My last post on Tom Chivers’s book The AI Does Not Hate You took an embarrassing amount of time and work to get done. My posts on books tend to, because I jot down a lot of thoughts when reading and then I have a hot mess to take care of, which I put off forever. Many such thoughts overlap a little bit, some are interesting but tangential, and some work together but point in different directions and thus become difficult to put in sequence in a way that feels natural.

Let’s say my notes after The AI Does Not Hate You looked something like this:

Not a nice straight line. A bunch of dots, some larger than others, to be connected somehow. I spent a lot of time and effort trying out different ways to arrange them. Most weren’t particularly elegant.

Several awkward twists and turns.

Even worse somehow.

The phrase “kill your darlings” applies. Sometimes that one part you love so much ruins the flow of the piece and you have to get rid of it for the rest to work. For me there’s also the problem that, while I often complain about not being productive enough I also often end up writing way too much[1]. Getting the review post down to a reasonable length required some savagery. In the end it came out something like this:

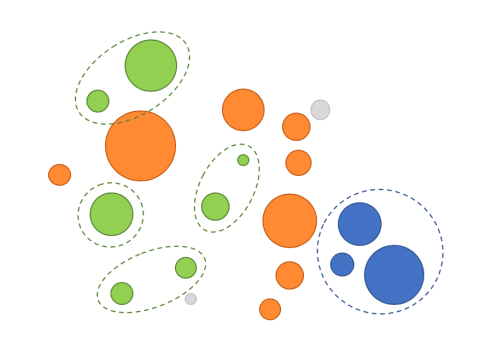

There’s quite a lot left here, after the main narrative had been removed. This post is me picking up those leftovers and throwing them into the frying pan in the hope of a decent meal. Besides the main story in the last post (orange, below), some stuff just got thrown into the trash (light gray), something else got big enough to be put into its own, forthcoming, post (blue), and the rest (green) is here.

It probably makes sense to read the main piece first, unless you already have.

•

The art of the mind dump

The first tangent is relevant to the intro. It’s on Chivers’ explanation of why rationalist movement founder Eliezer Yudkowsky wrote many hundreds of thousands of words on his view of what rational thinking is just because he wanted people to understand exactly why he thinks what he thinks about artificial intelligence:

So in order to explain AI, he found he had to explain thought itself, and why human thought wasn’t particularly representative of good thought. So he found he had to explain human thought–all its biases and systematic errors, all its self-delusions and predictable mistakes; he’d found a natural home on Overcoming Bias. And to explain human thought, he found he had to explain–everything, really. It was like when you pull on a loose thread and end up unravelling your entire favourite jumper.

Personally I appreciated this “omni-philosophy” aspect of Yudkowsky’s writing much more than the specific conclusion he wanted to get to. The “this is my whole worldview” genre is fascinating. You get to look straight into the mind of another person and see how things hang together in there.

I very much understand why he felt the need to do what he did, because I have the same feeling. In my case explaining my entire worldview feels necessary for really, truly, communicating why I think what I think, not about AI, but disagreement.

I kind of want everyone to do this. If we had to read a hundred thousand words of somebody’s philosophizing before feeling confident that we understand their point of view, the quality of communication on complex topics would greatly improve. Sadly it’s ridiculous, so the closest serious exhortation along those lines I’ve done is 30 Fundamentals.

Writing these mind dumps is a lot easier if you’re like Yudkowsky and can, seemingly, write down your thoughts as you’re thinking them and have it come out making sense. I’ve heard the other major rationalist writer Scott Alexander say that he just writes what he’s thinking and doesn’t quite understand why people say writing is so hard. I’m unbelievably envious. For most of us, pulling on a thread and actually winding up with a thread instead of a curled-up monster takes a lot of hard work. I tried to go free-wheeling last year and I didn’t particularly like the result.

