be conservative and not want to be ruled by church and crown.

But it is the case: there’s no “mild and respectable” version of fascism.

However, no big settlements doesn’t mean the area close to the center but above it isn’t populated[8]. Oh no. There are plenty of people there, plenty of people who don’t want to be too generous or forgiving towards the undeserving, and also believe in a society where we all owe each other support and sacrifice when we fall on hard times. Who are they?

They tend to be upset at perceived erosion of social trust and believe that it’s because we don’t prioritize rewarding good behavior and punishing bad behavior enough. They’re weary of immigration partly because of its effect on social cohesion — which is considered necessary to maintain fragile, society-wide economic solidarity — and because they suspect some immigrants to not live up to standards of good behavior, especially if they come from countries low on social trust and can be expected to bring such attitudes with them.

They’re suspicious of free trade, transnational corporations and organizations like the EU, partly for rational reasons: globalization’s been good for richer people in the first world and poorer people in the third but not as good for the working class in the first world or for the cultural and economic solidarity that supported them[9].

There’s a sensitivity to threats to economic safety and social stability like rampant inequality (a leftist fear, historically not great for stability) and loss of work ethic and trust (a rightist fear, not great for stability either). For leftists and rightists these are separate things, and you worry about one more than the other, but for this quadrant the two are merged into one large sense that the social fabric is deteriorating[10].

Near the center it isn’t Sparta by any means, but considerably closer to it than, say, the political center of gravity at your average upper middle class dinner party.

•

Up is on the up

The Up quadrant is gaining in political power throughout the western world. It’s often called “populism”, but I don’t exactly want to call it that because I think the populism is incidental. It’s a contingent result of elites not taking their concerns seriously, resulting in anti-elite sentiment. In essence, they’re angry at ruling elites for not showing them the loyalty they think they’re entitled to.

This anger’s been ignored and disdained by the right and the left[11] — understandably because given any of their worldviews it’s illegitimate. From the perspective of the comparatively thrive-y left — in whose world we treat everyone with equal compassion because we can afford it — expecting such loyalty (preferential treatment, really) looks like xenophobic stinginess. From the right it looks like a demand for a sacrifice of aggregate economic growth in the name of loyalty (preferential treatment, really) that they have no right to make in the first place: “Can’t compete? Nobody’s problem but yours.”

The dismissal has backfired, to put it mildly. Britain is leaving the EU, Donald Trump is the President of the United States, France is teeming with yellow vests, and the Sweden Democrats have 62 seats in the parliament building ten minutes’ walk from this café.

These all make more sense as “up vs. down” than “left vs. right” conflicts and the left-right system isn’t well equipped to deal with that. Part of the problem is that a one-dimensional spectrum focused on left and right with liberals in the middle will result in Up being assigned a role of endpoint, obscuring its coherence and making it seem extremist and fringe even when not very far from the center in absolute terms.

•

Varieties of slicing (part 2)

To very specifically hammer at a point I want to make to Americans who consider the small-town, patriotic conservative the essence of the right: this “Up” group is not essentially left-wing or right-wing as I conceive of them. To me, the central example of a right-wing politician isn’t Donald Trump but Margaret Thatcher, and she didn’t exactly appeal to coal miners.

On which side the Ups end up depends, just like their opposites the liberals, on the particular time and place. In America I think it’s the low base level of national cohesion and long history of self-sufficiency that has made political history take a somewhat different turn compared to in Europe.

Let’s look at that compass again, now without a big hole up top. If we draw the whole line we get a division I think makes sense for the United States:

The landscape is sliced mostly along the Thrive-Survive divide, putting the top quadrant mostly on the right, emphasizing their conservative (“survive”) aspect.

In Sweden we don’t have the same strong relationship between “left vs. right” and urban vs. rural/suburban the US has[12] and the archetypical salt-of-the-Earth type working class voter who values honest work and national solidarity is, historically, not a rightist but a social democrat. This is the full slicing I’m more used to[13]:

In other words, the temperament and values often called “small-town conservatism” — in Big Five terms low openness to experience, preference for clear answers etc. — isn’t essentially right wing; it exists in considerable tension with free-market capitalism and its associated “rootless creative destruction ethos” and this aspect can sometimes dominate.

