In Wordy Weapons of Is-Ought Alloys I called accusations of racism “the atomic bomb of verbal armaments”. And it is. If successful, it brings a more powerful condemnation on somebody or something than almost anything else does. Everybody knows this, so there’s an obvious incentive to extend its meaning in order to use that power to condemn an increasing variety of thoughts and behaviors.

Looking at how the word is now used, it does seem clear to me that the word no longer has a single cohesive meaning. It has been a victim of what the psychologist Nick Haslam called “concept creep” in a 2016 paper:

Concepts that refer to the negative aspects of human experience and behavior have expanded their meanings so that they now encompass a much broader range of phenomena than before. This expansion takes “horizontal” and “vertical” forms: concepts extend outward to capture qualitatively new phenomena and downward to capture quantitatively less extreme phenomena.

Haslam was referring to the jargon of academic psychology but I don’t think the process only occurs there.

Ever since I started to think about this I’ve been gathering examples of uses of “racism” or “racist” that I’ve heard, seen or remembered. Below is the full list (I include all of it as proof-of-work but feel free to skim it, you’ll get the gist). Even I was surprised at how varied and far-reaching the intended meanings actually were:

disliking people because of their race

wanting to hurt people of particular races

using or even mentioning a racial slur

being violent to someone of a different race

intentionally being rude or less friendly to people of certain races

unintentionally being rude or less friendly to people of certain races

imitating a foreign accent

imitating a person of another race

using IQ tests to select people for jobs

disliking things people sometimes do, if those things correlate with race

believing that any positive or negative characteristic correlate with race

believing that racial stereotypes are based on anything true

believing that basic facial expressions are different between races

believing that basic facial expressions are not different between races

celebrating a person from the past who had views we would now call racist

wanting less immigration

not wanting more immigration

expecting your government to favor your economic interests above those of foreigners

thinking someone else might be biased against you because of their race

having difficulty telling some people of other races apart

saying that [ethnicity] makes the best [ethnic food]

joking about someone’s “ethnic”[1] name sounding like some other word

making a joke about an ingredient in some “ethnic” cuisine

making jokes about it being difficult to see the face of dark-skinned person in the dark

describing someone’s skin tone by comparing it to a kind of food

asking to touch a black person’s hair

wanting your doctor to speak your own language well

wanting local language comprehension a requirement for citizenship

wanting to adopt the culture of a country you’ve moved to instead of keeping your own

believing that intelligence is heritable, even without mentioning race at all

thinking that somebody will dislike you because they are of a particular race you’ve disparaged in the past

thinking that somebody’s race affects their credibility on any race-related issue

being generally rude to a person of another race

disliking social change if that change is a result of changing ethnic demographics

not thinking that being white necessarily comes with noblesse oblige

white people dressing up as black people, no matter how non-maliciously

criticizing Islam

thinking that western civilization and knowledge is better than others

calling a country a “shithole”

telling stories about humans being better than aliens

thinking you shouldn’t change the race of fictional characters

changing the race of fictional characters

wishing that non-white fictional characters were white so you could dress up like them without being racist

making jokes about features of religious clothing

casually claiming that a particular ethnicity is connected a particular culture

wearing dreadlocks as a white person

Apu from The Simpsons

directly or indirectly benefiting from the social consequences of past racism

participating in a racist system

not caring enough about aggregate racial equality as a political goal

being white in america

doing philosophy

Well, that’s long.

I’ll use all this material to do what I used to do at my old job. I worked at a consulting firm specializing in describing societal trends, and when I had a set of examples of some trend or concept or whatever in front of me, my task was to eyeball them, group them into categories, arrange those categories in some sort of overarching model (nine times out of ten it would be a 2×2 matrix) and then talk about it.

Before I start, since this is going to be about “race”, here’s my standard caveat about that word.

This is probably the most complicated article I’ve written so far, so it might be a good idea to be explicit about the argument beforehand. I’ll argue that there’s a core meaning of “racism” that’s reasonably well-delineated and that virtually everyone accepts, but that has been used in various extended senses for long enough to have acquired a set of additional meanings that (1) aren’t well delineated and (2) everyone doesn’t accept. After that I’ll go through a few different ways of looking at how the meanings relate to each other and what different conclusions those different ways support. In the end I’ll tell you the Real Truth.

The one and the nine

The one

Playing around with all my examples, I eventually settled on ten classes of meaning. One of them is special; it’s that core meaning of the word that everyone shares. Simply put, it means liking some people less because of their race. It means caring less when they get hurt, perhaps even wanting to hurt them. It means taking sides in conflicts based on nothing but the races of the participants. And it means thinking that people of some races shouldn’t have the same rights as others. For the rest of the article I’ll call this “racial animus”, or “core racism”.

There are levels to it. It goes from having such feelings deep down that you try to suppress them, to accepting those feelings as legitimate, to willingly acting on them, all the way to wanting them institutionalized in society. But I’m willing to put this in a single bucket for the purposes of this argument due to their uncontroversial status as “racism”.

The nine

Now, there are nine other meanings in my model, and their statuses as “racism” aren’t uncontroversial. This is because they’re not easily separated from more general (not about race) phenomena that, in addition, aren’t always considered wrong.

Since racism is such a powerful condemnation, anything that falls under the definition must be morally wrong, and conversely anything that isn’t morally wrong must not fall under the definition (this isn’t a value judgment by me, it’s my impression of how this discourse actually works). So in many of these cases, disagreement about whether something generally accepted becomes immediately unacceptable as soon as it has something to do with race manifests as disagreement about whether it “is” (should count as) racism or not.

For the rest of the article, I’m going to call these nine meanings — the nine Secondary Racisms — “the secondaries” for short. Here they are:

Type 1: Believing in biologically separate races (“racial essentialism”)

The second type is to believe (link endorsement) that there are, biologically speaking, a set of distinct human races. This certainly used to be the standard view. When I was a kid I liked to read a visual encyclopedia from the 1970’s my mother kept at home (yeah I know, nerrrd). In its section on “Humanity” it had this picture and map that divided people into “caucasoids, negroids, mongoloids and australoids”:

This classification was already on its way out when the book was printed, and still using this or a similar scheme as a biological reality tends to earn a “racism” label today.

It would only be fair to ask exactly how accurate this model is. Well, that’s a remarkably subtle and philosophically complex question (skip to the next section if you’re not interested). It used to be more straightforward in the past when it was believed that things like plant and animal species[3] had essences — an underlying property that says, unequivocally, what kind of thing something is. In that case the question is could be interpreted as “is there one single human essence or a set of distinct ones?”. In other words, “are all people made from the same template or are there different ones?”.