•

From weirdness to badness

There’s a part of The AI Does Not Hate You when Chivers discusses how the weirdness of the rationalist community puts people off. The cuddling and widespread polyamory leads to accusations of being a sex cult, and I understand how you can come to that conclusion if you take a particularly leering look at the whole thing. According to the book, a Reddit community dedicated to mocking the rationalists “latched on with enourmous glee” to an old OKCupid profile Eliezer Yudkowsky had put up, where he was (as he often tends to be) self-aggrandizing, very open about his personal fetishes, and displaying an open, straightforward attitude to sex. Chivers talks about his own reaction to it:

It gives me an icky sensation, but again, it’s just a bit weird, not wrong, at least as far as my moral framework goes. If women want to message him, great; I hope it works out for all parties. But for some people the ‘ick’ factor is stronger, I think. I’ve heard it described as Yudkowsky ‘trawling for sex’, but I can’t see how you get there. He’s just openly stating that he wants sex and that if anyone wants it with him they should ask.

I saved this quote because I think it’s important. We all have “ick” impulses. That’s fine, it’s part of being human. But I very much object to treating your ick-reactions as valid moral judgments. There’s a lot of history of people doing that, and the vast majority of it abhorrent from the viewpoint of contemporary morality[2].

Chivers also notes this weird-to-immoral mental slide:

I don’t think the Rationalist community is a sex cult. But people on the outside, those of us like me in our hetero-monogamous, married-and-settled-down, two-kids-and-a-people-carrier world, find their whole thing deeply weird, and for us it is very hard to separate ‘weird’ from ‘immoral’.

I guess this is a personality thing, because I don’t think I have this impulse. I do notice weirdness (well, most of it) of course, but I feel no particular pull to translate it into derision or moral condemnation. The exception is when weirdness comes off as inauthentic or performative. I do judge that, but not because weirdness is upsetting as such. I just find such behavior immature, uninteresting and tiresome. I get no sense at all, from any part of the rationalist community, that their weirdness is a performance.

One of my favorite things about the community is its full-throated acceptance of by-standards-of-social-normality weirdness. It is understood and accepted that just because an idea is unusual, socially undesirable, or held by off-putting people, it does not mean that it’s wrong.

Jacob Falcovich of Putanumonit tells this story:

I told my coworker that when I’m in a rush and need a measured dose of caffeine I just chew on a handful of roasted espresso beans. The taste is not actually bad — if you like chocolate covered beans, you may not totally need the chocolate. I suggested to my coworker that she try it at least once, just to know what it tastes and feels like.

She adamantly refused, citing “that’s not how it’s consumed” and “it’s weird, people don’t do that” as her main objections. I countered that these are facts about people, rather than facts about coffee beans. While you can infer some things about beans from observing people, the beans are right there in the office kitchen to be experienced directly. My coworker seemed unable to grasp the distinction, treating the social unacceptability of eating coffee beans as akin to physical impossibility.

I know I shouldn’t judge this person, but I have to summon a surprising amount of mental generosity to avoid it. I guess I carry some resentment towards “weirdphobia”. And I’m not even that weird! I live a very conventional life, with a wife and 2.1 children, two sensible cars, a mortgage, a conservative wardrobe and a job with a lot of powerpoints. My gut just hates that attitude for some reason. Part of me sometimes want to grab people[3] and say no this isn’t weird, you are weird! You just don’t know it, because the rest of humanity is sharing, enabling and validating that weirdness!

We humans are all weird. We’re packed to the brim with unexamined assumptions and black-box concepts that don’t make sense when we look into them, but we’re nonetheless convinced they’re well supported and in no need of explanantion. And we react negatively to people challenging, questioning, or just not sharing them.

Weirdness and politics

When we enter politics this gets a lot worse. Wooo-boy. Here “is true/makes sense” is conflated with “is socially accepted/desirable” all the time like everywhere else, but the stakes are extra high.

Weirdness, in the sense that describes the rationalists, means being very aware of this disconnect. One consequence is that they accept an unusually wide range of political beliefs. In The AI Does Not Hate You, Chivers tries to deal with this, but it’s far from the book’s strongest part. I think he shies away from really putting the spotlight on the aforementioned disconnect, and without that I don’t think you can explain the rationalist attitude to political discussion and debate very well.

There are two chapters on politics, specifically about feminism and the neoreactionaries. I believe Chivers is aware he needs to discuss them but doesn’t quite want to and aims to keep it as short as possible. I understand why. If given anything more than the bare minimum, they could easily swell up to overshadow the whole rest of the book and that wouldn’t be good for anyone. I might have done the same thing myself if I wanted the parts about AI and existential risk to take center stage.