In other words, the temperament and values often called “small-town conservatism” — in Big Five terms low openness to experience, preference for clear answers etc. — isn’t essentially right wing; it exists in considerable tension with free-market capitalism and its associated “rootless creative destruction ethos” and this aspect can sometimes dominate.

The astute observer may object that I’ve simply declared the essence of left and right to be whatever is common to the left and right in Sweden and the United States. They’d be kind of right but I’m not sure it’s much of a problem, given that I think most other western countries are somewhere in between (I wouldn’t extend this model outside that group).

•

Postscript

Is this a better model than the political compass? I don’t know. The quadrants form more natural categories to me, although I recognize that people might have different opinions on that. I wrote these posts because I thought the compass was all wrong not in content but in format. It’s inside out. It has what’s to be explained as its inputs and the underlying dimensions as its outputs, possibly because we’re more used to the outputs and therefore think they’re “simpler”. I don’t think they are.

Of course I should also fess up to being highly motivated to articulate the to me very distinct difference between leftists and liberals that tend to disappear in US-dominated online discourse[14].

I’m half-regretting getting caught up in all this. Usually I try to say something newish, and this topic has been dissected and mulled over so much by so many political scientists, philosophers and bloggers that I don’t have that much to add other than some half-baked speculation of limited novelty.

Hell, my model — even the tiltedness — comes up if you look up “political spectrum” on Wikipedia.

It’s got the same quadrants but gets them using the boring “economic” and inadequate “cultural” axis I was trying to get away from. But since the resulting landscape is the same I’m not sure I’ve accomplished much.

I’ve spent far too much time writing, editing, re-editing, erasing, re-writing and re-erasing various ways to make sense of this model, when all I really wanted was to use the coupled-decoupled approach to politics I thought was neat. The thrive-survive thing wasn’t even my idea at all. I just thought it happened to perfectly complement my axis and voilà! — there was a simple model. I didn’t mean to write 8000 words on it (with another 3000 or so discarded), it just happened. “This will be easy and quick” I thought, before getting lost at the deep end of the pool looking for the best way to justify why the populist left and the populist right are more the same region of a square than the opposite ends of a spectrum[15], all without saying something obviously dumb.

A learning experience — I’d think if I didn’t I know I’ve done this before and still can’t control it.

This is followed by Variations on the Titled Political Compass.

• • •

Notes

[1]

Say, more like taxes than detailed regulations or restrictive norms regarding how selfless you’re required to be. For a personal example, I very much see the problems with drug and gambling addiction and have quite a powerful distaste for the advertising and business practices of online gambling companies, but I also very much resist having any of it banned. I would much prefer — even it if would be less efficient — using large amounts of public funds to help people escape destructive behaviors.

[2]

This is part of the reason I’m skeptical of political taxonomies based explicitly on what policies you support. As mentioned in The Signal and the Corrective, people often support similar policies for different reasons.

[3]

I saw a similar example in the wild recently. I listened to Joe Rogan’s podcast where we was talking to independent journalist Tim Pool and Twitter representatives Jack Dorsey and Vijaya Gadde. Tim commented that Joe was close to socialist politically and he answers that he’s not, but “very liberal” except for on the second amendment where he disagrees with liberals. I had to do a double take there but I understand it to mean he’s pretty consistently liberal since the left-wing position on the second amendment isn’t liberal.

[4]

The other popular choice, “centrist”, has similar issues.

[5]

Born in a city state with the necessary population density early in history

[6]

So did 1990’s liberals like Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, showing that both the Up and Down quadrants can be “centrist” on a left-right scale while having opposing visions for society

[7]

In further support I’d point out that actually existing communist societies looked pretty similar to fascist ones, despite serious ideological differences. How come? I think that can be resolved by saying that communist societies are in the far left corner in theory; to work they have to be so rich that they can adopt perfect Thrive thinking together with their extreme coupling. But when they aren’t post-scarcity they slide toward a fascist-like structure because they’re confronted with a reality that requires more of a Survive mindset than a “good” version of communism can handle. In other words, fascism is intentionally in the top corner, while communism collapses into it upon contact with scarcity.