At least that sounds like it could have a correct answer. But essences don’t exist and humans aren’t made from templates at all. “Kinds” and even “species” is a post-hoc construction. In a post-essentialist, anti-Platonic world there is no clearly correct answer and the conclusion depends on a hot mess of interpretation, values and empirics. I wrote about this once in Case Study: The War on Christmas:

People very obviously do look different depending on where in the world their ancestors came from, and the features that vary are correlated, forming clusters. To make an analogy: the spectrum of visible light is continuous, but we still divide it into colors we give different names. Logically speaking you ought to be able to divide humans into races the same way even though you’d have to draw somewhat arbitrary boundaries, just like with colors. Seems like the answer could be “yes”. On the other hand, people’s features vary gradually, and much like the color spectrum form a (multidimensional) continuum. So if you mean “humans come in neatly separate ethnic categories” then the answer is “no”.

Since the answer becomes somewhat subjective it all comes down to attitude and identity. Are you the sort of person who thinks of people in terms of biologically based racial categories or are you the sort of person that thinks of races as an imposed, arbitrary categorization system on top of many continuously varying traits like skin tone, hair type, nose and eye shape, etc.?

Why does this distinction matter? It matters because the idea of separate races used to be the foundation for a particular ideology used to justify what we in the business call quite a lot of very bad things. Full Classic 19th Century Style Racism includes a moral order layered on top of the basic “separate essences”-idea where some are straight-up superior to others in a number of ways and therefore should rule over them with a “divine right” sort of justification. This is a simple thought to formulate in terms of essences[4] because you can just compare the properties of the essences and see which one is “better”, but much more difficult to even think about without them since you have to express it in terms of complicated relationships between attribute distributions[5].

The idea of separate races can be and frequently seen as a remnant of (and irrevocably tainted by) this whole package, which is largely extinct in the western world except for a few pockets outside public discourse.

Type 2: Believing in innate biological differences (“scientific racism”)

Obviously there are biological differences between ethnic groups (skin tones, hair types, facial structures etc.) but the set of beliefs called either “human biodiversity” or “scientific racism” depending on how sympathetic you want to be also includes the idea that the biological underpinnings of mental traits differ significantly — and often that this, or the possiblity of this, should be taken into account when crafting policy. While I’m aware of the content of some of these claims I don’t know nearly enough about them to know how true or false they are, and I’m at the moment quite satisfied with that state of affairs.

My long article about the fight between Sam Harris and Ezra Klein deals with a controversy around the moral status of a claim like this. It started when Sam Harris interviewed the social scientist Charles Murray on his podcast. Murray had gotten into trouble for expressing support for the idea that the difference in IQ scores between races in America likely has a significant genetic component, and Harris asserted Murray’s right to do so without having the “racist” (or similar) label put on him. Klein disagreed that expressing ideas such as this could be considered legitimate at all.

Type 3: Using statistical inference with race as a factor (“racial stereotyping”)

So far I’ve been treating races as biologically and defined two secondary racisms as “applying biological categorization to races” and “applying beliefs about the biological basis of mental traits to races”. Next on the list is “applying statistical inference to races” aka racial stereotyping.

We all know what this means. It means thinking that a black person is good at basketball and likes rap, that an Asian person is good at math and knows how to use chopsticks or that a Jewish person is clever and good at managing money, etc. You get the idea. Many of these are pretty innocent but some (like propensity for crime) can cause real harm.

Using statistical inference on people is frowned upon but ubiquitous. In other words, we do stereotype everybody all the time: if you know that someone is a vegan, crossfitter, atheist, football fan, German, Italian, man or woman that’s going to color your expectations of them at least a little bit. In its most general form, stereotyping means using aggregated information about categories to infer unobserved properties of a single example. We do it with everything — humans, animals and objects. It’s just that animals and objects don’t protest.

Type 4: Drawing attention to racial attributes (“racial othering”)

I was once told that imitating a Japanese accent was racist. I had never thought of it that way. An accent isn’t a deficiency and imitating it isn’t an act of mockery. It’s funny the same way doing an impression of a particular person is funny: because of the recognition factor. It’s not an insult.

This might be a European-vs-American cultural difference (the person who told me was Taiwanese-American). In Europe we speak more than 50 languages on an area the size of the continental United States, and when you communicate with people from somewhere else you speak English and they tend to have an accent. Big deal. So when I think “accent” I think German, Italian, French, Dutch or Russian accents, meaning that they’re coming from people broadly considered historical equals. It doesn’t have the “oppression” angle I imagine it does in America, nor does it have the “visibly different race” association.

Still, there’s a logic to the objection. Imitating an accent associated with a race — which is, as I said above, not a central example of accent to me — raises the salience of race as an attribute. It increases the psychological distance between us and someone else by calling attention to how we belong to different ethnic groups, which is a part of the way towards thinking of them as an “other”. This is potentially dangerous.

Things like wanting to touch a black person’s hair, using makeup and stereotypical clothing to dress up like someone of another race (usually with exaggerated or simplified characteristics), using skin tone when trying to describe what somebody looks like (which I’ve definitely come across people avoiding, sometimes with impressive displays of circumlotion) or just pointing out cultural features like dress style or food in a less than maximally respectful way are also members of this category.

This used to be a lot more common in times and places when we were much less likely to come across people from faraway parts of the world. Like, oh I don’t know, 1950’s Sweden. The picture below is from a popular children’s book series set in the Stone Age called Barna Hedenhös (The Hedenhös Children). I loved these books as a kid, and they are still popular despite pushing 60-70 years. But they have been criticized as racist. For example, consider how the African participants in this stone age version of the Olympics are portrayed:

Or what the natives the family encounters on their trip to America look like:

It would never fly today, of course. We realize that portraying them as “alien” this way (in 1950’s Sweden, they really were “alien” in that most people reading the book had probably never seen a black person in real life, let alone an American Indian) contributes to us empathizing with them less, perhaps to thinking of them as the “out-group”.

I hasten to point out that reading these books makes it very clear that there’s no malice behind these depictions. The books are wonderful in their humanism and in their curiosity and appreciation of other cultures. In one of the first books the kids visit ancient Egypt and marvel at what a magnificently advanced society they have. If anything they sanitize it by not showing the brutal oppression making the Pharao’s lifestyle possible[6].

I bring this up to show that this sort of thing is typically not a matter of racial animus. It’s just that some attributes stand out when you’re not used to seeing them. In decades past these depictions might even have been closer to what people actually saw when looking at people of different races, sort like how a caricature of a person is close to how we see them in our heads.