In the review I wrote a bit about the problems with the feminism chapter and I could write a lot more, but I’ll save that for another post. I’ll just mention how it ties into the disconnect described earlier: feminism, insofar as it is a complete ideology like conservatism, liberalism, communism, capitalism, anarchism etc. has a lot of weaknesses and blind spots (as all ideologies do). However, in polite society those weaknesses aren’t pointed out as much and as clearly as they could be. Dissent exists, sure, but it’s mostly expressed as silence, lack of interest or total but superficial rejection, not detailed criticism. It’s seen as attacking women, which is very bad form, according to both feminism and to traditional gender norms.

Exploiting this norm protects ideological feminism from intellectual criticism from everyone with social capital to safeguard through exactly that thing that makes people confuse “is socially accepted” with “is true/makes sense”. “Weirdos” don’t see such norms as sharply, and are more likely to object to things that don’t make sense to them.

In short, the conflict isn’t the contingent result of some particular event. It’s inherent, because curious, intelligent weirdoes are the natural enemies of belief structures that rely on social acceptability to not get criticized.

And the neo-who?

Rationalists’ acceptance of weirdness can push them in all kinds of political directions. Some follow their compassion towards an extreme concern about suffering that go beyond everyday charity giving, Effective Altruism or veganism into asking whether fundamental particles can suffer. A few other affiliated people have gone in the other direction, like the neoreactionaries.

I don’t know a lot about them. As far as I know they’re a tiny fringe group who want to abolish democracy, roll back cultural modernity and return to a sort of feudal/monarchic politics. They embrace hierarchy and readily incorporate innate inequalities into their political vision.

Something about Chivers’ discussion of them bothered me. They’re extreme, sure, but there are milder, softer versions of some of their beliefs that are more reasonable. They have some valid criticisms of contemporary society the same way communists and anarchists do. I got the feeling that he uses this very small group as a scapegoat, as a tool to explain away any beliefs disproportionately accepted among rationalists but sits uncomfortably with center-left-polite-society norms, such as the importance and high heritability of intelligence, skepticism against victimhood narratives, etc. That is, he makes the rationalists more palatable to the polite society he’s speaking to by suggesting that the relatively larger presence of such beliefs is only because of a small number of unusually talkative assholes. It therefore doesn’t suggest that very same polite society is genuinely and importantly different from the rationalists in ways they ought to examine, for example in confusing social acceptability with correctness.

Sure, I get it, but it feels ever so slightly cowardly. He does explain that rationalists take almost all beliefs as worth seriously engaging with, even bad ones. But in my interpretation he doesn’t reject the implication that they’re just humoring people as a pastime or temperamental quirk, instead of seriously doing what everyone else should be seriously doing as well. Fair or not, it seems to me that Chivers excuses this behavior more than he defends it, which I honestly think it deserves.

My life in conservatism-free society

I probably need to go into some personal background to explain why this feels important to me, and why I carry just a bit of a grudge against what I called “center-left polite society”.

To begin: I consider the political left and right wings to be on roughly equal footing, morally and intellectually. They’re both partial narratives that each capture different aspects of the physical and moral universes. Together they form something better than apart, and any cultural milieu that one of them dominates too forcefully invariably deteriorates, like a muscle that faces no resistance. I don’t think this is sufficiently appreciated in much of intellectual culture, where merely calling something “right wing” constitutes an accusation.

The society in which I grew up was almost entirely conservatism-free. The political right in this country never really pushed any genuinely conservative argumentation that I can remember; what emerged from its collective mouth is better described as neoliberal. Deregulation. Lower taxes. Actual conservatism was something you’d see on TV from the United States, and it was weird and alien, proof of how crazy they were over there and what an exotic society they had.

As I understood the world when I grew up and throughout early adulthood, conservatism was nothing but another word for anti-intellectualism, blind stubbornness and wild irrationality. I was over 30 years old the first time I came across an article that made conservative points in a reflective, rational, and intelligent manner. It felt very strange.

I’m much more used to it now. Has it made me a conservative? No, it has not — not unless you use it to mean just “non-radical”, but that I always were — but it has convinced me that conservative views has to be respected and engaged with. Say, given about 20-30% credence, as opposed to the current -50% (actively derided). The thoughtless smugness that thinks of itself as enlightenment that I used to find normal and obvious when I was younger now bothers me. As a result, the center of my political philosophy now is that we shouldn’t feel too confident in the correctness of our opinions.