[8]

The reason the “horseshoe” is open upwards instead of downwards is partly because of “fascism fallout” as described, partly because it tends ot be a response to threat and crisis which creates an aura of “extremeness”, and finally partly because the chattering class that disproportionally determine public discourse and collective consciousness are significantly more Down than Up, making Down a high-pressure zone as opposed to the vacuum on the other side. Note for example how the phrase “fiscal conservative, social liberal” is common in the US, meaning essentially Down (perhaps close to the right border). However, while the opposite phrase is less known, the actual position is more common.

[9]

When I wrote and rewrote this description I kept worrying that it was either too charitable or too uncharitable. I guess when I worry about both it’s probably alright

[10]

You could call the top and bottom quadrants Open and Closed, where Open is another word for liberalism and Closed for the last quadrant. I don’t intend for it to be insulting, it’s just that what it values can be reasonably summarized as such: predictability, stability, control, cohesion and balance. The Open quadrant values dynamism, difference, creative destruction and disruption, decentralization, speed and excitement — which is great fun when you’re not threatened by any of it. Both Left and Right are semi-closed and semi-open because they favor certain kinds of restrictions and not others, in the left’s case to prevent people from hogging more than their fair share of existing resources, in the right’s case to prevent people from being a drain on the prosperity creation process.

[11]

The liberal camp right across tend to engage in both criticisms plus a few measures of disbelief, confusion or pity. Personally I’ve made efforts to understand their point of view and become far less dismissive than I would’ve been, say, ten years ago when I viewed them with outright disdain. It no longer looks like either entitlement or xenophobia, but more like tragedy. I sympathize, but there’s just no way to accomplish what they want with acceptable means, or even get the desired results.

[12]

Most cities are pretty representative of the country as a whole when it comes to left and right. The most you can say is that wealthy suburbs vote more right (but not “up”) and small industrial towns and the sparsely populated north vote more left (but not “down”).

[13]

For now at least, because the Swedish political landscape is shifting as well. After several months of post-election deadlock, two liberal parties reluctantly agreed this January to leave their former coalition partners on the right to support a social democratic government in return for pro-market reforms. The rise of the Sweden Democrats necessitated the change.

[14]

For instance, I think studies about the ideological lopsidedness of US universities miss the mark when they cite the huge difference in representation between “liberals” and “conservatives”. Yes there are very few conservatives, which is an issue. The much discussed censorious PC and activism culture however, isn’t caused by that as much as by an imbalance between leftists and liberals. Such deas are, virtually by definition, pushed by the former and not the latter.

[15]

This episode of the Intellectual Explorers Podcast with Bret Weinstein has some discussion of this, referencing known right-wing pundit Tucker Carlson’s apparent embrace of some pretty far-lefty ideas.

Did you enjoy this article? Consider supporting Everything Studies on Patreon.

> I didn’t mean to write 8000 words on it (with another 3000 or so discarded), it just happened. “This will be easy and quick” I thought, before getting lost at the deep end of the pool

I feel for you, brother.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I bet you do!

LikeLike

Thanks for another great post. Very highly appreciated, at least by me.

A few thoughts.

1) It seems like the coupled/decoupled distinction applied to politics is an alternative formulation of the distinction between positive vs negative rights/liberty. Do you see these as equivalent or is there something extra coupled/decoupled is capturing(excluding)?

2)Thrive/Survive looks like a measure of (political) risk aversion which is some combination of the conservative/radical and progressive/traditionalist axes. I’m curious what if any correlation there would be between this and an individual’s levels of social and financial risk aversion.

3)I agree and identify with your description of liberalism in “I, LPC” and I agree that liberal support for say fighting poverty and other aspects of the welfare state isn’t for “coupled” reasons. However, I don’t think it has to be for “thrive reasons” The survive reason which resonates with me is to placate the losers in the free market system and the victims of bad luck because it is worth it to “protect prosperity” (capitalism and liberalism) while we still can from those potentially very angry voters.

4)The archetypal “salt of the earth” Swedish working class guy supporting Social Democrats reminds me of the description of what hardcore Trump supporters are said to want, “socialism for white people”.

