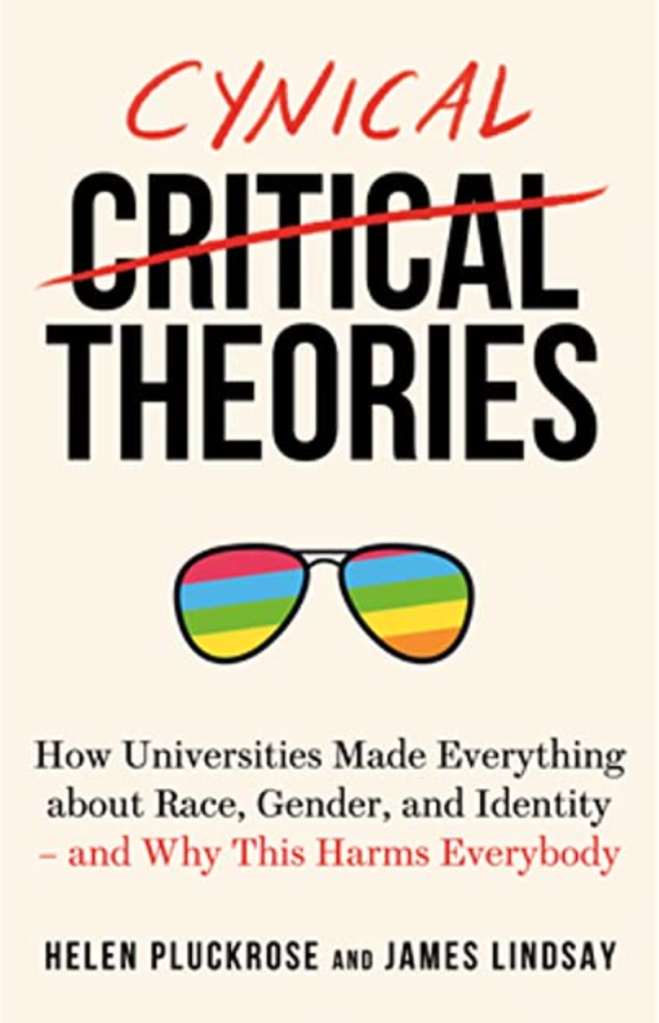

Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay, authors of Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything About Race, Gender, and Identity — and Why This Harms Everybody made a name for themselves in the fall of 2018 when they revealed that they, along with philosopher Peter Boghossian, had spent over a year writing and submitting, with some success, fake and ridiculous papers to a number of scholarly journals in certain branches of the humanities. They did this in order to demonstrate ideological corruption and low scientific standards. In their telling, the story goes:

Something has gone wrong in the university — especially in certain fields within the humanities. Scholarship based less upon finding truth and more upon attending to social grievances has become firmly established, if not fully dominant, within these fields, and their scholars increasingly bully students, administrators, and other departments into adhering to their worldview. This worldview is not scientific, and it is not rigorous. For many, this problem has been growing increasingly obvious, but strong evidence has been lacking. For this reason, the three of us just spent a year working inside the scholarship we see as an intrinsic part of this problem.

Because they referred to these fields with the umbrella term “grievance studies”, the hoax became known as the “grievance studies affair” — or alternatively as “Sokal Squared”, referencing the time in 1996 where physicist Alan Sokal got a nonsensical paper published in an issue of the cultural studies journal Social Text. It soon became clear that their hoax was only one part of a multi-pronged offensive against the grievance-studies-industrial-complex, as Pluckrose and Lindsay were working on a book together.

I read Cynical Theories when it came out in august 2020 and I’ve been wrestling with this review on-and-off ever since. “I’ll better get this done quickly, while the book is ‘hot'”, I thought. Hey-ho. At this point I’ve been messing around with it for so long that I can no longer tell how coherent its narrative is. My apologies if this is all over the place. I tried.

Also, before I get into it I should be upfront about my own ideological stance. I share the authors’ views for the most part, I’m sympathetic to their project, and that will of course color my review. Caveat lector. On occasion I will sound slightly ranty.

•

Part 1

The P word

The word “postmodernism” plays a major role in the book. It’s a multifacated term, popular punching bag, and probably voted “most likely to confuse and obfuscate” at the Big Words Festival of ’08. It’s on one level a forced label for a disparate set of thinkers who fiercely resisted labeling themselves or identifying with a movement, and on another level a more general word for a cluster of philosophical and political leanings (see my post on The Pomoid Cluster). It doesn’t exactly help that it’s also gone through a lot of change over time.

After some introductory words about the current cultural moment, Pluckrose and Lindsay go on to describe the evolution of “postmodernism” from the 1960’s to today. They split it into three phases, calling the first “high deconstructive postmodernism”, the second “applied postmodernism”, and the third and final one “reified postmodernism”.

The high deconstructive phase used complex, high-minded philosophy to undermine naive and unreflective trust in objective knowledge and the institutions that supposedly discovered and promulgated it[1]. Earlier philosophy’s apparent failure to construct objectively correct descriptive language helped to further problematize the notion of a stable meaning of terms, which facilitated an academic shift from focusing on language’s relationship to reality towards its function in negotiating social relationships. This postmodernism was highly self-aware and cognizant of its own limitations, and thus tended towards an uneasy mix of existential despair and nihilistic playfulness[2].

The next step and the next generation the authors refer to as “applied postmodernism”, where conclusions from the first phase were used as a jumping-off point, to further develop and justify theories around the creation of “knowledges” — plural — whose validity were dependent not just or even primarily on their fit with an objective reality but on things like the gender, race, class, culture, sexual orientation, or disability status of their users. Terms and methods of social constructionism were also brought in, even though they had been developed separately from high deconstructive postmodernism.

