[Note: Quick and off the cuff. Quality may have suffered.]

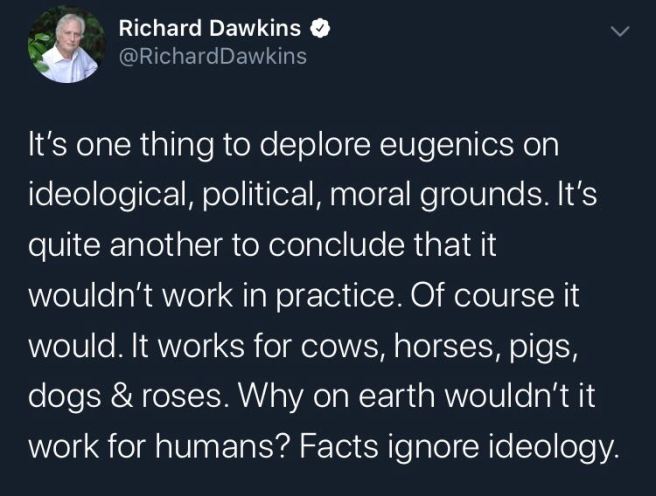

Yesterday famous biologist Richard Dawkins said this:

…and all hell broke loose on Twitter for the first time since, like, Wednesday.

I scrolled past the tweet the first time and made hardly any note of it. A obvious, plain point. He complained about how people conflate something being undesirable with it being impossible. And sure, that’s a generally popular argumentative trope people pull out when they want to be extra safe and get a little too bold and greedy: “no there can’t even be a trade-off, this has to be a delusion in addition to evil”[1][2]. So, yeah. Nothing noteworthy.

But it blew up, with comments and quote-tweets flying around. It reached the level where people would talk about the whole thing right into the Twitter-aether without quoting anything, just assuming that everyone already knew the topic — which signifies at least a level 6 quake on the Twichter scale. I was surprised at the heat, even though I shouldn’t be at this point. There are so many of these incidents. I guess I do underestimate how strong a rationality dampening field some terms project. “Eugenics” is clearly up there near the top of the list (along with “incel” and “racism“).

Not that I don’t get it. It makes perfect sense to be wary of eugenics, of course, and everyone should be to some extent. But when discussing in the abstract (in this case on the meta-level — as in discussing the discussion), something that’s not even close to happening, it’s a little odd that reactions get as extreme as they often do. There’s no clear and present danger to justify being extremely trigger-happy. It all seems like two orders of magnitude out of proportion, as if the Chernobyl disaster having happened made some people freak out at the mere mention of setting foot anywhere on the Eurasian continent. That’s my reaction, anyway. I might be wrong for some specific contexts.

I fell for the controversy for a while, thinking to myself that people who read something evil into this and went hysterical over it were totally fucking insane[3]. But they’re not. It’s me — and I really should know better since this is like two thirds of what I talk about on here — underestimating how flexible interpretations can be[4].

On the surface this is just another case of people disagreeing on the proper dosage of decoupling. I’m not going over that again this time. Instead I got interested in the second hand debate in the wake, on what “eugenics” means. Shockingly, people aren’t on the same page.

After reading behind some lines while trying to be fair, and filling in some blank spaces between, I’ve compiled a non-exhaustive list of candidates:

Using government power to prevent people with undesirable traits from procreating.

Having any third party interfere in a couple’s reproductive choices for the purposes of improving heritable traits.

Taking any action at all with the intent of improving the genetic endowment of any person.

Eliminating heritable diseases through gene therapy.

Having children with somebody whose traits you want for your child[5].

Forcibly sterilizing poor people and/or ethnic minorities.

Voluntarily letting people edit their children-to-be’s genomes.

Encouraging, financially or otherwise, bright and well-behaved people to reproduce.

Significantly, reliably and effectively cultivate a specific desired trait in people with no adverse effects, using genetics as the lever.

Improving society by means of selective breeding of people.

Any policy with the aim of improving the genetic health of the population.

Any policy with the aim of changing mental or behavioral traits on the genetic level in the population[6].

I think that’s enough to map out most of the moving parts underneath. To me these three seem to be the biggest (but certainly not the only) factors in dispute:

1. Is coercion necessarily involved or do softer negative or even positive incentives also count?

2. Does it have to involve any change in who reproduces and how much, or does direct genetic engineering also count?

3. Is the hypothetical goal narrow, like “cause a change in the frequency of a trait”, or broad, like “solve significant social problems”?