Noticing what is new and “exotic” to us about other people and thinking of and portraying them in ways that emphasize the things that stand out to us is not peculiar to race. Fundamentally it’s the same thing that makes us notice and comment on somebody being very tall, which is perhaps annoying but not a great sin. It simply gets called racism when applied to something racial.

Type 5: Believing in better and worse cultures (“cultural racism”)

This one is pretty straightforward. Sometimes disapproving of some cultures is considered racist. Common targets are Islamic culture, African-American culture, and in Europe in particular Roma (“gypsy”) culture.

Like with stereotyping, the pattern is strictly independent of race. It can for example refer to subcultures, as in “I don’t like metal fandom, hipsterism, business culture, fundamentalist Christianity or nerd culture” without being something different at the root.

If we cast an even wider net we’ll catch stuff like having an emotional affinity for your own cultural history (if you’re of European descent) or disapproving of the behavior of nations (such as China, Israel, Saudi Arabia or the United States).

Type 6: Wanting to remain the norm (“cultural supremacy”)

I often see the attitude (or, to be perfectly honest, I infer it) that immigrants are welcome to join our community but only as long as we and our group remain the cultural norm.

This can take several forms in practice. It might mean accepting immigration in general but objecting when too many arrive in a short time or when they cluster and form their own local communities and keep their own culture instead of adapting to the local population in terms of language, norms and values. I might also mean thinking that new immigrant don’t have the same rights to try to embed their own values or signifiers in common institutions, or being uncomfortable with ethnic minorities approaching equality in population or cultural influence.

The implication is that an existing culture has a certain right to remain if not “pure” (that’s pretty totalitarian) then at least hegemonic in its own physical and institutional territory. “This is our place and you’re welcome as long as you accept that this is our place” basically. It’s “when in Rome” as a Roman policy.

Ultimately I think this stems from a psychological need for social cohesion through shared frames of reference you can take for granted. I wrote in War on Christmas that there’s a big difference, psychologically, between being part of a culture that’s hegemonic vs. merely primus inter pares. A hegemonic culture implies there’s a thick weave of shared background that makes it easier to communicate with people, feel affinity with them, and feel connected to the community as a whole.

Some need a lot of this to be comfortable and others need less.

At this point I don’t think I’m surprising anybody when I say that this is a general mechanism that doesn’t necessarily has anything to do with race. This article discusses the same thing from a subcultural perspective, calling those who want to keep communities formed around specific interests about those interests vs. becoming just a nice group to hang out in “Possums” and “Otters” respectively. Possums dislike it when new people dilute the community norms that made them feel at home in the first place, and Otters dislike it when Possums are less than welcoming to people that have done nothing wrong.

I think at the core of this is Otters interpreting Possum censorship as something personal, because their standard for feeling a sense of belonging is just “human decency”, and it’s difficult for them to empathize with a motivation of exclusion based on things beyond “human decency”.

Read the whole post, it’s great.

Applying the Possum-Otter axis to immigration reminds me of this passage from one of the more controversial Slate Star Codex posts:

In one model, immigration is a right. You need a very strong reason to take it away from anybody, and such decisions should be carefully inspected to make sure no one is losing the right unfairly. It’s like a store: everyone should be allowed to come in and shop and if a manager refused someone entry then they better have a darned good reason.

In another, immigration is a privilege which members of a community extend at their pleasure to other people whom they think would be a good fit for their community. It’s like a home: you can invite your friends to come live with you, but if someone gives you a vague bad feeling or seems like a good person who’s just incompatible with your current lifestyle, you have the right not to invite them and it would be criminal for them to barge in anyway.

The first version here is the Otter-like position and the second the Possum-like position. Both have their own iron-clad logic, but unfortunately they contradict each other. I don’t know of a way to resolve it that doesn’t screw anyone over, and I suspect it’s one of modernity’s more intractable contradictions.

Type 7: Expecting national loyalty (“nationalism”)

I live in Sweden, a country known for taking in lots of refugees lately. Naturally this causes a fair amount of resistance, and a common complaint is about cost. The argument is that accepting a lot of refugees, supporting them financially through the world’s most generous welfare system and giving them housing and healthcare etc. instead of using that money on tax-paying citizens is wrong; words like “betrayal” or “treason” are occasionally thrown around on social media by the more strident of arguers.

Underneath is the position that as fellow citizens of a nation we have responsibilities towards each other that we don’t have to outsiders, and therefore that the leaders of nations have a responsibility to put the needs of citizens ahead of the needs of foreigners.

This can be seen as straight-up racist as in “the needs of [other race] aren’t as important as ours” because (implied) “we’re better and worth more than them”. But I can’t totally buy that because — and this is becoming this article’s refrain — it doesn’t have to be interpreted that way. Thinking that a community of people ought to have certain responsibilities towards each other they don’t have towards others is yet another idea not fundamentally about race. For example, I consider my responsibility towards my family and close friends to be far above that of other people. I grant their needs and wants higher priority and they are worth more to me, personally, without being “worth more” or “better people” in a general sense — and I don’t need to think that they are to justify my special loyalty to them.

It’s clear to me that, while I don’t feel that way myself particularly strongly, many people have similar ideas about their relationship to the state. That is, they feel that leaders ought to be loyal to their existing populations like people are loyal to their families and friends[7]. This kind of nationalism of course looks like racial animus when the people you do want to be responsible for and the ones you don’t are of different races. But the mechanics are fundamentally the same when they are and when they are not.

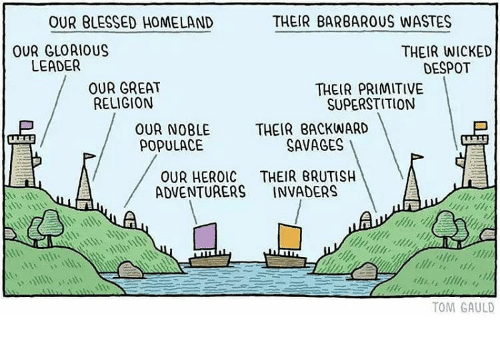

Type 8: Us and Them (“tribalism”)

Tribalism, or dividing people into “us and them” is a cursed practice humanity can’t seem to shake. Whether it’s about countries, neighborhoods, music, movies, food, pronunciation of GIF or choice of text editor, people form camps. We get in-groups and out-groups, friends and enemies, our side and their side, Good and Evil (yes, I think this is part of where the notion of Good and Evil comes from — it’s a reification “us” and “our enemies”).

We even evoke it on purpose and for fun with team sports. That’s good. It’s a way to enjoy the high it brings without the dangers (it can of course still turn pathological and seriously violent with hooliganism).