5)A lot of great research on the psychology of coupled/survive voters has been done by Karen Stenner. Here is a link to a really good and very recent podcast she was on. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2019/03/authoritarian-populism-and-authoritarian-voters.html

LikeLike

I haven’t seen anyone plot the left-right fault lines the way you have before. It was a good addition to the concept.

http://www.spectator.co.uk/the-magazine/columnists/3648523/you-know-it-makes-sense.thtml is another good article on this broader idea.

LikeLike

Thanks, but I can’t get that link to work.

LikeLike

Might as well call the top quadrant ‘China’ or ‘Singapore’.

LikeLike

I did do that in a paragraph I decided to trash because I didn’t feel confident enough about it.

LikeLike

Your footnote 7 is fantastic and seems like an excellent retrodiction for your model. Yes, it predicts the same four quadrants as the Wikipedian one, but this is an extra fact that yours derives and theirs does not. Also while I am not a huge fan of the coupling/decoupling labels, the concepts you’re outlining there (a specific definition of the individualism/collectivism axis) seem like a good natural axis on which to classify things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Footnote 7 really needs to mention that what the world understands as Communism, because it is what happened to Communist regimes in reality, is actually Stalinism. Stalinism is a bastardisation of “Communism in Theory”, which is Marxism.

So yes, Marxism is at the far left of the Left quadrant, whereas Stalinism (or the Cultural Revolution in China) is pretty much overlapping Fascism – it has the same outcome as Fascism, even though the motives are different.

LikeLike

I don’t think that is true or relevant.

LikeLike

Thanks for another fantastic post. I really appreciate all the work you put into these. I have a few thoughts.

1)The coupled/decoupled axis looks to be an alternative formulation of the positive versus negative liberty/rights orientation. Do you see these as equivalent or do you think your formulation captures (or excludes) something extra?

2)The thrive/survive axis appears to represent one’s level of political risk aversion which combines risk aversion with respect to both policy and implementation. It could be represented as some kind of weighted sum of scores on conservative/radical and progressive/traditionalist (as defined in I, LPC).

3)I don’t agree with your claim that liberals support some aspects of the safety net / welfare state (your example: govt action against poverty). That is definitely true for some liberals. But how would you place a liberal (as defined in I, LPC) who supports some redistribution / welfare to placate the worst off under capitalism/liberalism in order to weaken support for far left parties? This would clearly be a “survive” motivation driven by the fear of bad (to a liberal) political outcomes in a democracy. In the U.S, people sometimes say that the new deal “saved capitalism”.

4)The strength of social democracy among working class Swedes reminds me of the charge that what Trump’s base really wants is “socialism for white people”.

5)A lot of great research on the psychology of coupled/survive voters has been done by Karen Stenner. She was recently on the following podcast which I enjoyed listening to.

https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2019/03/authoritarian-populism-and-authoritarian-voters.html

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you’re right about the positive-negative rights thing, but that’s a little too abstract and I wanted to explain it more in psychological terms, like, how it feels on the inside, and what the root of the difference is.

I’m not sure exactly how this combines with conservative-radical in the LPC sense, I think I’d define radicalism as the outer rim of the square, but shifted towards the thrive side…. if that makes sense.

I do think most liberals who *do* support such policies do it for thrive-reasons, although not everybody does — there’s considerable variation there. For those that consider freedom something to build and not as a deontological non-interference principle there is significant leeway, however. The difference between that and leftism is clear to me however because of the fact thatc while I support many pretty leftist policies I find the underlying worldview that justifies them alien when coming from the left.

Wrt that being “survive” mindset… I don’t think that should be taken too literally. I interpret thrive-survive not so much as actual fearfulness but concern for “the basics” over high-minded, distant and abstract concerns (which explains why climate change concern isn’t “survive”: it’s concern over a currently abstract, long term issue you’re more likely to consider when you don’t have immediate, personal concerns like having to work in the coal industry to support your family).

About 4)… I suspect you’re somewhat right. The issue of race in the US is probably part of the reason political alliances look a bit different than it typically does in W. Europe.

Thanks for the podcast tip, it’s in my queue.