The final phase was “reified” (meaning “made real” or “made into appearing real”) postmodernism. What had earlier been abstract philosophical theorizing and methodological frameworks for exploring social issues and engaging in activism now became more like taken-for-granted ground truths about how the world works[3].

•

That’s not real postmodernism

In the authors’ story, as postmodernism evolved it devolved. It became less high-minded and less subtle. It eased up on the impenetrable jargon its earlier iterations had been known for. It got more concrete and more activist. By the 2010’s it had turned into something more like an orthodoxy than the sophisticated, contrarian nihilism of the early days.

The faith that emerged is thoroughly postmodern, which means that, rather than interpreting the world in terms of subtle spiritual forces like sin and magic, it focuses instead on subtle material forces[4], such as systemic bigotry, and diffuse but omnipresent systems of power and privilege.

It’s quite ironic how “pop-wokeism” (or “Critical Social Justice” in the authors’ parlance) — in essence a vulgarization of the already vulgarized great-grandchildren of high postmodernism — seems to have become so much of what its ancestor fought against[5]. Forcing reality into one ideological system that tells us what’s true and good and legitimate is precisely what early postmodernist thought aimed to destroy by picking its assumptions apart.

They describe this evolution as the result of deliberate choices, made to justify and make possible certain activism that one wanted to pursue, rather than of following the deconstructive logic to its natural conclusion[6]. The high deconstructives took their developed ideas seriously and applied their corrosive philosophy more consistently, but that breaks everything and won’t do if you want to achieve specific political goals.

This prompts the objection[7]: So their “reified postmodernism” isn’t actually postmodernism?

Yes and no, I guess. It reminds me of something I once read but can’t find again. It went something like (and is kind of key to this entire review):

Postmodernism is frequently simplified, vulgarized and turned into a strawman by its opponents. It is also frequently simplified, vulgarized and turned into a strawman by its proponents.

It becomes a semantic and philosophical debate whether vulgarized and distant descendants of ideas is still “the same” as the originals. Truth is, “postmodernism” is a big bundle and there’s a wide spectrum from more to less sophisticated and reasonable versions[8]. Using it opens the book up for a lot of criticism that they’re misrepresenting it or just don’t know what they’re talking about. I absolutely understand why many feel that way. “I, reasonable and sophisticated understander of X, am not the same as, and am not to be held responsible for, unreasonable and unsophisticated peddlers of something-like-X” is a normal and valid human reaction.

However, it often turns into “…and if you refer to something-like-X as ‘X’, what you’re saying about it is wrong and can be completely dismissed, regardless of whether something-like-X exists or not”. That’s less valid, and I think it, like other criticisms of the “good academic critical theory isn’t really like this” flavor, is beside the point Pluckrose and Lindsay want to make. The idea is not to take the strongest postmodern academic ideas and show that they are identical to, or imply, the most vulgar of vulgar wokeism. Instead they take the (manifest) existence of such vulgar wokeism as a given starting point and try to explain where it came from.

If that means simplifying scholarship, sometimes but not always to the point of butchering it, then so be it, I guess. It can be defended by noting that vulgar wokeism itself is the result of a butchering process — inside and outside academia.

Two principles and four themes

Let’s look at the simplified, core postmodernist claims that the authors put forward as a basis for the “grievance studies” fields:

The postmodern turn involves two inextricably linked core principles — one regarding knowledge and one regarding politics — which act as the foundation of four significant themes.

These principles are

• The postmodern knowledge principle: Radical skepticism about whether objective knowledge or truth is obtainable and a commitment to cultural constructivism.

• The postmodern political principle: A belief that society is formed of systems of power and hierarchies, which decide what can be known and how.

The four major themes of postmodernism are

1. The blurring of boundaries

2. The power of language

3. Cultural relativism

4. The loss of the individual and the universal

How true are these then? Woo-boy. The two principles are too abstract and general to be true or false as such. They’re not singular, concrete claims but whole systems of beliefs, attitudes, and priorities where some are quite true and others less so, and some are value judgments not about truth at all. They are precisely what I had in mind when I wrote about partial narratives five years ago. And that’s what they are, partially valid narratives, or frameworks, or schemas. Whatever. They’re ways to look at things, that capture some parts of the truth while ignoring others.

As such they’re good examples of correctives we sometimes should think about and take into account as a complement to standard Enlightenment principles. However, treating them as truths (beliefs whose opposites are false and can be dismissed) that can be used to derive further truths, is a major misstep[9]. Pluckrose and Lindsay argue, as I read them, that this is what happened.

The pop-woke gestalt

After telling their three phases story they present the relevant fields in turn: postcolonial theory, feminist and gender theory, queer theory, critical race theory, and disability and fat studies[10]. As presented — and this fits with the earlier impression I had of them, even though of course doesn’t prove it correct – calling them fields or scholarly disciplines is almost a misnomer. They’re at least as much defined by the social and political goals they’re trying to achieve as by the topic they study. Put more sharply, they’re ideologies that got themselves into a position to be considered scholarship rather than the intellectualizing wing of a school of political activism[11].

It’s hard to list the core claims of this ideological family in its academic incarnation, because academic ideas tend to be complex, detailed, the objects of vivid internal debate, and almost by design hard to summarize. The simplified pop-gestalt, however, I think can be spelled out, to the best of my ability in not so many words, as this: who we are, how we behave, and the society we make up are the results not to any significant extent of nature, chance, or individual agency, but of an ultimately arbitrary cultural system of categorizations and constructs that determine who we are, what we feel, think and create, based on our demographic characteristics. This matrix (sic) assigns us roles to play out and our personalities to fulfill them. It creates social inequality as some identities are assigned privilege and others oppression. The system doesn’t correspond to, depend on, or reveal any objective reality but simply persists through the inertia of socialization, constant repetition and rearticulation, especially supported by those on the benefiting sides of its inequalities.