We even evoke it on purpose and for fun with team sports. That’s good. It’s a way to enjoy the high it brings without the dangers (it can of course still turn pathological and seriously violent with hooliganism).

I’d guess that this is ultimately game-theoretical considerations etched into our psyches. On some primal level we think that shit could hit the fan at at any time and then we’ll have to ruthlessly defend ourselves and our interests to stay alive. We can’t do that alone so we need allies. This applies to everyone and everyone knows this, and thus we are hypersensitive to signs of possible alliance fault lines in a future crisis situation like famine, war or zombie apocalypse. We get a species of hairless monkeys positively obsessed with the minutiae of alliances (up to caring deeply about allegiance to distant people or mere symbols), on a small and large scale.

Often the fault lines will be ethnically based, because that’s an obvious Schelling point. What I mean by that is that ethnicity — in an anthropological sense a braid of genetics, language, religion and history — becomes the fault line partly because everyone expects that it will and knows that everyone knows that everyone knows that it will. This creates a sort of trap where several levels of preemptive fear reactions can cause horrific conflicts to suddenly erupt between people’s who’ve lived side by side for decades. I’m thinking particularly of the Yugoslav war of the 1990’s, which I read a little about when visiting Croatia a few years ago.

One facet of this us-them dynamic is the tendency to view “them” as less than fully human creatures that don’t quite count. This is one of the nastiest features of human psychology and is often activated by language equating people to vermin or poison[8].

This is easier to do if “them” look noticeably different from “us”, but can still happen when outsiders can’t even tell the fighting groups apart like Serbs and Croats, or Hutus and Tutsis, Indians and Pakistani, Spaniards and Basque, Northern Irish protestants and catholics, or Shia and Sunni Iraqis. Like with everything else this isn’t fundamentally about race or ethnicity. Tribalism and subsequent dehumanization can happen based on anything, it’s just easier when you can see it.

Type 9: Discrimination or preference for race-correlated characteristics (“disparate impact”)

I’m told it’s illegal to use IQ tests for recruitment in the United States because it means that, in the aggregate, black people will come out worse. Hence, it is discriminatory — even without explicit discrimination — because of what’s formally called “disparate impact”. Here we talk about discriminating not by race, but by something that’s correlated with race, for whatever reason.

Considering disparate impact to be racism comes from two different sources. The first we recognize from before: the suspicion that you discriminate on something correlating with race because what your really want is to discriminate on race (because of racial animus).

The second looks at consequences instead of causes and calls it racism when it contributes to aggregate racial inequality of outcome. This can be captured in the quasi-Asimovian First Law of Racism: “You shall not do, or allow through inaction, anything that creates, perpetuates or supports an aggregate racial disparity of outcome.”

This maximally expansive definition has evolved as a way to address racial inequalities that can’t be traced back to anyone’s specific wrongdoing. If no one is responsible then no one can be assigned the obligation of fixing it, which is intolerable. So, in an attempt to use the classic “if you’re not part of the solution you’re part of the problem” method of responsibility allocation it files “insufficient regard for aggregate racial outcome inequality as a problem” in under “racism”[9], supported by the implication that the insufficient regard is because of underlying racial animus.

•

Is racism “a thing”?

There we have it. A core meaning and nine secondary meanings.

It wasn’t easy to make this typology. The secondaries blend into each other and there are subtypes and intermediate types and some small exotic variants I’ve missed or ignored, but on the whole I think I’ve managed to map most of the important territory.

What’s the point?

I first started to think about this in 2010 when I overheard two of my colleagues discuss the result of the recent parliamentary election, where the Sweden Democrats, an anti-immigration party with a history of Actual Nazism got a lot more votes than last time and a number of seats in parliament for the first time. One colleague said to the other: “What’s the explanation for this? Are people just racists?”

I remember reacting, in my head, to the way his question was phrased. The important thing here isn’t what explains the rise of the Sweden Democrats, but that the guy asking apparently would consider “people are just racists” to be a satisfactory explanation. As if people had little tags in their heads that said [racist = true] or [racist = false] and all the behaviors, attitudes and beliefs called racist would simply be caused by this underlying property — and not by something else.

This model has the same problem as many others who posit ideas as ultimate causes. Ideas don’t magically appear out of nothing. What causes the ideas? Often the answer seems to be that ideas come from spreading, i.e. people become racists because they hear racist ideas. This doesn’t work as an ultimate explanation because it just passes the buck, but I think it’s many people’s model for how most racism comes about.

Note how well that view lends itself to disease or demonic possession metaphors. There was this one guy at a late night party a few years ago who kept talking about “rasismen” (literally: “the racism”, as opposed to just “rasism”). This use of the definite noun form in Swedish is essentially the equivalent of writing “Racism” with a capital “R” in English, as if it’s a proper noun. To him it was a movement and not a phenomenon (as I would rather have it). Identifying “racism” with a particular political movement and not as a part of the human condition makes it easy to look at it like an distinct force, a disease or a malevolent spirit spreading by contagion, that, if we could destroy it once and for all, would not come back. This idea of there being an separable tumor you can remove or starve while leaving the rest of the body unharmed is of course an attractive image if you want to fight racism.

However, as I’ve tried to illustrate in the list above, I don’t think it’s particularly true. To me what’s called racism looks a lot more like a disparate collection of phenomena grouped together by superficial similarity than a “deep” property or entity that manifests in different ways. It’s a concept more like “round thing” than “gravity”, more like “tool” than “oxygen”. There’s no “root of all racism”.

The implications are a little disheartening. Likely we stand as much chance of workably destroying (all kinds of) racism as we are of workably destroying other sets of things grouped by superficial characteristics like “blue things”, “heavy things”, or “things with sharp edges”. This is precisely because the set of phenomena called racism emerge separately from various types of non-racism by different, understandable, not necessarily pathological processes, not unlike how friction arises from the reality of inertia and the existence of non-smooth surfaces.

The set of secondary racisms are more like many frictions than they’re like one smallpox, so going the extermination route is going to be either ineffective or lead to a whole lot of collateral damage as we try to destroy something without independent and coherent existence. Probably both. What we ought to do is use the institutional equivalents of sandpaper and lubricant to reduce it as much as possible. Unfortunately that’s much less fun than Fighting Evil. Pretty difficult too.

•

Moral overreach

[Note: This section deals with how all the secondaries have not necessarily earned complete moral condemnation and in fact contain large territories of gray area between “very bad” and “quite ok”. It’s fine to skip ahead to “A tale of two tales” if this argument is already understood.]