The compulsive balancer

During this coronavirus crisis me and the wife both work from home, and we discuss the pandemic a lot. She’s very anti-lockdown, and opposed to almost all restrictions other than keeping retirement homes protected. I’m sympathetic to her points but much more unsure, and it drives her nuts that I keep trying to (repeatedly, she doesn’t listen) explain the reasoning of the pro-lockdown side instead of just agreeing with her. “Just tell me your own opinon, not what anyone else says!” she asks, not unreasonably. But I don’t have a strong opinion on virus mitigation strategy to give her. There are too many unknowns. I do have a strong opinon on how people express their opinions. When people overconfidently dismiss opposing arguments as nonsensical and irrational, and I know they aren’t, I want to push back, no matter what I personally think. That we should be balanced and understand opposing views is what I personally think.

It is for this reason I tend to feel protective of conservatism (for example, see here). I get irritated when it doesn’t get a fair hearing among intelligent, thoughtful people, because I expect more from them.

There’s an illustrative passage in The AI Does Not Hate You. In defending the rationalists against the accusation (sic) of being right-wing, Chivers points out that many of them spoke out against Trump. That’s true, and [BEGIN INCANTATION] I don’t like him nor would I vote for him or someone like him [END INCANTATION], but I also don’t like that I feel obligated to say so. I don’t like that it often goes without saying that supporting either him or Brexit or whatever it may be makes people wrong and bad by default and therefore what they say can simply be dismissed without examination. There’s just… enough of that in the world already. Take other people seriously. Very few are wrong about everything[4]. And even when somebody expresses a dumb idea, and God knows many do, there’s often a smarter version worth taking seriously.

•

Can you actually reason yourself into changing?

The “I must save the world” impulse that Eliezer Yudkowsky seems to have, and has had for his whole adult life according to The AI Does Not Hate You, is odd to me. The thinking is on full display in his epic fanfic Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality, where Harry also feels obligated to take the world’s problems on his shoulders[5]. And sure, I understand it perfectly well on an abstract, logical level. I just don’t and can’t share this moral urgency about all the suffering in the world and the dangers humanity faces in the future, no matter how sound the argument might be. I have just enough of that normal human capacity to push it all out of my mind.

I get how frustrating it must be to Yudkowsky and others to encounter this all the time, it’s probably the source of that “everyone is insane but me” sense I’ve sometimes gotten from him. He’s right and we are, in a way, as I’ve said.

But this insanity can be protective. Most of us fear trusting our abstract reasoning when it takes us to strange places, and that’s often a wise impulse: hubris is a staple of literature for a good reason. Trusting your own thinking over tradition has probably been a bad idea throughout history when the knowledge available to reason from has been patchy and mistakes frequently lethal. I probably have less of this self-distrust than most people do, but Yudkowsky appears to have little to none.

Perhaps his sense of urgency is reinforced by the actions it suggests. If a line of moral reasoning suggested that I must dedicate my life to tasting every flavor of ice cream in the world, that would probably make it easier for me to accept than if it suggested that I should work around the clock at a job I hate and donate all my earnings to charity. According to Yudkowsky’s reasoning, he and many who agree with him have important and interesting things to do in saving the world. Chivers says:

At the risk of overgeneralising, the computer science majors have convinced each other that the best way to save the world is to do computer science research.

I don’t mean to call Yudkowsky dishonest. I don’t think he is. But it’s also true that his conviction that AI alignment is the most important thing ever enables him to work with stuff he likes and is good at. That’s not the case for me, and that’s likely part of the reason I can’t think of it as the most important thing in the world the way he does.

The other option is that some people really can reason themselves into changing their priorities on a deep level[6]. I have a friend somewhat like that. If he convinces himself that something is the rational or morally correct thing to do, he does it, whether it’s subsisting on nothing but carrots and Brie, moving over 1000 km to the municipality with the lowest tax rate or travel around the world on boats and trains because flying hurts the environment. He lacks the “wait, no that’s crazy” module most people have. Half of me admire him and the other half is a little freaked out.

I should use that freaked-out feeling. I should use it to model how normal people must think of rationalist-type weirdoes. Perhaps it even explains the weird-to-immoral slide: people like this are unpredictable and cannot necessarily be trusted to follow convention and do what is expected of them, which easily translates to “cannot be trusted” in general.