In this “structural reductionist” view, it becomes a natural conclusion that if the system of categorization and hierarchy could be dissolved or reversed, aggregate inequities would disappear, and this dissolution or reversal (which one of the two depends) is the paramount moral imperative. Hence there is a radical spirit and a hostility to the existing, largely liberal social order. Appeals to that which runs counter to this story — the denied and denounced like nature, objective reality, individual agency and rights, or just about any competing belief or value system — are cast as nothing but the system and its beneficiaries spinning rhetoric to justify their illegitimate hold on society. Thus, dissent becomes not a matter of legitimate disagreement but simply an aspect of what’s supposed to be exposed and dismantled. The resulting distrust of open debate (remember “the power of language”; to speak is to exercise power, not to share or evaluate information) puts it on a collision course with enlightenment thought and the liberal democracy it created. It collides with science and meritocracy insofar as it evaluates claims and people based on whether they help the cause of dismantling the corrupt structure and not on correspondence to a supposed objective reality or on demonstrable skill.

Reduction to structure also serves to justify a dismissive attitude towards people’s desires, rights and dignity, since if individual wants are products of the system rather than the other way around, you feel less obliged to accept and respect other people’s preferences and opinions when they aren’t what you think they should be (“they’ve been brainwashed by the system”). That’s more or less a 180 turn away from liberalism — but I’m getting ahead of myself.

There’s of course more to it than this, and pop-wokeism is also a jumble of disparate, partially contradictory ideas. I focus above on the aspects that come from the kind of scholarship that Pluckrose and Lindsay discuss. You could say these ideas are simply imported and pasted onto more straightforward “chimp politics” dynamics and merely used, rather than forming the basis of a genuinely held belief system, and you’d have a point.

To take something and run with it

How do you get all the way to a radical conception of reality and society while maintaining at least the appearance of scholarly rigor? You pick ideas that have some truth to them and treat them as if they’re completely true. Then you keep going: the “applied” step chose to take ideas like the principles and themes as provisional truths and see what would follow — what could follow, and then the “reified” step took these as actual truths.

The methods involves overleveraging philosophical points that are in principle sound but with limited importance[12]. For example, saying that reality is socially constructed or that observations are theory-laden and thus depend on your background (favorites of constructionists on knowledge) is a bit like saying that “pain is just a subjective experience”, or using the existence of optical illusions to argue that observation can not be relied on to find out anything about reality. Technically correct in a sense, but doesn’t imply the things of consequence that’s suggested, for example that pain is a choice, unreal, or unimportant — or that knowledge is a complete creation of our preconceptions.

The philosophies suggested by taking such statements fully on board can turn out pretty weird. If you come to conclusions that seems absurd on the face of it — and here I’m thinking about considering two sexes and their differences being a purely cultural convention, scientific astronomy not being meaningfully different in an objective correctness sense from tribal mythology, or considering punctuality a facet of white supremacy — then rather than buying into that idea and push it, you could consider it a sign that something’s gone wrong in the reasoning process.

By what the authors tell us, it sounds like people with radical temperaments and convictions have done this — taken some basically reasonable but marginal corrections to enlightenment modernism and extended them further and further. They’ve then stacked more and more on top of each others’ theories until the table heaves with bold, grand claims, derived from a few kernels of truth and sometimes inflated with generous helpings of hot air.

For example (and this to the best of my understanding) a key element of pop-wokeism comes from standpoint epistemology, which says that your understanding of reality is shaped by your social experiences and position (alright), and that knowledge is dependent on your demographic identity (slightly less “alright”), and furthermore, that ostensibly oppressed groups have access to both their own perspective and that of the corresponding dominant group (e.g. men cannot understand women’s perspective, but women can understand men’s because they live in a man’s world). Here my “alright” is wearing quite thin. It’s easy to see how something like this can sometimes be true in a narrow, context-dependent sense, but also easily be overextended and used to dismiss any questioning at all of narratives pushed on behalf of those classified as oppressed.

You can’t blame academics all too much. Building on each others’ ideas and pushing them further is what they do and are supposed to do — it’s just that you run into problems when you theorize over things that are both abstract and vague, i.e. they aren’t tightly constrained by anything other than the intersubjectivity of practitioners — neither by physical reality like the technology-adjacent hard sciences, nor by the strict formalism of mathematics. If you at the same time lack the ideological diversity required to prevent the inevitable assumptions, simplifications, priorities, and generalizations from consistently drifting in a specific direction over time, the field will confuse their produced results with true conclusions about the world[13].

Ironically, it suggests the “grievance studies” fields don’t reject reason, as is often claimed, but instead rely on it too much. Yes, I’m lightly twisting the meaning of “reason” for a laugh, but I mean it in the sense of believing that just because you can produce a chain of argumentation for an idea it somehow compels people to believe it and to endorse its implications. It’s a bit like making abstruse theological arguments for the existence of God and, because all your peers are also theologians, expect them to be generally convincing[14].

If we combine this with the idea above that contemporary wokeness in many ways stand directly opposed to the ideals of early postmodernism — and much of what e.g. Foucault said about the production of what was considered “truth” and “knowledge” in his society applies very well to the woke-industrial complex of today — we can say with a not-quite-straight face that the problem with wokeism (or Critical Social Justice) lies in it being insufficiently postmodernist and too reliant on reason.