It’s a lot like designing your gaming character. There are a number of sliders to move around to create your own custom meaning of “eugenics”, tailored to whatever rhetorical purpose you have at the moment, that people of varying persuasions certainly make use of. If we set up an interpretation matrix of the two little words “eugenics works” it’d be multidimensional and complicated as hell, and the moral charge of each cell would vary dramatically. A minefield is an apt analogy.

If we’d just pick up one minimally and one maximally controversial version (a motte-and-bailey pair, as it’s sometimes called) as examples it’d probably be something like this:

It would be technically possible to change the frequency of human behavioral traits in roughly the desired direction by taking some actions that alters the future gene pool.

vs.

We could make society better by a policy of selective breeding where we restrict undesirables from reproducing[7].

The actual content of these two are different enough, but also think about how much of a difference the language makes. Saying “selective breeding” about people as if they were crops or livestock triggers our ick-feelings, the word “undesirables” have all sorts of awful associations, and while “we could…” can mean the same as “it would be technically possible to…”, it opens up a lot of interpretation-space in the direction of it being a seriously intended proposal.

•

There are many concepts like this, where the meaning is fuzzy and constantly shifting but people tend to act like it’s not. In part they’re trying to enforce their own meaning by pretending, to both others and themselves, that it’s the canonical or “real” one.

It’s really hard to deal with this kind of interpretive flexibility when speaker and audience are on hostile terms. We don’t know what we don’t know: we don’t know which of our own words other people will interpret differently and how, and we don’t know which of other people’s words they mean differently and how. As a speaker you can clarify, but when you do so you’ll use words again, and they’re subject to the same problem. And even if you make an effort to be very clear about what you mean and don’t mean, some will ignore it anyway (I discuss this briefly in my long postmortem of the Harris-Klein debacle). That’s not necessarily irrational, as some in the audience are likely ignore it as well and come away with a bad or dangerous message, but it puts an almost unsurmountable burden on anyone speaking on sensitive issues. Do you have to cater to the least reasonable audience member on every side?

Personally I can’t accept that. On a medium like Twitter in particular where you’re limited to 280 characters and the product idea is “decontextualization as a service”, you can’t clarify with enough detail to protect yourself against hostile interpretation. Language itself wasn’t built for that shit. I can’t easily think up a rephrasing of Dawkins’s tweet that would’ve made the same point but made it impossible to interpret in a bad way given enough will, certainly not given the character restriction.

Still, some who disliked the hysteria still maintained that Dawkins should take some of the blame for not being more diplomatic or spend more effort clarifying things he has every reason to believe would be obvious to every reasonable person. I really can’t agree with that either. In a context like this, for reasons stated above, the onus has to fall mostly on the audience to spend a few cycles to think about what somebody means and default to giving people the benefit of the doubt.

• • •

Notes

[1]

Note that I’m virtually certain you could point to examples of Dawkins himself doing the same with religion.

[2]

One sign of this is people coming up with really weird and tortured reasons for why things they don’t want wouldn’t be possible anyway. Honestly I’m not innocent myself. I catch myself doing it at work on occasion when I really don’t want to do a thing.

[3]

It can be quite enjoyable to think like that. I recommend a few minutes of it as a weekend treat. Certainly not as a steady diet.

[4]

I come back to this paragraph from one of my early pieces (that was further developed here):

An encounter with an ambiguous yet controversial-sounding claim starts with an instinctive emotional reaction. We infer the intentions or agenda behind the claim, interpret it in the way most compatible with our own attitude, and then immediately forget the second step ever happened and confuse the intended meaning with our own interpretation. This is a complicated way of saying that if you feel a statement is part of a rival political narrative you’ll unconsciously interpret it to mean something false or unreasonable, and then think you disagree with people politically because they say false and unreasonable things.

[5]

This could reasonably be said to lie so far outside any common use of “eugenics” as to be disingenious. Kind of. The intention isn’t literally to claim that this should be called eugenics, rather it’s an attempt to establish that acknowledging that some heritable traits are desirable and acting on that is a normal and reasonable thing on a personal level. This anchor sets up a spectrum between acceptable and unacceptable eugenics-like things, which makes it harder to ignore the complicating gray area of non-coercive but functionally eugenic practices in between. It’s weird and fascinating how much of this sophisticated mechanism works subconsciously.