LikeLike

Any idea why my post from March 26 didn’t show up until today? Had to rewrite the whole thing the next day, won’t submit a long comment before saving it in notepad from now on!

LikeLike

I fished it out of the spam filter. No idea why it got stuck there.

LikeLike

The first line of point 3 was supposed to be “I don’t agree with your claim…….for thrive reasons”.

LikeLike

Even though you and Wikipedia derive roughly the same quadrants, I don’t think they’re drawing the axes in the same way. You’re wondering who’s the moderate in your upper quadrant and how they’d identify, since fascism is poison. You know who your description of the quadrant makes me think of? My Evangelical Christian friend. And this made it click for me. Of COURSE I don’t associate him with fascism; the Nazis are fascist, versus my friend who believes every human is made in God’s image. But your depiction of him is spot-on. And Wikipedia’s “economic focus on community” definitely doesn’t capture the reasons he thinks what he thinks; he’s totally in a coupled-survive mindset but because of the wacky American alignment system, it winds up that he vaguely expresses support for libertarianism partly because he worries the welfare state erodes family life, devalues personal relationships, and is too bloated for our country’s (America’s) survival. To me, the upper quadrant moderate isn’t culturally Spartan, they’re culturally Evangelical.

LikeLike

This corresponds with my initial impression. I thought for sure that the punchline for the upper quadrant was going to be theocracy of some kind and was surprised by the other label.

LikeLike

Argentina’s fault lines definitely look like Sweden’s

LikeLike

When your first post came out, I was intrigued but skeptical that you could carry the topic to a compelling continuation. You delivered well!

A two axis model is far too simple in my mind to talk accurately or coherently about the positive universals and is more appropriate in establishing impossibility results or rejecting over-reaching assertions. So the most useful part of this model is the cross-comparison of the Swedish political coalitions with the ones in the United States (and the way it empowers others to do the same, as Nestor does above) and the way that the illustrate potential fault lines in each. I’d love to see a categorization of more political movements across different cultures and different times to see how well they match the model and which ones fail to neatly place (and in so failing, illustrate the assumptions of our time that go into making the model).

I’m curious how whether you would predict deterministic movement of people between quadrants in the event of some sufficiently large catastrophe (e.g. outbreak of war) and, if so, in what directions?

LikeLike

Very good criticisms of the Political Compass and its ilk. I’ve added them to my The Worlds Smallest Political Quiz index at Critiques Of Libertarianism.

My biggest complaint about your diagram is the implicit categorization of quadrants formed by 2 crossing axes. Better to have axes drawn at the sides. A person’s or ideology’s location on the diagram is better represented by a dot/cluster plot than an area. Then you can say whether you are near or far from some orientation.

I have a few hundred lines of notes on other political classification axes, schemes, and ideas if anybody is interested. Email me.

LikeLike

There are significant views that are excluded from your graph. For example, where does Catholic Social Teaching fit in?

On the one hand, it requires certain “thrive values,” as you call them: generosity, respect and care for the weak. CST also promotes a universal love for all people, echoing the teaching of the parable of the Good Samaritan and several other parables from the Gospels, and is profoundly opposed to the sort of “survive values” that limit our regard to only some close kin.

It also explicitly condemns the acquisition and maintenance of wealth and material riches for the sake of pleasure or personal advancement; the sort of economy that exists today is, in many ways, abhorrent from the point of view of CST. So it must have in mind, in its idea of “thriving” and what its preconditions are, something quite different from the liberal vision of the market economy. But this tracks fairly well with what you said about “coupled” socialist states. So far, then, you might think it fits well into the “left communitarian” category.

Its idea of thriving incorporates ideas you would put under the heading of “survive values.” A thriving society is peaceful and just. The peace is created and maintained by a well-functioning hierarchy in which people perform their social roles and obey the legitimate those with authority over them. Justice is also partly constituted in terms of that hierarchy, along with the dictates of practical reason. In a peaceful and just society, according to CST, people make sacrifices for others and for the social wholes of which they form a part. Practical reason is not simply a matter of the fulfillment of desires, and so they sometimes have to ignore or untrain their desires. Again, here you might think CST fits neatly into the “right communitarian” category.