•

Part 2

Baby in the radical bathwater

While extreme when taken to their full logical conclusion, the ideas at the base of many of these fields can’t be dismissed as complete nonsense. It’s a core part of the problem that it’s hard to stand against wokeism at all without going (or be perceived to be going) far away to the other perceived ideological endpoint. I’d have wanted more discussion in the book on how to integrate the valid objections to liberal society into its framework so they can be properly counterbalanced (or “neutered” as I’m sure some hardline radicals would put it).

As a firm but moderate[15] anti-wokist I’m a little embarrassed when I see complete dismissal and overconfident mockery[16]. There is some truth to the constructedness of identity, categories, and language[17], to criticism of both modernist and colonialist arrogance and overreach, to the difficulty of drawing definite boundaries in the area of sex and sexuality (like everywhere), and to disabilities being partly a function of living in certain environments, physical and social. Et cetera. Really, even my simplified and unsympathetic description of pop-woke ideology above is not totally in the wrong. It captures a part of the truth about as much as other radical philosophies like anarcho-capitalism, fascism, and Kacynskian primitivism[18] do.

Radicals have something in common: they tend to point to legitimate problems, but you don’t want their solutions. Do listen, sometimes and somewhat believe, but don’t hand over the keys[19]. While some woke talking points deserve a hearing, the whole very much doesn’t deserve hegemony. By that I mean the adoption of its conceptual apparatus and newspeak (a very deliberate choice of word) as the background, “default” ideology of public life.

The default ideology

“Default ideology”? Well, “conventional wisdom” in different wording and with a less down-to-earth connotation. You could summarize Pluckrose’s and Lindsay’s worries by saying that right now, Critical Social Justice is installing itself as the standard point of view in educated circles — the line you’re implicitly expected to toe as a well-educated, well-socialized middle class person. It’s doing this by establishing a dominant presence in universities, media, corporations, education, and civil service.

I feel the book could use a more detailed discussion of the methods used to acquire this kind of institutional power[20], and how it depends on widespread lack of awareness regarding the the philosophical underpinnings of some of these ideas. You could say that nice-sounding but vague progressive language offers a way in for more radical stuff: a place on the cell for the virus to hook on to, as it were. I didn’t pull that unflattering virus image out of my rear, and nor did the authors. They cite a feminist scholar using such a metaphor to describe a suggested strategy of spreading ideas.

Now hold on for just a minute. Is woke posturing by big corporations, cultural sensitivity training courses and workplaces and mandatory diversity statements in universities really a plot orchestrated by radical academics hell-bent on overthrowing the liberal social order by calling its distinctive features “toxic patriarchial whiteness supremacisticixm” or whatever the latest mot-du-jour is that lets everyone know you’re with it?

Not exactly. Pluckrose and Lindsay don’t think so either.

Fortunately, it is unlikely that the majority of people—let alone corporations, organizations, and public figures—really are radical cultural constructivists, with postmodern conceptions of society and a commitment to intersectional understandings of Social Justice. However, because these ideas offer the appearance of deep explanations to complicated problems and work within the Theory, they have successfully morphed from obscure academic theories—the sorts of things that only intellectuals can believe—to part of the general “wisdom” about how the world works.

In other words, low-level background Default Ideology. Hegemony. An ideology doesn’t necessarily need the whole of or even a majority of society to believe in it to gain control, it just needs people to affirm it in public enough due to fear of consequences if they don’t. This isn’t a hypothetical scenario. Preference falsification is a pretty well-documented phenomenon.

There isn’t a hidden cabal with a grand plan; everyone involved have their motives, their beliefs, and their interests. I’m sure there are some radical theorists that do fully believe in their own aircastles, some that don’t believe as such but think they have some validity and thus push for them in the face of what they perceive as a stonewalling society, some unsophisticated blind followers[21], some out to make a buck, and some “crude activists” (the political version of football hooligans, basically, who are into things that let them fight and feel powerful) that don’t care about all the elaborate intellectual justifications but simply grab onto what helps them do what they want to do[22].

Nonetheless, it can all add up to mimic intentionality if you think of all the different groups playing their parts in a system with its own logic and apparent goals. You might say that while people aren’t conspiring per se, that isn’t necessary for them to take part in a structural or systemic conspiracy.

Disrupting the system through divide-and-conquer

Pluckrose and Lindsay are trying to disrupt the system. They’re doing it by trying to alert and persuade a particular group with their book: the unaware, lukewarm wokes. They’re the ones who mouth the words of wokeism because they don’t know about their radical origins, consider the loudmouth vanguard (if familiar at all) atypical and unimportant, and see the slogans as no more than a natural expression of sympathy for the weak and oppressed, all in perfect concert with liberal values.

This target audience think of themselves as liberals because that’s what nice, open-minded people are supposed to be. With that basis for a political identity you don’t necessarily have strong reactions to things coming up and looking superficially like what you’ve come to know as liberalism but lack some of its core features like individualism, universalism, due process, and dignity culture[23]. Given that, there’s no reason apparent to them why importing woke ideas and language without explicitly liberal guardrails and counterweights[24] could be a bad idea.

In the beginning the authors mention that precisely because wokeism or Critical Social Justice is seen by many as continuous with liberalism, it becomes especially difficult to speak out against as a liberal. The whole rest of the book can be seen as an attempt at making this easier by highlighting the discontinuity — and by doing this they’re trying to split the coalition between dedicated wokeists and oblivious, well-meaning liberals.