The expansion of the definition of racism from the core to the secondaries is the extermination strategy being put into action. The core meaning of racism has been successfully stigmatized and have no serious defenders, but the secondaries remain. And so the word gets used more and more liberally in an attempt to get rid of them too, using the same strategy. This is less successful.

The secondaries differ from the core meaning by not being clear cut, both in a definitional and moral sense. So trying to condemn anything that one could possibly call racist according to a maximally expansive definition is going to result in a lot of pretty defensible beliefs and behaviors being targeted. That’s going to backfire.

The first secondary, applying categorization to race, is quite harmless by itself. People categorize. We use categories and “types” as internal representations instead of complex multivariate distributions because it’s easier and it works pretty well in most cases. Applying it to people is morally fraught, granted, but its badness come not directly from categorization itself but from the fact that using category tokens for people opens up the possibility for discriminatory attitudes and practices.

The case is similar for the morality of stereotyping (secondary number 3). I think objecting to stereotyping (in the broad sense of statistical inference applied to people) across the board is going way too far; there’s too much baby in that bathwater. As I said, category formation from clusters of correlated properties is a fundamental part of how human cognition works, or of how any brain’s cognition works, or, hell, of how the cognition of any pattern-matching intelligent system works. You have to use knowledge about apples in general to assume that the uneaten apple in front of you is in fact safe to eat and not poisonous or explosive. It’s not possible to avoid this completely.

One moral problem is when you let category-level information override higher quality information at the individual level — i.e. you treat people as members of a category and not individuals even when the second is possible. We’re essentially morally obligated to eagerly abandon category-level assumptions as soon as individual-level information starts coming in. Not doing that is pretty close to what people are referring to when they say “stereotyping”.

Another is when you allow category-level information to have real consequences for a person without having any individual-level information to rely on. But there are complications, because statistically speaking what may be immoral here is not necessarily irrational, and demanding that people be irrational for moral reasons is a big thing to ask. How justified it is depends, I think, on the costs to both parties, and this moral issue eludes a neat answer.

Finally, sloppy and eager stereotyping could be evidence of racial animus — you may simply not care enough about someone of a different race to be particularly concerned about whether your stereotypically founded impression of them actually reflect a true statistical tendency or is a complete fabrication. As far as I understand it, most people who are fundamentally hostile to stereotyping believe on some level that they are almost always false. Given that, it’s easy to condemn the whole practice.

However, I believe that stereotypes are often accurate, as research suggests and in addition I believe that people who dismiss the accuracy of stereotypes wholesale are engaging in some serious self-deception with the purpose of making things easier than they are.

If stereotypes are not generally false and not necessarily a result of racial animus it becomes much harder to make definite moral judgments about how much stereotyping is permitted.

If only we could wish away tensions and contradictions. Or define them out of existence.

The third secondary is beliefs about innate average racial differences in important mental traits (like the beliefs apparently held by Charles Murray that I described above) and it has similar issues. It’s possible, even likely, that many to most who believe such claims are willing to make that call because they harbor racial animus. But many, including me, resist the idea that the logical distinction between factual beliefs and attitudes can and should be collapsed so that factual beliefs themselves can be considered enough to constitute racism.

This is how I interpret Sam Harris’s position in the controversy I wrote about. He argues that Murray seemingly believes what he believes because he finds it the most likely interpretation of the available evidence, and this doesn’t justify putting the “racist” label on him, directly or by implication. If it did, it would imply that we should morally condemn someone merely for holding certain factual beliefs and if we try to reconcile this with the rather obvious principle that (beliefs about) facts are distinct from values we wind up with an ugly, unprincipled and poorly delineated exception (what about outcome-relevant physical differences?) for beliefs specifically about race.

•

The issues with drawing attention to racial attributes are quite different (secondary number 4). In the milder cases it’s a matter of etiquette rather than morality, and therefore subject to the sort of ongoing implicit renegotiation where personal experiences matter a lot, tempers run high, differences of opinion are rarely exhaustively aired and there are few objective standards. Caution is encouraged when making judgments here.

It’s more serious when a strong argument can be made that this behavior directly and significantly contributes to dehumanization — such as when a depiction is obviously mean-spirited. I don’t have a rigorous way to define this, but I think my general point has been made by just saying that these practices exist on a spectrum from the innocent to the nasty, and placing them in the same loaded category means an unjustified contagion of “bad karma” from the nasty end to the innocent end.

Turning to cultural matters, that is, secondaries number 5 (disliking some cultures) and 6 (wanting to remain the norm), mean confronting what I think are the hardest moral problems to tackle.

It’s hard to justify calling it categorically wrong to dislike some cultures. Cultures consist of values, behaviors and norms, and it must be permissible to disapprove of such things or we rule out having any values whatsoever. There’s no obvious line you cross when you disapprove of something that happens to be part of a particular culture[10]. Hell, you can disapprove of something without knowing that it’s part of another culture.

Perhaps you do cross a line when you go from disapproving of some elements of a culture to disapproving of the whole culture, but this is a subtle difference that can easily be confused by unclear language or unclear thinking. Nobody dislikes every single aspect of a culture taken in isolation. You’re definitely on thin moral ice if you let negative attitudes about some elements spill over to the culture in general, and from there to other elements you wouldn’t dislike in isolation and especially to every member of the ethnic group the culture is associated with.

Again like with stereotyping, there seem to be people who believe that dislike of cultures is necessarily downstream from racial animus. I don’t think they’re always wrong, but I certainly don’t think they’re always right either. In fact I wouldn’t be surprised if racial animus is less fundamental than cultural animus — by which I mean that when people dislike other races what they really dislike is often other cultures and race is used as a proxy (“I don’t like people who behave this way and people who look like that tend to do so and therefore I don’t like those people”). It’s a combination of stereotyping and disliking cultures that gives rise to a new, dangerous effect… but I’m getting ahead of myself. The important part is that this also fits on a wide moral spectrum from “justified” to “bigoted”.

When it comes to expecting to remain the norm in your community I also find it easy to see problems but hard to condemn it categorically. I very much understand the desire to be surrounded by like-minded people and take a lot of cultural background factors for granted.

So I feel the need to mount some defense for the “Possums” who want to screen new members of a community for cultural fit or demand that they assimilate, because while I understand both positions I contend that the Possums’ feelings are unfairly maligned in many quarters today. I really do get the alienation and existential dread that dilution of cohesive norms induces, and I think it’s understandable to be uncomfortable with the idea that anyone is fully entitled to both become part of any community they want and when they’re there work to change it in whatever way they want. It leaves no legitimate way at all for communities to control their own futures.