I hope you see the problem. The concepts you’ve used to try to define the axes are thoroughly liberal: they are a liberal’s way of understanding what is at stake in political discourse, and what it means to have a good life or society. There are other conceptions of what is at stake and what is good which cut across the distinctions made by the liberal account. Political disagreement happens at multiple levels. There is disagreement over what the issues are, how the issues are to be characterised, and what counts as a solution, among other things.

LikeLike

This is a great follow-up to part 1. In particular, I agree with PDV, above, that footnote 7 is a valuable retrodiction.

I don’t understand footnote 5, which currently reads, “Born in a city state with the necessary population density early in history.” That sort of sounds like a note-to-self about what you intended to write, but maybe I am just being obtuse.

LikeLike

“the archetypical salt-of-the-Earth type working class voter who values honest work and national solidarity is, historically, not a rightist but a social democrat.”

I’m an American rather than a Swede, and I’m confused by the statement I’ve quoted above. “Social Democrat” to me means, someone who is in favor of Socialism, but is also in favor of Democracy, ie, someone who wants to achieve socialism by democratic methods, ie, is more committed to democracy than to socialism. Is that what social democrat means in Sweden, too? If it is, my mind is boggling, because I don’t see how someone who is in favor of socialism can also be someone who ‘values honest work’. Those seem like polar opposites to me. Could you expand or clarify this statement a bit more for us Americans?

LikeLike

Ah, here’s the answer to my question, as to what the Swedish definition of ‘socialism’ is, over in your post “Anatomy of Racism”:

“…someone supporting high taxes and a generous social safety net but not an end to private capital ownership to call themselves a socialist…”

I can see how someone can have that definition of ‘socialism’ and also value hard work.

But to me a generous social safety net isn’t socialism at all. To me, socialism is: ‘from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs’, with ‘the state’ or rather, the people in control of the state deciding, arbitrarily, what are the ‘needs’ and the ‘abilities’ of each. Which of course, due to human nature, always results in a pretty ugly outcome, since absolute power corrupts absolutely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

European social democracy has historically been closely tied to unions and the labor movement, with the chief concern being the fruits of labor going to the laborers over capital owners. “Honest work” is in opposition to ownership, management, middlemen etc. capturing value. “Free stuff for the idle” hasn’t been the focus and the more responsible ones realize that keeping the population working is imperative.

LikeLike

A better term for “socialism by democratic methods” is democratic socialism. Though no label is perfect: Bernie Sanders called himself a democratic socialist but his policies are those of a social democrat reformer, not someone wanting to (democratically) seize the means of production.

That said, there’s no conflict between favoring socialism and valuing honest work. The core ideas of socialism are worker control of the means of production, or not having to work for wages for a private boss — not having to pay rent for sheer access to land and capital. An economy composed of the self-employed and worker-owned cooperatives would be compatible with (market) socialism, and full of ‘honest’ workers.

LikeLike

“From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” is the principle of distribution in full communism. The socialist version is “to each according to his contribution.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/To_each_according_to_his_contribution

LikeLike

Oh dear — this was meant to be in reply to dlr, above.

LikeLike

I disagree with equating “decoupled” with the right-wing: Burkean conservatism is a very “coupled” ideology (and mainland European counter-revolutionary thought, like Bonald, even more).

LikeLike

Yes and no… I think at least part of that is adressed in the clarification in the beginning.

LikeLike

Personally, I think the essence of the political decoupling/coupling can be more clearly understood as: “decouplers” expect relations to “strangers” to work like homo economicus bargaining, with each agent keeping their utility function unchanged; whereas “couplers” expect relations to work like AIs doing acausal trading, with each agent modifying its utility function toward that of the other. In other words, decouplers expect each party to pay attention (only) to their own interest during the bargaining, while couplers expect that both parties will mutually act as agents to the other party (as principal). To an extreme decoupler, Alice mildly confusing Bob and getting him to make a contract contrary to his interest is just Bob being an idiot, Alice didn’t violate her moral duty because she didn’t have any.