They want warn the second group (or at least give anti-woke liberals the means with which to warn and convince them) that what appears unobjectionable is in fact continuous with an agenda that easily lends itself to overreach and power accumulation in the hands of scolds, busybodies, and wannabe totalitarians. They present it as clothing itself in the skin of liberal progressivism but identifying racism/sexism/colonialism/ableism/transphobia/fatphobia etc. as essential features of modernity and the Enlightenment, which can serve to justify almost any attack on, or bypassing of, central features of the liberal order in the name of fighting them[25].

So? Is that so wrong? Is Enlightenment liberalism holy?

The authors have been criticized for taking the correctness of liberal values for granted. I guess you can say that they do, but I think they’re counting on getting away with it. I think they’re counting on liberal principles not being seriously in question by most people, and if forced to choose a comfortable majority would retain them over woke ideology. They’re saying — yelling at the top of their lungs, in fact — that we do have to make that choice. They assume, trust, or hope, that people will agree with them about the answer. I don’t know if they’re right, but I hope so.

•

Part 3

A new background faith and a second secularism

At points Pluckrose and Lindsay call CSJ a faith, and it’s not by accident. It’s a trope by now but the parallels to religion really are striking. It’s not just that it has pretensions to being “general wisdom about how the world works” the way Christianity was for such a long time in the west. It has statements of faith, communal rituals, its own concepts of sin and submission, hostility toward other ways of making sense of the world, ideas of original sin and need for cleansing and repentance, a full merger of the descriptive and the normative, and insistence on its own relevance to everything in society and thus entitlement to influence everywhere.

You might even point to how the pipeline from ivory-tower scholars developing abstract theory that gets simplified (but with preserved authority) and used by plebs to control other plebs is similar to medieval church dogma being worked out by (literally) cloistered scholars and then promulgated through the preaching of simplified maxims and rules to the populace by middlemen priests — today educators, activists, journalists, and HR officers.

And just like religion we have many, perhaps a majority, that pay lip service but don’t necessarily believe it or take it all that seriously. To those, alarmism like Pluckrose’s and Lindsay’s can sound hysterical the way some atheists’ complaints about religion might sound to merely nominal Christians. “Eh, what’s the harm? It’s just basic morality. Those who take it too seriously are a small minority without any power, right? People who want religion to have real power over society don’t represent me, and agreeing to swear on a bible (or include my preferred pronouns in my bio) doesn’t mean endorsing the values of hardliners.”

Well, some of us think it does. Or at least we have no reliable way of telling when it does and when it doesn’t. Some of us don’t do lip service (like some of us don’t eat meat, drink alcohol, or have sex before marriage) and think mouthing the words and affirming the symbols constitutes unconditional submission, to thought systems with hegemonic ambitions and the people that act as their representatives. And we have exactly the same creeped-out reaction to both Christian and woke varieties. They feel the same, and I’m not just saying that for rhetorical effect. They really do (and that makes it feel extra chilling, in a pod-person sort of way, when outspoken atheists push wokeism). This applies even when the symbols aren’t explicitly intended to mean much; “it’s just boilerplate” is itself a major sign of hegemonic status, and mere symbolic submission is still submission, just in advance.

Say I would be joining a company where perhaps nobody demands that I wear a cross or participate in morning prayer, but I’m calmly told that at this company we support family values and the sanctity of human life. Alright… that sounds pretty unobjectionable when taken literally, I guess, but why those things in particular? What am I agreeing to?

For a real example, I read an ad for job a while ago that I decided to not apply for (for other reasons). I noticed the language at the end of it about how it was “a workplace committed to diversity and inclusion” and some further such phrasing. Did I expect this place to be full of radical wokeists? Not really, and nor do I mind the literal, liberal meanings of “diversity” and “inclusion”, quite the opposite. But these terms carry connotations — active links to the paradigm that owns them — and using them in particular (instead of engaging in visible diplomacy by, for example, using other language for the same things[26]) is a choice that leads me to believe there’d be a cultural and social environment that recognizes no potential problems with, or hard limits to, ideas in this space.

Against this view stands lukewarm wokes’ feeling that woke ideology is just liberal niceness (and who could be legitimately opposed to that?) which is just like lukewarm Christians feeling that Christianity is just compassion and morality (and who could be legitimately opposed to that?). Are they right? Am I and others like me overreacting? Maybe. In one sense of the phrase it’s true that this is all in the mind of me and others who feel the same, and the question of how justified the unease is escapes easy answering. Perhaps most of the time there’s little to worry about and viewing things as demeaning and threatening is in large part a ~choice. But you don’t know, because without visible ambivalence, balancing, or acknowledgement that you can go too far, there’s a clear implication that there will be no resources — no understanding, no “cultural infrastructure” — in place to resist overreach.

So while I didn’t expect the place to be full of radical wokeists, I did expect it to be full of people who couldn’t be trusted to not side with them, if push came to shove. Does that count as a serious problem? Opinions differ, I’m sure. To me it’s at least serious enough to complain about in a blog post[27].

We do have a social technology to deal with this kind of situation. It’s called secularism and it consigns religious matters to the private sphere. It’s a cornerstone of modern pluralism, freedom of conscience, peace, and diversity (sic) — and an all-round great idea. Pluckrose has argued elsewhere that Critical Social Justice ideology is similar enough to religion in the kind of role it plays in many social environments that we should apply the principles of secularism to it.

I really missed more of this discussion in the book, since I think extending secularism (the reasons it’s a good idea applies to more than religion) is the key to combating social pressures towards both religious and ideological conformity. Part of me thinks this should have been the framing for the entire book.