We ought to look for opportunities to use our feelings towards X to understand how others feel about Y more often. Call it an “empathy pump”.

•

The selective conservatism of Star Trek

In the review I talked about how I’ve become uncomfortable with speculation about the far future. Isn’t that a little strange for someone who likes science fiction, as I always have? I think the key point is that most science fiction avoids doing away with recognizeable human beings, for obvious reasons. A real future where that happens is a whole different ballgame.

Case in point: Anyone who’s read a lot of this blog will know from the occasional reference that I’m a Star Trek fan. And Star Trek is, for all its mundane political progressiveness, distinctly conservative about humanity. It rejects both genetic engineering and technological mind-altering. And while it embraces very limited artificial intelligence it’s carefully portrayed as not being massively transformative.

Star Trek has fantastical technologies but leaves us humans remarkably intact — and notably always in charge of our own destiny. In fact, our self-determination is a central theme across the franchise. The original series in particular, on several occasions, comes out decidedly against things like friendly AI and the whole idea of us being taken care of by superior beings, as if we were children or pets[7].

Star Trek can even be called human-chauvinist: humans are special. We’re special because of our versatility, capacity for self-improvement and exploratory spirit. It preaches acceptance of others, certainly, but only to a point — you’re still expected to fit in. It has a staple of characters who strive to grow by becoming more human-like, instead of cultivating their difference and possible superiority. Yes, Star Trek portrays a bright future, but that’s only because it avoids future shock by populating it with people like ourselves.

•

AI — the spaceflight of the 2020’s

Star Trek’s vision of the future originates in the 1960’s and seems odd and quaint today, given how technological development has progressed. Computing, information and communication technology is ahead of what was imagined back then, but our progress in spacefaring has been anemic compared to the expectations of two generations ago. Just look at the 2001 movie — that kind of capability was supposed to be 20 years out of date now.

From my future-shocked perspective this actually offers some hope. Spaceflight was all the rage in the 1960’s because we made great strides then, but it turns out that the higher-hanging fruit is quite a lot higher up than we first thought. We won’t be building a starship Enterprise any time soon, or ever, for so many technological, practical and economic reasons. AI is similarly all the rage right now because we’re in the middle of making big advances. Will that slow down too? Is imagining a future full of AI the contemporary equivalent of imagining a future full of starships in the 1960:s?

Maybe. Maybe strong AI:s are theoretically possible, but we find out that the problems are similar to the problems with spaceships: it’s going to be completely impractical, pointless and uneconomical to build and use them. So we don’t. Instead we use an army of mundane, specialized and limited AI:s.

I feel like a party pooper but it might be the outcome I prefer, if I’m honest with myself. Sorry, visionaries.

• • •

Notes

[1]

That’s how two simple-seeming ideas turned into an 11000-word treatise on what racism is and an 8000-word two-parter about the political compass (part 1, part 2).

[2]

And if I understand things correctly, the particular anti-rationalist community in question is mostly on the political left, which means that they, especially, should be above this sort of thing, given its history.

[3]

By that I mean “people” in the abstract, not specific people.

[4]

I make absolutely no claim that the right wing doesn’t do the same sort of thing. They definitely do. It’s just a lot easier to ignore them. They don’t have the same cultural power, dominant position in the well-connected intelligentsia, and presence in the social class in which I exist. Put me in a different cultural context though, and I may well come out with some very different pet peeves.

[5]

This thinking also comes through in some of Scott Alexander’s writing, especially the Comet King character in Unsong.

[6]

I have changed my mind on things over the years of course, but typically not by formal reasoning. It’s mostly a matter of, for one reason or another, starting to see the world from a different perspective and reinterpreting past knowledge and experiences. It doesn’t feel self-directed nor logical exactly.

[7]

Isaac Asimov’s robot novels that leads into the Foundation stories shows a similar sensibility by having us reject life extension and dependence on robots because it undermines our human spirit.

Did you enjoy this article? Consider supporting Everything Studies on Patreon.

Re: worldsaving impulses and fiction, I think it’s notable that the Comet King isn’t the main character of Unsong. Scott is fascinated by, and sometimes admires, those who are trying to move mountains and save the world; but despite the very real cultural power he wields, he can’t imagine himself achieving meaningful larger things with it.