The Platonic ideal decoupler transaction is the cafeteria: one party posts its indifference curve publicly, the other party finds the (from its PoV) best deal on it. The Platonic ideal coupler transaction is where the two parties sit down, explain their desires to each other, and then work to find a solution to best satisfy the union of those desires.

LikeLike

Yes, something like that. I don’t know if the decoupling concept is the best way to describe this, because I think it’s very much about empathizing-vs-systemizing thinking as well. I do think a good way to hammer point out the difference is whether or not you have a duty to actively empathize to explore and pay attention to other people’s utility functions. For close friends and family most agree yes, but for everyone else there’s a great deal of confusion and instability. It’s impossible to do it with everyone all the time, but when and who? If I see a picture of a starving child, does that assign certain duties to me? What about compared to another such child I don’t see? It’s a mess. I’ve been thinking about writing about it but I haven’t found the right way yet.

LikeLike

Wouldn’t the top quadrant just be totalitarianism generally (with all its myriad forms)?

LikeLike

Not really, that’s by its very nature extreme and considers every facet of life to be part of the political realm. I’d say it’s the whole line at maximum coupling.

LikeLike

If you are struggling for a name for the Up quadrant, then I would suggest Monoculturalism.

Because having met a few people like this, they are very, VERY focused on ingroups and outgroups (they don’t know they are, but that is what any psychologist would be able to spot).

This focus on social/cutural cohesion means they have a very restrictive/reductive idea of who is in their ingroup. A very “Us and Them” mentality, where “Us” is a really narrow defined set.

So I suggest Monoculturalism because anyone with even a slight cutural difference is “Them”.

In the UK (actually in England) these people are known as “Little Englanders”, mainly because their world view is so small. Not only do they feel pride that Great Britain is an island (and therefore has a natural physical barrier keeping “Them” out), they are also in a permanent state of “siege mentality” – very much Survive mode.

And they voted for Brexit in vast numbers.

LikeLike

I know i am late to the party, but this is my best understanding of what the upper quadrant is. Fascism without the negative connotation is a good name, but i think even better is monarchy. A good king loves, and is responsible for his people. I think this fits the feel of the upper quadrant the best, a king taking care of his family. As an American and a monarchist i feel it’s a super underrepresented quadrant thats liable to get you canceled. But ideally i think it is the best system.

LikeLike

A recent thought: two “trust” axes (in the mould of thrive/survive) give almost the same model.

“Ordinary” thrive/survive becomes a somewhat poetic “trust in the world” (“mistakes are mostly survivable, you get to try again” vs. “some mistakes are deadly or permanently crippling, and even if everything lost can be regained, doing it eats opportunity cost—we don’t call it a ‘mistake’ if it doesn’t!”). Decoupling becomes “trust in people”.

Actual liberals both trust the world and people. Hence their support for ideas like UBI: yes, some will spend it on booze, but mostly people can be trusted to know what they want, and would use it well.

Rightism as used above resembles e.g. a disaster response: nature is unforgiving, while a human face is a friendly face; people help each other, each in their own way, because that is the natural human thing to do, not because they are compelled. (An excellent description of this sentiment is https://srconstantin.wordpress.com/2017/05/30/the-face-of-the-ice/).

Leftism trusts the world but not people. It has a one-size-had-better-fit-all lifestyle (“respectable” middle class) that is to be imposed on everyone; hence the proposals like public food (https://slatestarcodex.com/2017/11/21/contra-robinson-on-public-food/) and general love of lifestyle regulations (American zoning laws being a particularly egregious example). People cannot be trusted to “do their own thing”, the threat of some punishment (from social disapproval to more severe ones) is needed to keep people in line. American leftists wage endless flamewars on each other in the course of negotiating where to draw the sharp boundary between what is “respectable” and thus must be accommodated, versus what can be forgotten/dismissed/discriminated against.

Up-ism doesn’t trust the world, and sees people as adversarial-by-default, requiring strong norms (“fabric of society”). Large changes are doubly threatening, both by their direct impact, and perhaps more importantly, because they can break parts of the fragile social order. People are also uncomfortable if it is unclear what the norms are, because they might unwittingly violate them, and this mistake can have severe/irreversible consequences (ostracism, “social death”).

LikeLiked by 1 person