•

Translation and transparency

To sum up: Pluckrose and Lindsay are concerned about Critical Social Justice gradually making itself the conventional wisdom of educated people and their institutions, if not necessarily in substance then at least in symbolics. To prevent this they’re trying to highlight how it’s different from the liberal progressiveness it often looks like, and by doing this they’re trying to make it easier to dissent from a liberal point of view. They point out how it’s not basic broadly agreed-upon morality and scientific scholarship, but rather a particular ideology in many ways reminiscent of a religion, and thus ought to be treated like one.

It’s vital to be credible in this project. In the beginning they say they want to be translators or interpreters of Critical Social Justice theories (Lindsay runs New Discourses which includes a Translations from the Wokish encyclopedia), and this is a bit hard to square with having as obvious an agenda as they do. They try to make their case well with plenty of quotes and citations etc[28], but I’m not sure it’s sufficient since it’s quite easy to believe they’ve been selective in their choices or uncharitable in their interpretations. I’m virtually certain such a case can be made, but I’m not as certain how strong and significant it would be.

I’d have preferred that they’d spent more words on directly acknowledging and addressing the objections of those who don’t recognize themselves in their descriptions of CSJ. Many think of themselves as supporting Social Justice and also believing in science and individual rights. I think more handholding there would have been appropriate, including admitting that there are more benign and neutered versions of some CSJ ideas and in practice the discontinuity between liberalism and Critical Social Justice is papered over in a rather complex way by ambiguities and reinterpretations, making things less clear cut than they appear in this book.

With a more worked out notion of “extended secularism” and a fuller treatment of the complex dynamics between intellectuals, radical activists, and the lukewarm wokes this could have been a mighty tome — a critical-of-critical-social-justice-theory omnibus instead of the relatively slim volume that it is. I do think the book is mostly successful at what it sets out to do: create a rallying flag for anti-woke liberals and give them somewhere to point their on-the-fence friends. It’s just that with a totally unreasonable amount of additional work and time it could have been even more rewarding for me personally. Waaaah.

•

An ending with a call to arms and for a renewed liberalism

They end with a few campus horror stories of what happens when this stuff is put in the hands of young activists eager to find a grindstone for their axes, a source of meaningful righteous struggle, and an opportunity for the intoxicating experience of personal power. Their targets have little chance to defend themselves when the chanted slogans have already been agreed upon and put into place as policy, with little to no protection against overinterpretation or abuse. If all the verbiage above boils down to a single message, it’s this.

According to Pluckrose and Lindsay, a renewed liberalism with both ears and a spine is required. It must deal with the remainder problems of Enlightenment thought while standing strong and confident enough to affirm that liberal society and it’s core value of individual equality under the laws, norms, and processes is not a corruption and not a problem to be dealt with.

And I think a strong case can be made that liberalism does deserve to be the norm (somebody who just straight up rejects this is hard for me, or the authors I believe, to have much meaningful dialogue with). Pardon me for getting overly dramatic here by the end, but whenever in the modern era trust in liberalism was lost the consequences have been disastrous. In a way the rise of wokeism has exposed a vulnerability in contemporary liberal ideology — a security hole that needs to be plugged, if you will. We have successfully, but at a tremendous cost, been immunized against nationalist radical collectivism, and partly against traditional class-based such, but this is another attack vector, one that exploits the latent guilt of the privileged middle and upper classes and our intuitive, automatic sympathy for the disadvantaged.

Complacency from mainstream liberalism doesn’t cut it when history is no longer ending. Pluckrose and Lindsay have written this book with the aim of shaking some life into it’s well-fed, couch-potatoish body by pointing to CSJ/wokeism as foe, not family. They don’t do it perfectly but well enough, I think.

• • •

Notes

[1]

This meant something rather different in the 1960’s compared to what it means now.

[2]

This is kind of the “postmodern mood”.

[3]

The description of the reified turn brings to mind the rhetorical strategy of not arguing for what you believe, but rather for things that already assume what you believe, as if it’s a recognized fact. If I say B, which relies on A, you can’t even discuss B without at least provisionally accepting A. That “provisionally” quickly becomes “actually” unless you actively resist it, if not in your mind then in the social environment. Otoh, if somebody rejects A you then accuse them of not engaging with B. There’s an example in the book from a gender studies class that stood out to me, although it’s not described in these terms.

[4]

I don’t think these are quite as “materialist” as they say. They’re not supernatural, but they’re based on concepts, thoughts, symbols and discourses, which are assigned great causal powers. These are immaterial in the sense that they’re abstracted and framed in thought-language (rather than matter-language) and work according to principles entirely divorced from the mechanisms of material causation.

[5]

This touches on a point I haven’t gone into in this article, mostly because it deserves its own article (or its own book). Much of early postmodernists’ critiques of science and expertise as an institution sits in an awkward place with respect to pop-wokeism, due to its strong position in the intellectual establishment. Instead a lot of it has been taken up by the right — or is now suddenly coded right-wing in a way it wasn’t up to very recently (e.g. vaccine skepticism or alternative medicine used to be weirdo-lefty things until, like, last Tuesday).

According to the psychologist Keith Stanovich:

In the 1960s and ’70s it was viewed as progressive to display skepticism toward these groups of experts. Encouraging people to be more skeptical toward government officials and journalists and universities was considered progressive because it was thought that the truth was being obscured by the self-serving interests of the supposed authorities listed on current “expert acceptance” questionnaires! Yet when conservatives now evince skepticism on these scales, it is viewed as an epistemological defect.

[6]

This all raises a point about their decision to use the term postmodernism in relation to woke ideology. Their modifiers (“high”, “applied” and “reified”) shows they know the problems, but those easily fall away in the discourse surrounding the book, and perhaps another term altogether would’ve been better. A slippery, ambiguous term can be a resource (albeit suspect) or a liability, and in this case I think it’s a liability.

[7]

It does not “beg the question”.