Wanting to preserve cultural cohesion is perfectly understandable and there are good reasons to believe that its deterioration accompanies a decline in social capital. However, in practice it necessitates “gatekeeping” behavior and an unpleasant sort of hierarchy where the new, the different and the nonconformist are relegated to second class status. National-level Possumism risks becoming unacceptably repressive, especially in modern societies that already are wildly diverse along all kinds of axes. It’s too much in tension with the necessary consequences of non-negotiable ideals like individual rights and pluralism. These are hard-won, vital principles that are worth paying a price for.

That does not mean that the feeling should be considered automatically suspect and be denigrated, denied, delegitimized or pathologized, as I feel it often is. Again we have a situation when something fundamentally legitimate can gradually become unacceptable when turned up high.

•

I have little to say about secondary number 7 about states having special responsibilities towards its citizens other than pointing out how similar it is to the last example: while there’s obviously some cases where we accept it and it’s generally moral to give this kind of in-group loyalty a sympathetic hearing, the risk of metastasizing into something straight-up nasty justifies some caution.

Metastasizing into what? The eighth secondary: us-and-them thinking. While this behavior is obviously destructive, it is also hard to categorically condemn because in a crisis situation people do what they need to do to survive, and we typically can’t afford the same basket of morality we buy in times of prosperity (which is why it’s so damn important to protect prosperity). Still, some people are clearly quicker and more willing than others to enter crisis mode, to think we’re in crisis mode already, and to wholeheartedly embrace it. That’s something to be suspicious about.

The final, ninth secondary is a continuous moral grey area par excellence. I can certainly understand the worry about “indirect” discrimination performed by either individuals, institutions, or society as a whole. But if we generalize that principle we wind up in a weird place for similar reasons we do if we say that you can’t dislike a culture. If it’s racist to like/respect/reward or punish people based on characteristics that correlate with race[11] then a whole lot of quite rational and defensible personal attitudes and institutional processes are going to have to go — because lots of things correlate with race for various reasons, like class[12].

The problem with the maximally expansive Asimovian First Law of Racism ought to be clear: it makes people responsible for things they haven’t done and saddle them with effectively limitless responsibility by trying to bring the full force of the “racism” label down on things that clearly aren’t bad enough to qualify. And if you stretch something too far it will break.

•

A tale of two tales

I’ve implied that the extension of the core definition of racism into a number of adjacent territories is a strategy — a strategy akin to carpet-bombing cities to destroy munitions factories. The justifying narrative paints racism as a singular phenomenon, which is easily mistaken for an entity, one that can and should be fought. It’s a bit like how conceiving of “international communism” as an entity justifies bombing Vietnamese jungles as part of an existential struggle.

While this is largely implicit, I think the process of constructing that story goes something like this:

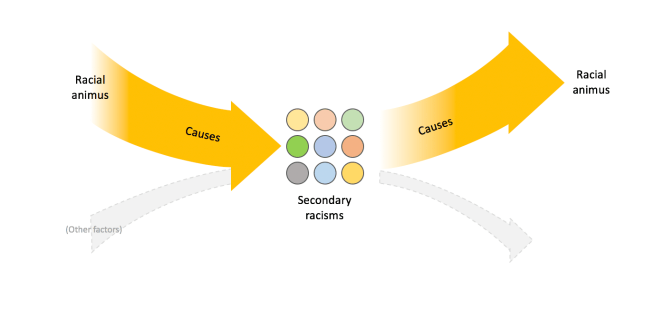

All of the secondaries can occur by mechanisms independent of racial animus, yes, but they can also happen, or be made more likely to happen, because of underlying racial animus. They may also, in turn, cause racial animus. Putting it all together gives us a model where the secondaries are partially caused by racial animus, and in turn partially cause it.

How can we derive different models from this one? Imagine that you think that the secondaries are virtually always caused by racial animus and the importance of other causes like general, valid cognitive and emotional processes are negligible, and at the same time you think that the secondaries in turn reliably cause racial animus and the extent to which they don’t is similarly negligible. These are easy, not obviously unreasonable simplifications. You get this:

This easily and elegantly compresses into a self-caused, self-perpetuating cycle called “racism”.

This easily and elegantly compresses into a self-caused, self-perpetuating cycle called “racism”.

Disregarding the “leakages” at each causal end makes it possible to conceive of Racism as a closed system, a unified system with few meaningful internal differences. And I suspect that, for many, the distinction between “racial animus causes the secondaries” and “the secondaries cause racial animus” fades away like unused neurons. Instead of a causal, logical, reductionist story about interacting parts we get a structural, functional, holistic story about an organic whole. In this model, racial animus is expressed in the secondaries, which are used to justify the racial animus.

This unification plays its part in giving the label rhetorical reach and power. The less obviously and/or grievously immoral examples all get their status as unacceptable by being part of a whole with the worst kinds.

This puts the oft-mocked phrase “I’m not racist, but…” in a new light. It’s portrayed as little more than a sign that a person is about to say something profoundly racist but wants to pretend they’re not racist. But I think its true purpose is to implicitly reject the unified model in favor of another, where most kinds of racism are really applications of more general (and then more accepted) mechanisms to race in particular. What it means is “I don’t harbor any particular antipathy or disregard for people of [race], and what I intend to say should be thought of as the application of a principle not fundamentally about race (e.g category inference, statistical beliefs about people, disapproval of certain behaviors, desire for cultural unity, moderate in-group loyalty etc.), to something that happens to be about race this time”[13].

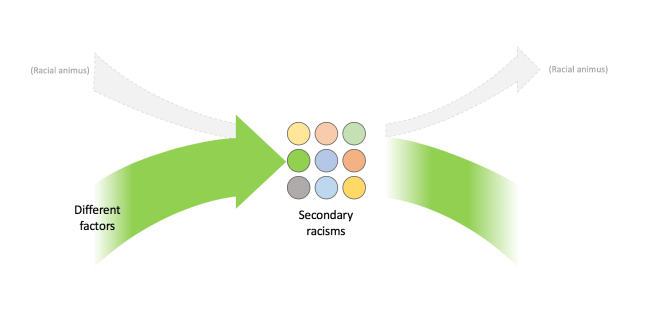

The problem with the self-perpetuation model is not that it’s false, because it’s not. It’s that it’s true enough to feel completely true, and it’s not that either. I think what it rounds off and discards is important enough that leaving it out leads us to the wrong conclusions. Part of my skepticism is a personal philosophical bias against “self-caused” phenomena in general[14]. But that’s not the whole reason. There’s important information in what the self-perpetuating model leaves out, and we can build another narrative out of that remainder: the secondaries are caused by things other than racial animus and they do not cause racial animus. The engine never starts spinning. It’s just there.