This is different from you in that Scott can feel the stakes passionately, he just thinks of himself as inexorably a side character who would be ridiculous if he attempted an active role in the fight. Like the paragraph about Hamlet in Prufrock.

LikeLike

I don’t know, I remember noticing that the comet king becomes a much more central character in unsong than you expect in the beginning, and I do think Scott is haunted with thoughts about the suffering in the world sometimes (I particularly remember a post about ‘bottomless pits of suffering’ or something). But you’re probably right that it isn’t enough to lead to much action. For me it feels obvious that you can’t think like that at all ’cause you’d be completely mentally destroyed.

LikeLike

> I do think Scott is haunted with thoughts about the suffering in the world sometimes

That’s what I was saying above. But the point is that Scott doesn’t think he’s personally capable of helping, so he just blogs about things he things are important, and hopes that other people will do the helping. (Which ignores the fact that his writing has been one of the most effective worldsaving things out there! But I think he has a mental block around recognizing that.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

enjoyed the leftovers format, think it is worthwhile. i’d be interested in reading more of these among the longer-form posts (which are great as well).

“I do have a strong opinon on how people express their opinions. When people are overconfident and dismiss opposing arguments as nonsensical and irrational, and I know they aren’t, I want to push back, no matter what I personally think. That we should be balanced and understand opposing views is what I personally think.

It is for this reason I tend to feel protective of conservatism (for example, see here). I get irritated when it doesn’t get a fair hearing among intelligent, thoughtful people, because I expect more from them.”

this resonates with me, it’s something I gravitate to doing as well. have to actively rein this in irl, since people tend to take *any* pushback on certain center-left dogma (in American politics terms) as like 5% “words pointing to concepts” and 95% “act of aggression from someone wearing the flag of the enemy tribe.”

chivers is relatively level-one-politics on twitter, so i’m disappointed but not surprised that he doesn’t seem to have fully grasped why the rationalist community is a natural home to and defender of unconventional behaviors/behavior and how tied up that is in the community’s strengths.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That resonated with me as well. See also: why I’m annoyed by the recent popularization of the phrase “The devil already has enough advocates, thanks” as a way to sniffily shut down people on forums who are making an unpopular argument or trying to reconstruct why someone acted the way they did, or anything along those lines.

LikeLike

In case you don’t already think this, I think this post is great, even if it’s just a ‘list of notes’. I don’t mind reading long texts/posts by people that write well (and I include you in that set) so I think all of this would have been perfectly fine in the previous review post.

> **I do have a strong opinon on how people express their opinions.** When people are overconfident and dismiss opposing arguments as nonsensical and irrational, and I know they aren’t, I want to push back, no matter what I personally think. That we should be balanced and understand opposing views _is_ what I personally think.

I also am like this. I’ve found most people _hate_ it, tho there’s a few that recognize it and merely dislike it. A much smaller number of people I know actively appreciate it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I have to say, despite not having read The AI Does Not Hate You or properly remembering your first review (if indeed I got around to reading it through at all; my blog-following habits have been spotty lately), I was able to enjoy this essay, and honestly it doesn’t feel that disconnected or leftovers-ish.

As someone who grew up in the US knowing lots of American-style conservatives, it’s certainly interesting to hear from the point of view of someone who was introduced to conservatism as an American phenomenon from outside the US. My feeling is still that American conservatism in the mid-00’s (at the height of the Bush era and during my politically formative years) was decidedly anti-intellectual, not on the object level of policy (which did deserve to be considered with an open mind) but on a more meta level of how to talk about policy. Nowadays it looks like a different story where the American Left has developed its own strains of anti-intellectualism while the American Right has been taken over by a faction that has flown off the rails of the rational discourse track entirely. But I digress. None of this is to say that policy positions and the overarching philosophies of each side determining them don’t deserve a fair hearing.