[8]

To quote David Chapman:

In the 1970s and 1980s, the best postmodern/poststructural thinkers presented meta-rational views, based on their thorough understanding of systematic rationality. This first generation of postmodern teachers had a complete “classical education” in the humanities; they mastered the Western intellectual tradition before coming to understand its limitations.

Deconstructive postmodernism, their critique of stage 4 modernism/systematicity/rationality, is the basis of the contemporary university humanities curriculum. This is a disaster. The critique is largely correct; but, as Kegan observed, to teach it to young adults is harmful. Few university students have consolidated rationality. Essentially none are ready to move beyond it. Pointing out its defects makes their developmental task more difficult.

I.e. to truly absorb the valid messages of postmodernism you have to first internalize modernism well enough to be able comprehend its limitations. If you get to hear the critiques first, they risk being used to justify rejecting modernist/systematic thought entirely and remain in a pre-systematic mindset.

[9]

Part of the reason is that academics are incentivized to say counter-intuitive things. Otherwise, of what apparent value is their expertise?

[10]

They discuss their agendas with some quotes and citations. I cannot know how fair or correct these descriptions are. I don’t believe they’ve picked the most representative examples, rather the ones most similar to and most inspiring of contemporary vulgar wokeism, which will obviously affect how they come across.

You could (and some do) argue that the authors overinterpret quotes and citations to make it seem crazier. I keep that possibility open but I’m not convinced, because most of the politically desired (and frequently pushed) implications don’t follow unless you both take the postmodern principles too far AND apply them selectively. Reasonable interpretations, or political force — pick one. Different people make different picks, which makes it hard to criticize and easy to criticize the criticism. It’s no accident that the “motte-and-bailey argument” concept was first applied precisely to this family of ideas.

[11]

I readily admit it’s hard to draw a sharp line between what is and isn’t political. When you get further away from hard science, the question of how to set up your conceptual apparatus becomes more and more subjective (you need to compress away much more detail), and such choices do by necessity become political in some sense when they concern human social affairs. This is a totally valid point. Instead of using this as an excuse to be as slanted as you want, however, it ought to make us more concerned about minimizing the influence of personal politics in scholarship, for example by aiming to make fields as politically diverse as possible to prevent them from turning into ideology factories.

[12]

Similary we could, for example, take the fact that we can’t philosophically justify logical induction (using past experience to predict future outcomes) very seriously and use it to reject all knowledge whatsoever as arbitrary and unreliable. The problem is that a lot of knowledge seems pretty reliable indeed, so something is clearly wrong with that. If you could use that one for political gain as readily, many people would find it convincing all of a sudden — and because it’s strictly true it wouldn’t be trivial to defend against.

[13]

Note for example that “woke” means something like “suddenly aware”, as if it signifies becoming enlightened and seeing things the they way they really are, as opposed to having bought into a specific ideology that sees the world from a very specific angle and denies the legitimacy of others.

[14]

This sort of thing feels like a slam-dunk for those who want to believe, but is completely unimpressive to others. This is frustrating and rage-inducing, which I suppose reinforces radicalism and an impatient, hostile attitude.

[15]

I’ve gone back and forth over whether this should say “firm but moderate” or “moderate but firm”. My ambivalence over the wording mirrors my ambivalence about the ideas themselves, since I flip between thinking of the limited, humble, and reasonable versions vs. the vulgar and batshit ones as the central examples.

[16]

Pluckrose and Lindsay certainly differ in their preferred strategies, if we judge by their communication styles on Twitter. Lindsay plays the role of a fully committed culture warrior, refusing to seriously engage or give a single nanometer. He prefers instead to fight vulgar wokeism with hard resistance, mockery and disdain, in my reading motivated by a complete lack of trust in the other side engaging fairly in the first place, and a belief that the best way to resist woke power and inspire others to do the same is to loudly, aggressively, and performatively refuse to be intimidated by it. Pluckrose, on the other, hand acts like a beacon of charity and rationality, persisting in engaging in good faith with people even to the occasional detriment of her own well-being. I’ll give you one guess which one of them has the higher Twitter follower count. Part of me wonders if they’ve taken on these opposite roles on purpose to appeal to a maximally wide audience between the two of them (but I’m not claiming that).

[17]

God knows I go on and on about language and why it’s not trustworthy on this blog.

[18]

Could you create a family of disciplines working to apply Kacynski’s worldview to everything in society and thereby render it Respectable and Scholarly in the same way? Yes you could.

[19]

The same advice applies to radicals of other political persuasions as well, like hardcore libertarians or populists.

[20]

Tactics include creating committees (to fight supposed sexism/racism/etc. that are said to be everywhere at all times), institute positions, adopt codes of conducts and policies where their specific language is used, with the requisite exploitable ambiguities.

[21]

Many are likely not radicals by temperament exactly, but more like hungry 19-year-olds who are totally into this stuff because it’s the first full-throated ideology they’ve been exposed to. It makes me think of this quote by Robin Hanson:

“Philosophy is mainly useful in inoculating you against other philosophy. Else you’ll be vulnerable to the first coherent philosophy you hear.”

I tend to think the more philosophies you’ve been exposed to and internalized, the less fervently you believe in any one of them.

[22]

Many (perhaps most) people don’t need justifications beyond what sounds and feels good and helps them politically and/or personally. Thus many don’t know the all underlying philosophical ideas and don’t realize they’re kind of required to support all the far-reaching claims of oppression. “Academics say what I want to believe and helps me amass political capital” can be quite enough to consider matters settled, and dissent uneducated, ignorant, and perhaps hubristic.