Is this correct? It might sound like I think it is, but no. It’s partially correct, like its opposite. They’re both what I’ve previously called partial narratives, two different ways of making sense of the same things, characterized by two very different approaches. I’ve written before about the political use of making distinctions and separating things from each other vs. making connections and grouping things together. These two narratives are very much characterized by these opposite practices — coupling and decoupling. The self-perpetuating entity model is highly coupled, and the bag of independent phenomena model is highly decoupled.

Where do we go from here? Any narrative is going to be partial and the best way to handle this fact is to gather as many as you can and try to perceive a higher truth in the resulting gestalt. But there’s also another possibility. Just because all narratives are partial doesn’t mean we can’t improve on a given set of narratives. Is there a better way to think of “racism”? Can we have a narrative that combines at least some of the benefits from both the coupled and the decoupled versions?

Yes, I think we can.

•

The general factor of racism

Think about intelligence for a minute. Intelligence as a scientific construct is a result of the fact that cognitive abilities, when tested, correlate with each other. If you’re good at reading you’re also more likely to be good at counting, at mentally rotating shapes, even at reacting quickly. It didn’t have to be this way, but the research shows that it is.

This has led psychologists to posit an underlying property making us generally better or worse at this kind of task. The “general factor of cognitive ability” is abbreviated “g” (which is related to but not the same as the property that for historical reasons is called “IQ”).

Here’s what I’m getting at: is there’s a similar “general factor of racism”? Do the core meaning and all the secondaries correlate with each other the way mental abilities do? I’m going to assume, for the sake of argument, that they do.

Doesn’t this mean that racism is “one thing” after all? Not necessarily, and it’s here I think the analogy to intelligence really shines: it’s currently not known whether g is traceable back to any single property that represents “intelligence” neurologically. It’s possible that mental abilities has a way of supporting and reinforcing each other in such a way that a general factor of intelligence emerges without there being a single driver behind it (I saw a paper a while ago that made this argument but unfortunately I can’t find it again). Whether or not this is true of intelligence, I find it the most fitting way to think of racism.

While logically distinct, the secondaries are sort of narratively compatible with each other. They support similar explanations for why the world is the way it is and assign positive and negative valence to much the same things. That makes rejecting or accepting them as a package a high-consistency, low-cognitive-effort-and-dissonance option. You can “be a racist” in all these ways without much difficulty, but if you want to accept some and not others, you’ve got a lot of careful cognitive work to do.

Above I’ve hinted at how individually innocuous secondaries become more dangerous when combined: beliefs about biological differences with essentialism, cultural dislike with emphasizing racial attributes, national loyalty with tribalism, etc. The more of them you put together, the more foul-smelling the result seems to get. Following this to its logical conclusion, I think “racial animus is the driver” might be wrong specifically because it characterizes racial animus as separate from but existing on the same level as the secondaries, interacting with them. Instead I suspect racial animus exists only as an emergent phenomenon arising from the totality of connected secondaries, sort of like how the meaning of a phrase arises from the totality of its words. Or, to get a little pretentious, like how consciousness arises from a totality of non-conscious parts instead of being a fundamental substance or property. I guess I’m an emergentist about racism and what I’m disagreeing with is something like dualism.

I also find this model useful because of how well it handles my own ambivalence (an ambivalence this article can thank for its existence) towards the way the “racism” concept has been constructed lately. There’s a contradiction between my discomfort with blanket demonization of anything that was ever in the same area code as core racism and the opposing but equally compelling conviction that this particular knot in idea-space is cursed and should be given a wide berth. This model resolves (or at least explains) it: core racism emerges gradually — unless you’re extremely careful and equipped with a powerful moral compass and exceptional decoupling skills — when you assemble certain non-objectionable materials in the “right” way.

It’s as if it was possible to make high-powered explosives by just mixing salt, flour and orange juice. It wouldn’t be justified to ban them or put anyone who buys them under surveillance or even suspicion. But nor do we want people blowing shit up all the time. Clearly, we need to be cautious, mature and measured to deal with this issue. Lucky for us, Twitter exists.

•

Racism as an ideology

I don’t know if this “narrative fit” is primarily psychological or social. By that I mean that maybe the best explanation is that narrative compatibility is attractive because it reduces cognitive dissonance, or it’s that ideas spread along social connections that form because narratively compatible ideas in different people make those people into natural allies.

We do have a name for clusters of logically separable but mutually reinforcing ideas with political significance — they’re called “ideologies”. The taking apart I’ve done here with racism could be done to our old classics like socialism, liberalism, conservatism, anarchism etc. because they are also clusters of values, narratives, attitudes and empirical beliefs that we often lump together and treat as a unit. This is a simplification and doesn’t describe every person (but when it does I suspect the structure produces some sort of emergent attitude/emotion like racial animus/core racism is).

Just assuming that someone accepts an ideology wholesale just because they express affinity to some part of it is unfair, but of course we do it all the time when arguing with strangers on the internet because it’s simpler, it saves effort, and it gives you what you want — which is to attack an ideology as a whole and not the exact views of one particular person you don’t know or care about.

How unjustified it is to treat a person as an avatar of an ideology depends of course on how well their beliefs actually match it, but also on how well-regarded the ideology is. A big difference between the United States and Sweden (the two political cultures I’m most familiar with) seems to be the willingness of someone supporting high taxes and a generous social safety net but not an end to private capital ownership to call themselves a socialist (although this seems to be changing lately). In Sweden this is fairly normal and legitimate, while the label carries a stigma in the US. Conversely, there are few in Sweden who call themselves conservatives (this is also changing a bit). I think this makes more unfair to assume that a random American is a socialist because they want to raise taxes than assuming the same thing about a random Swede. Vice versa with “conservative”.

The cluster of “racisms” as a whole — i.e. the ideology — is not considered legitimate in public life anywhere in the western world and if you subscribe to any part of that cluster whatsoever, you do everything within your power to distance yourself from the rest. This makes the situation a bit different compared to other ideologies. Having some leftist or rightist opinions means you can call yourself “left-leaning” or “right-leaning” without much issue. But no one ever says “I’m racist-leaning” even though it would be a technically accurate description of some.

That bring us back to the phrase “I’m not racist, but…” and suggests yet another interpretation I think is even better: it means that the person talking subscribes to some ideas in the cluster but not the ideology as a whole. Equivalents would be “I’m not a socialist but I think we should tax the rich more”, “I’m not a Christian but I think Jesus had some good ideas”, or “I’m not a conservative but I think we should be careful about changing society too radically etc.” Further examples are left as an exercise for the reader.