I particularly liked your point in your “compulsive balancer” section, as I have a longstanding frustration with how hard it is to get through to people that when I explain the arguments against their belief I’m just trying to point to what’s “out there”, not saying that I stand by those opposing arguments. And that I repeat the opposing arguments in another conversation, it’s because I’m frustrated that they were not at all engaged with the first time, not that the other party didn’t agree with them. And I too get frustrated with feeling forced to specify a definite stance of my own on a difficult and contentious topic. But some of that frustration is with myself out of a feeling that I should be capable of sifting through the facts and come up with an answer I can confidently stand by rather than only being able to steelman the beliefs of each side, while I still hold that it’s better to only know how to steelman each side’s arguments rather than to insist on coming up with my own view without caring to openly consider each side’s arguments. These kinds of personal conflicts give me the impression of exposing a significant deep-lying difference between how I think and how they think.

LikeLike

> But some of that frustration is with myself out of a feeling that I should be capable of sifting through the facts and come up with an answer I can confidently stand by rather than only being able to steelman the beliefs of each side, while I still hold that it’s better to only know how to steelman each side’s arguments rather than to insist on coming up with my own view without caring to openly consider each side’s arguments.

I’ve come to accept that the ‘right answer’ might in fact NOT be one that I hold confidently, or that my uncertainty might be so large as to preclude me from having a definite answer at all.

With regards to politics specifically, I’m leaning towards the ‘answer’ that, given the immense complexity of human values, and the vastly heterogeneous distribution of possible values among people, a lot of disagreement is fundamentally aesthetic, i.e. due to different _preferences_. For example, I don’t think of Amish ‘politics’ as being fundamentally ‘incorrect’ – just (mostly) the result of different preferences (and regardless of their particular justifications).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes I think you’re right about the differences between the ’00s and today. It’s not just me who’ve changed, it’s the discourse too, and the anti-realist approach to public debate that was mostly at home with the Bush-ist right then can be found across the political spectrum now. It leaves very little for the rest of us.

It’s not strange to expect others to have a definite opinion on issues if we see the primary purpose of opinions as driving action. Sharing them with each other is a way to coordinate for collective action, and those of us who refuse to play that game are frustrating. To speculate, it might be that some of us are better suited to working alone than in groups and have the psychology and epistemology to match.

LikeLike

“_he just writes what he’s thinking and doesn’t quite understand why people say writing is so hard. I’m unbelievably envious_”

Especially given your interest in disagreement, I wonder whether your experience is like mine when writing: the first draft comes across like two or more persons arguing.

LikeLike

I feel like this sometimes, at least for me, is an entirely accurate depiction of my views! I often describe myself as being ‘of many minds’ (i.e. a more general form of ‘of two minds’) as different _parts_ of me feel like they have or lean towards different conclusions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not really. I’ve had ideas to write several posts in dialogue form but I’ve never completed one.

My drafts tend to drift off and lose focus as I bring in more and more ideas that I think are related and should be included as well, until it all becomes unwieldy and the associations are not strong enough to stand without qualification or discussion of objections, so I add that too and then it gets complicated and I develop an “ugh” field around it — or I do all this second guessing inside my head and then never even write it down because it doesn’t feel any good.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have you perused EY’s Inadequate Equilibria? It’s in paperback and blogform, an interesting look at how he handles hubris vs. modesty, self-doubt, and the problem generally of when to trust an existing system of solving problems vs. go his own way. Far from a perfect book, but useful for folks like us (who are attempting to create alternative discourses, an act which carries its own hubris) and also as a psychological look into Eliezer.

LikeLike

I haven’t. I’ve read Scotts review of it and it felt enough, but maybe it’s worth reading in full anyway — after all the other books I want to read first:)

LikeLike

Yes, I think that might be enough!

Do you think we’ll ever get a piece reconciling the rationalist Double Crux method with erisology? It seems like a fair number of LW community members have really been thinking and pushing dispute resolution, led in part by Julia Galef (I’d imagine inspired in part by this blog… in implementation even if not in origin…). But I’d be curious to get your thoughts on the method & its relationship to some of your ideas here

LikeLike

I’m bad at remembering and reiterating it, but “erisology” is supposed to be an umbrella term referring to all knowledge and ideas relevant to disagreement, not just my writing. In that sense, double crux IS erisology, much like a lot of other stuff. Still, I take your point. I’ve not been that interested in DC because both it’s seemed quite plain and because I’ve been more interested in how disagreements *aren’t* about logical chains of premises and conclusions. But sure, it’s a good thing to do to trace back a disagreement to some “clean break” where beliefs diverge. When that does happen it’s very rewarding.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I had similar feelings!

LikeLike