[6]

Note that the difference between “poor health” and “undesirable mental and behavioral traits” isn’t clear cut at all.

[7]

These aren’t anywhere near unambiguous either of course. They each have their own interpretation matrices, but less vague ones than the original.

Did you enjoy this article? Consider supporting Everything Studies on Patreon.

The historical usage of the term is pretty much exactly this:

“Any policy with the aim of improving the genetic health of the population.”

Note that the last part – “of the population” – is crucial. This doesn’t count:

“Having children with somebody whose traits you want for your child.”

In practice, very few voluntary, individual decisions count as “eugenics” in this sense, because – contrary to Francis Galton’s hopes – very few people are willing to prioritize something like “the genetic health of the population” over what they want for their own family.

Of course, it’s common for people to use “eugenics” in senses other than the historical sense, but I feel fairly comfortable calling them wrong, since the goal of calling something “eugenics” is almost alway to link it to the historical movement.

LikeLike

Yeah I know, see the footnote on that one. I’ve always had that historical definition in mind as well, but many treats it as being necessarily coercive.

LikeLike

Nearly all or all forms of eugenics that people can bring to mind are coercive; the examples he gives in the tweet are coercive; the historical examples of eugenics are coercive.

There are things you could argue that are forms of eugenics that aren’t coercive, like offering free abortions or free birth control which is disproportionately used for fetuses / parents with genetic disorders (and indeed in countries with universal health care coverage and legal abortion, this is often the case); but critically these are free to anyone, so if people without genetic disorders accessed them at a higher rate than those with, then it would be anti-eugenic. There are people who argue that the fact that people are accessing abortion for fetuses with Down Syndrome in Nordic countries for free is eugenic, but I disagree with them.

If you *only* offered these things for free if the fetus has a genetic disorder, then I would agree that’s eugenics, but then I would also consider it coercive. So essentially I’m having trouble coming up with something eugenic that is also not coercive. I think perhaps if you use the definition of eugenics of being anything causing changing in gene frequency, then free abortion and birth control through a national healthcare system could be considered that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Imagine that the government doesn’t subsidize abortions for genetic disorders, but does release regular public service announcements about the importance of aborting fetuses with genetic defects. That doesn’t seem coercive to me, but it does seem eugenic. I think the problem isn’t so much coercion as it is discrimination; the PSAs in question declare that people with genetic defects are less worthy of life than those without.

LikeLike

I feel like there is a camp #1 of people out there who read something like Dawkin’s tweet and think — oh yes, sure, that’s patently obvious, no problem there.

And then there is a huge camp #2 who read something and think — what the fuck? are you trying to defend eugenics?

and these two camps seem to basically not understand each other at all.

Camp #1 responds to camp #2 like your post: what the fuck is going on? of course it’s true. It’s obviously true. Here’s (a). Of course Dawkins couldn’t spell the full idea out in an unobjectionable way in a single tweet, but come on, he clearly didn’t say the bad thing you’re assuming he meant. You are clearly in camp #1.

Camp #2 responds to camp #1 with: “what the fuck is going on? why are you all defending eugenics? are you trying to slip ideas into our popular consciousness that this is actually fine and good?”

I think they’re both right, but I think camp #2 is more right. I think that you, and all the other people in camp #1, are really missing the point.

Objectively, Dawkin’s statement is correct. Objectively, with more words he could have probably crafted a version with more equivocation that would seem a bit more palatable in public. Objectively, facts ignore ideology, and yes clearly we could breed better humans by trying.

Camp #2’s objection isn’t to any of this. Camp #2’s objection is to the presence and normalization of saying it, and they’re especially wary of it because this kind of thing happens all the time on the internet these days: bait-y pseudo-intellectual trolling of the form “yes of course we should be fair to everyone but objectively white people are smartest” or “yes of course we should people should be free to do whatever they want but clearly men should be working and women should be breeding” or whatever. It’s repackaging regressive opinions as self-aware versions of the same: “objectively, X would be good if we did it, but for moral reasons of course (not X)”, which reads a lot like “we should do X but I don’t want to say that out loud so I’m just going to wink at it.”.