If these other ideologies were as illegitimate as racism I bet we’d see more of these. I don’t know if people used to say “I’m not a communist, but…” in 1950’s America, but it would’ve made sense.

•

In summary

Despite the fact that the definition has been expanding in various directions onto what I consider new and separate meanings, it’s still common to think of “racism” as if it was a single property or thing. It’s understandable if you make certain simplifying assumptions and it’s sound reasoning, consequentially speaking, if you want to fight it, because then treating everything that contributes to it as equally morally unacceptable could help — like putting a blockade on a port to starve it, denying it the nourishment of justifications.

But I don’t think it’s an accurate representation of reality, and brushing all such concerns aside in favor of a “the ends justifies the means” approach have a tendency to backfire, because there is only so much tension with reality a concept can withstand.

Yet there is, conceivably, an “ideology of racism” consisting of many separate yet mutually reinforcing ideas and behaviors. But eagerly making the leap to considering any part of an ideology a representative of the whole is in this particular case less justified than doing the same with more legitimate ideologies like socialism, Protestantism, feminism or libertarianism. Because of the strong, virtually universally upheld moral stigma, doing so artificially magnifies the badness of minor sins or even non-sins by bundling them together both with each other and with greater sins, making each carry the weight of the whole. It’s collective guilt, but with memes instead of people.

• • •

Notes

[1]

Yes, “ethnic” in this sense is a stupid word, all names are ethnic.

[2]

The word “race” weirds me out. It doesn’t exist in my mother tongue (outside some unsavory circles) except as an archaic term only still used to talk about breeds of domesticated animals. Words like “ethnicity” or “people group” are used instead. I’ll still use “race” here since it’s used in English and can’t really be avoided.

[3]

For example: part of what made it difficult for evolution to be accepted in the beginning was the assumption that species had unchanging essences since the creation of the world and could not “turn into each other”. But they can, and essences don’t exist.

[4]

It was also common to think that there’s something bad about “race mixing”, which sort of makes sense if you believe essences are real. Given a modern understanding of biology there’s a much stronger case that genetic diversity is actually beneficial.

[5]

The popular claim that “race doesn’t exist” or “there is no biological basis of race” means essentially that: there aren’t a set of distinct biological categories that correspond to what we usually think of as races. This serves to make it impossible for such a categorization scheme to support the ideological superstructure it used to support. Unfortunately it tends to be overinterpreted (and those who say it tend to let that happen, which I think is a mistake) as “there exist no patterns of physical biological difference between what we commonly understand as races at all”, which is of course false since we can see them with our own eyes just like we can see that color can be different despite the spectrum being continuous.

[6]

But then again it’s a children’s book.

[7]

This view might be especially resonant among traditionalists here in Sweden because the state has historically been explicitly compared to a big family as part of national community building with the purpose of diffusing class conflict.

[8]

As far as I can tell, this dehumanization switch is so off-and-on that it’s perhaps a psychological adaptation, something there to help us ruthlessly pursue the interests of our group and ourselves while still being able to be kind and caring to our own people without short-circuiting our minds.

[9]

This is similar to how people on the economic far left sometimes use “capitalist” to refer to anyone supporting the right to private ownership of capital, even though the word in its original Marxist sense denoted a small, particular class of property owners.

[10]

Sure, there’s an argument that you shouldn’t disapprove of elements of a foreign culture because you don’t have the necessary context to understand it. It could serve an important function you can’t appreciate. Fine, it’s a valid point — in theory. Its validity tends to disintegrate on leaving the lab environment and making contact with reality. I don’t see an obvious difference between your own and another culture here, because we don’t necessarily understand all the functions of everything in our own culture just because we’re part of it. And what counts as “another” culture anyway? What about a subculture you don’t belong to? What about our own past? If your culture interacts with another one, can you have opinions on how they act in that interaction? Does understanding of human nature not grant us enough insight to make at least some judgments? Such as that people everywhere generally find peace, safety, prosperity and freedom desirable?

[11]

I’ve been thinking about this issue in the context of sexism, where the situation is similar. If men and women tend to have different personalities on average (and they do, whatever the exact reason), are you a sexist if you find personality traits more common in one sex more virtuous? To use a silly example: what if you thought that the physically weak were pitiful and respected people in proportion to how much they could bench press? You’d respect the average woman far less than the average man. Some would call it sexist but I’m not so sure. I think it matters greatly what causes what. Do you respect men more because you value strength, or do you value strength because you respect men (and therefore “male” virtues) more? This is not a trivial question.

[12]

I can’t prove it but I suspect a lot of racism is actually classism, where race is used as a proxy for class.

[13]

A less charitable way to phrase it would be that it’s an attempt to justify your racial animus by arguing that it’s in fact a rational consequence of other, acceptable beliefs and not simply caused by itself: “You’ve got it backwards, my racism doesn’t cause me to think this, thinking this is what causes my racism, and therefore you can’t dismiss what I say as simple motivated thinking.” In any case it’s a phrase that has a particular meaning even if it sounds like an empty excuse, and that suggests a different and more sophisticated type of counter than a straight-up “I hate [race]” type statement would.

[14]

I don’t tend to think any of the things people often seem to think of as disconnected from the “ground”, apparently self-caused and self-perpetuating in a top-down fashion and potentially removable or freely alterable (more like smallpox than friction),

— like religion, war, self-interest or inequality — actually are like that (but that is a much, much bigger issue).

Did you enjoy this article? Consider supporting Everything Studies on Patreon.

With regard to type 4: This is probably easier for an American to understand than a European – it’s not just about salience. In the United States, there is a long history of derogatory racial caricature. So an American black person looking at the pictures in those children’s books is going to have a really hard time not associating those relatively benign caricatures with the historical, derogatory ones.

LikeLike

So I think that for a lot of people, blackface is “something you shouldn’t do because it offends black people and is therefore rude”, not “something you shouldn’t do because it indicates racial animus.” Of course, unified-system people don’t necessarily recognize this distinction.

LikeLike

The link to the Possums and Otters essay is bad. (You spelled the site “knowlingless” instead of “knowingless”.

LikeLike

Thanks, fixed.

LikeLike

Here’s a blog post relevant to footnote 12:

http://datacolada.org/51

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Île Flottante .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Regarding “general factors”, this SlateStarCodex post discusses them, specifically relating to intelligence, as illustrated by the case of comas. Probably not the paper you couldn’t find, but still relevant.

LikeLiked by 1 person