[23]

This blurriness is likely particularly common in the United States, where liberalism (incrementalist, individualist, dignity- and agency-focused) and leftism (radical, collectivist, structuralistic) aren’t as clearly differentiated from each other the way they are in Europe.

[24]

Incidentally, the resource set up and headed by Pluckrose for supporting people who object to CSJ ideas taking hold at their workplaces and such is called Counterweight.

[25]

When these concepts are understood in their traditional, liberal senses by those “not in the know” it makes them seem like different, more empirically far-reaching claims than they really are. Ordinary center-left, lukewarm wokeness is in many ways a hybrid ideology, where concepts from one context is reinterpreted and integrated into another and given partially different meanings (e.g. “everyone is racist”). I wrote in Erisology of Self and Will, that a kind of hard, sinister genetic determinism results from grafting bits of sciences with bearing on the mind (like evolutionary psychology, behavior genetics and cognitive neuroscience) onto normal, commonsensical beliefs about it.

[26]

For example I write “note”, “content note”, or “content warning” instead of “trigger warning”. That sort of thing enables you to go along with something you think is valid but not import a piece of jargon that has a bunch of friends you might not want around the house. It’s yutting.

[27]

I focus on this perhaps-less-pressing-in-the-grand-scheme-of-things perspective because it’s the one I feel most qualified and motivated to explain, but there are other and more consequential issues. Besides generally encouraging belligerence and the problem of subjecting institutions (science, education, public authorities) to highly particular orthodoxies rendering them less effective and trustworthy, the woke eagerness to essentialize race comes off to me as especially reckless. Modern democracy owes much of its health to a long process of deemphasizing subnational tribal and ethnic identities to keep coalitions fluid and thus politicians responsive to public opinion, as well as prevent elections from descending into a spoils system.

[28]

It’s a little peculiar that they don’t directly and preemptively respond to the inevitable accusations that they don’t understand what they’re attacking by bringing up the Sokal Squared Hoax and arguing that they got papers published which supposedly shows they do understand it well enough. It probably wouldn’t make much difference to critics, but it would still be a defense. Perhaps they wanted to distance themselves from it for some reason?

Did you enjoy this article? Consider supporting Everything Studies on Patreon.

Footnotes 4, 14, and 26 exist, but the links to them from the text are broken.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, I’m on it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Although I’m not sure reading Pluckrose and Lindsay’s book would be the greatest use of my time at the moment, I found your review of it interesting and enjoyed a number of your insights (such as [11], which I had never thought to frame that way!) on the issue of “woke ideology”. Here are a few stray thoughts:

Although I haven’t looked much into Pluckrose’s work (I have seen an interview or two with her on YouTube and had a look at some of the articles in the Sokal project), I’m glad to hear that she’s framing the issue as a sort of absolutism in need of a “counterweight”. This is an example of exactly what I was aiming for in several of my WordPress posts, particularly the ones about not dismissing gadflies.

It’s telling that on first reading of this passage for a moment I misread the phrase “while people” as “white people”. I think this “Freudian slip of a misreading” points to the fact that the more sophisticated woke ideologues seem to understand, recognize, and even emphasize the general phenomenon of “not conspiring per se, but still taking part in a structural or systemic conspiracy” when it comes to, say, white people participating in structural racism (“We’re not saying that white people go around deliberately trying to keep people of color down, just that on a number of different levels everyone is playing their part, mostly out of self-serving but non-malicious motives, in a system that does”).

My first major experience with this was back quite a few years ago, I think most likely in 2014 in the wake of the Roger Elliot massacre when pop feminism was at the helm of Social Justice ideology. A (male) Facebook friend wrote a profusely contrite status about how he (like literally every other man in the world) had no idea or perception of the difficulties women face so he (like every other man in the world) needed to repent. As far as I recall, he didn’t list any concrete sin he had committed or even a particular misconception he had held, but he did literally use the word “repent”. Who was this acquaintance? The president of the atheist club at my then university.

Or, maybe nothing should be read into language like that at all, as it’s become so ubiquitous in certain sectors (at least where I am, in the US) that I’m beginning to suspect it’s just a set of phrases that people chant (to continue the religion metaphor) without much deliberate ideology behind them. I’m currently on the academic job market and looking at job advertisements at dozens of universities. Just about each and every one of them includes some variant on that phrase: “…in accordance with our mission of diversity and inclusiveness”, “this university is committed to the values of diversity and inclusion”, etc. Sometimes it’s a whole paragraph of such flowery language. Sometimes that whole paragraph is the first paragraph of the job announcement, before a description of the job is provided. Often the choice of phrases and timing conveys to me a sense of proudly proclaiming that their university is special or original or superior to most others for making diversity and inclusion a priority, as though every other job announcement at every other university weren’t saying almost the exact same thing word for word… but I digress. My point is that if it’s practically mandatory to extol this value, then virtually nothing can be inferred by it.

Yes, I’ve always done the same (and having started out the world of Tumblr before I was ever on WordPress, I issued content warnings a lot more liberally, especially in my earlier days of blogging). I’ve never been comfortable with appropriating the language of PTSD symptoms to cover “any topic you have an aversion to or that causes you to feel any negative emotion you didn’t choose to have” even though I think the latter is a valid concept worthy of consideration. Here is an interesting recent Tumblr post about it, including my reblog with further comments.

Sorry for the full-blown response-effortpost-sized comment — let’s see if WordPress lets me post this comment all in one go.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Frustrating — I quoted the post several times with follow-up comments and no skipped line between them, assuming the quoted parts would show up as quotes because I used q and /q, but I guess that doesn’t work?

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Is this really postmodernism?” should be a self-dissolving question …mostly.

LikeLiked by 1 person