Dawkin’s full tweet, including subtext, reads like a bunch of coupled statements:

1.

2. I am willing to say this kind of thing in public

3. if you disagree that it wouldn’t work in practice you are dumb

4. you should also be willing to say this kind of thing in public

5. I want people who listen to me to see this statement and believe it a reasonable thing to say

6. I know people will be offended by talking about the merits of eugenics

7. and I want to offend them

8. my stance is all about facts, and people who disagree with my stance are disagreeing because their ideology is blinding them to facts

etc.

I think camp #2 is right because statement (1) is correct and obvious and pointless arguing about, and statements (2) through (8), etc are increasingly repugnant and awful. And I think camp #2 is just kind of bad at expressing this idea, but they’re right, because discourse on the internet is more toxic than ever due to, among other things, ‘rational’ people making sure that facts get all the airtime and credibility, and that having moral opinions about what is OK is increasingly regarded as irrational, ideological, and inappropriate. And in reality moral opinions (which are called ideologies by… detractors) are what makes the world good to live in, and doing things strictly because they are factually useful is what makes the world terrible to live in. (But that’s just my moral opinion, I guess!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

People in camp #1 aren’t “missing the point” in terms of not understanding where camp #2 is coming from; we just have different beliefs about what the political background is. Some examples:

A) Most people in camp #2 believe that alt-right ideology is a dangerous, growing, infectious threat; most people in camp #1 believe alt-right ideology has no real political influence, and that camp #2 is in the grips of a moral panic.

B) Most people in camp #2 believe Trump won because of misinformation on the internet; most people in camp #1 believe Trump won because the Democrats ran a weak nominee.

C) Most people in camp #1 believe the left has turned away from liberal values in recent years, and that there’s a real danger to public discourse from people in camp #2 trying to suppress ideas they don’t like. Most people in camp #2 believe that’s just a bogeyman invented by right-wingers who want to say racist stuff.

Different beliefs about the political background suggest different ways of reacting to Dawkins’ tweet (to some extent; I think even most people in camp #1 think Dawkins is an annoying edgelord.)

LikeLike

Your descriptions of these camps are sort of… caricatures, and don’t map cleanly to what I was talking about, since I was just describing two camps of “how do you parse Dawkin’s tweet?”. For instance plenty of people (myself among them) don’t per se think that alt-right ideology is an infectious threat, mostly because it is farcical. But it is still easy to see that Dawkin’s post has a bunch of subtext that is considerably weirder than its face-value claims. The debate here is over whether we should be taking claims at face value on the internet. A lot of us think the answer is a resounding No, and that people are weaponizing this kind of thing — “at face-value this sounds fine, so you can’t criticize me”. Sure we can, no one here is confused about what you’re doing.

People in my camp #1, like the author of this blog post, are absolutely missing the point, considering they’re writing blog posts defending a bunch of pointless stuff and not contributing anything to the conversation that actually matters, like reconciling this clash of interpretations.

LikeLike

This, and also… we should take into account that this debate is rooted in the UK government’s employment of someone who had previously said, very calm-and-rational like, that eugenicist policies – the kind that “everyone” agrees are bad – would be good actually.

“Everyone” in quotes because when some people say “oh of course *everyone* agrees that would be bad, we don’t want THAT,” they are in fact being disingenuous. Or outright lying.

I don’t want to come out blaming Dawkins *too* hard because it really is impossible to know all the context all the time but I think being aware that the problem here – the thing people are *scared of* – is a bunch of ruthless technocrats telling them they need to be sterilised for the Greater Good using a linguistic tone of [scientific, rational, numerical, professional-managerial]. And Dawkins should be aware that that is exactly the tone he writes in, and the position he adopted is not a neutral one in this particular debate because “extremely dangerous position masquerading as scientific neutrality” *is one of the positions*. I don’t think people are being stupid and misinterpreting him – they’re being *smart* and misinterpreting him, because he’s out of step with the deeper discussion.

LikeLike

If “Camp #1” possibly opens the way for trolls to push objectionable viewpoints couched in “facts”, “Camp #2” unfortunately opens the way for “emperors with no clothes” to go unchallenged because statements of simple facts are heavily tabooed.

LikeLike

I think the issue is that people follow this reasoning:

*a statement was made

*the statement could have been inspired by several different subtexts

*some of those subtexts are Bad

*if I do not strongly criticize this statement and those who made it, others could interpret me as ~not~ considering those subtexts to be Bad, and possibly even conclude that I consider them to be Good

*therefore I must strongly criticize the statement and those who made it, regardless of what their actual subtext was, even if it ~were~ Good, because I consider not being thought of as Bad more important than anything.

LikeLike

There are also different interpretations of “works” (producing some particular type of results vs. producing results that are desirable). For instance, if we replace “eugenics” with “nuclear weapons”, I can think of three interpretations of “nuclear weapons work”:

1. Nuclear weapons do, in fact, blow things up. (This is uncontroversial in the case of nuclear weapons, because people have already blown things up with nuclear weapons, but one could easily imagine something similar where this is an open question.)

2. Using nuclear weapons will help win a war. (This seems more controversial than 1.)

3. Using nuclear weapons produces results that are overall desirable.

Options towards the bottom of the list are more controversial, and also sound more like “we should use nuclear weapons”. Options 1 and 2 could also have the implication that we need to watch out for nuclear weapons and oppose them more, though it seems a bit weird to use the term “work” in that case, and in the case of eugenics, many interpretations of eugenics are things that we should watch out for regardless of whether they produce results.

Some more thoughts:

• I’ve noticed some responses objecting to the idea that we can objectively determine what genes are good, and to the idea that the results of selective breeding are good, which could mean that people are interpreting the claim with a strong definition of “work”, or that people have different interpretations of whether evaluating which genes are good is part of eugenics (factor #3); either way, there’s a difference in interpretation between “can make changes” vs. “can make good changes”. (It’s not clear from his tweets if he only supports the weakest form of the statement—”can change things in roughly some direction (though possibly with huge side effects)”, or if he supports some stronger form of the statement but objects to eugenics for different reasons.)

• The tweet reminds me of something that I thought about saying back in high school in response to a hypothetical creationist who assumes that people who are pro-evolution are pro-“social Darwinism” (≈ eugenics), namely that evolution just says that social Darwinism might work [I was using the weakest definition of “work” there], not that it’s a good thing… my point being that I was anti-eugenics, and that this wasn’t incompatible with believing in evolution. One interpretation of Dawkins’ tweet was that he was trying to make a similar point. On the other hand, this was over ten years ago, and creationism hasn’t been as relevant in the past several years as it was then; on the other other hand, Dawkins made a big deal out of being anti-creationist, so he might still be hearing from creationists even if the rest of us aren’t.

• Like in your previous post, I think part of it has to do with different assumptions about what positions people have that are relevant to argue against. If one assumes that the weakest interpretation is generally considered true and not being challenged, they might assume that he must be talking about a stronger interpretation; perhaps he’s still arguing against creationists who don’t even believe the weakest interpretation and a lot of other people don’t realize that (or perhaps he misinterpreted someone else’s objection to a stronger interpretation as a weaker interpretation). Likewise, how common one thinks a fully pro-eugenics position is will affect whether one thinks that Dawkins being pro-eugenics is a good interpretation of that tweet.

• I don’t think that everyone involved agrees with your assessment that eugenics is “not even close to happening”, especially if people are worried about some broader interpretations of eugenics that are still bad (e.g., cutting welfare for eugenics-related reasons is probably politically viable enough to worry about, since there are also people who want that for other reasons).

• If people think (correctly or not) that there are a lot of people who are pro-eugenics (for some undesirable interpretation of “eugenics”) but trying to obscure their position by arguing for something weaker, then even making the weakest claim with a disclaimer about how the person isn’t actually supporting eugenics can seem suspicious. (I think this might apply to decoupling vs. contextualizing in general.) Also if people think that lots of secretly pro-eugenics people exist, that would affect their assessment about how likely eugenics is to actually happen.

LikeLike

The biggest problem of eugenics is the kind of people which interest most about it (reichwinger sociopaths). Another problem is to believe all eugenics possibilities can be used without ponderation. Eugenics, at priori, is not bad or good. Used by the right people it can eliminate dark triad personality.

LikeLike

We don’t need to transform humanity into a Frankenstein. Just eliminate sociopaths (parasites and predators) would fantastic

LikeLike