[Note: Just notes.]

I use footnotes[1] in my articles. I didn’t always use them[2], but I started to do so more and more after about a year[3] into my blogging[4]. They have both benefits[5][6] and drawbacks[7], but overall I think the benefits are greater — as long as you don’t… overdo it.

• • •

Notes

[1]

Or maybe they’re endnotes? The distinction disappears when the concept of the “page” becomes obsolete. Before getting a note routine down[3] I tried putting notes at the end of each section instead of the end of the post, which is more like traditional footnotes. It worked ok but it was interruptive[8] and depended on having short sections, almost like pages. In the end I think we’re more likely to keep the word “footnotes” than “endnotes” because a webpage feels like one big page.

[2]

I didn’t use notes in the beginning because there’s no native function in my wordpress editor for inserting and managing them. I have keep track and write the HTML code for them manually. I did work out a routine to do it with a minimum of hassle but it’s still a chore and I had to be convinced of their value to consider it worth doing[3].

[3]

I became a footnote convert after reading David Foster Wallace’s essay A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again in 2016. There and in his massive novel Infinite Jest[9] he didn’t just use notes to add some extra information or clarification, he used them to construct separate strands of narrative, sometimes without which you couldn’t understand the story. He was a “footnote artist” if there ever was one.

[4]

This post took a long time from conception to execution. I had the idea for it just as I was getting into footnotes as a writing device[3] four years ago. Cat couplings was my previous record of taking a long time from start to finish;[10] I started that one back in 2015 before the blog even existed and didn’t go back to finish it until last year. Other posts spend a very short time on the shop floor[11][12], often because I have to get something out while it’s still relevant. Maybe this one took so long because it’s timeless, and therefore easier to postpone.

[5]

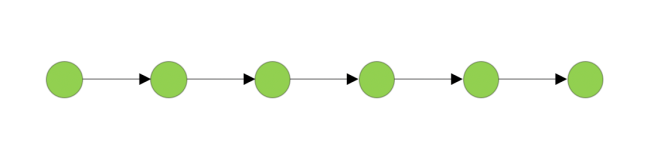

Footnotes means you can cut your cake and keep it too, which takes a lot of pressure off when you lack perfect laser focus[7]. Ideally, a piece of writing has a point to make and gets there truly and cleanly, like this:

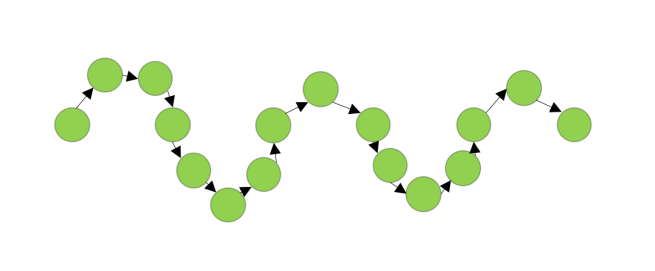

It’s the most efficient way to write but you really must know exactly where you want to go and how to get there, right from the start[13]. You also need perfect discipline too keep your eyes on the target instead of enjoying the scenery too much, or you get this:

I.e. you mess around developing parts in too much detail. “Yeah, yeah I get it, you don’t need an example, personal story or lengthy explication here”, says the hypothetical reader and grows bored. Footnotes to the rescue!

Better. The narrative is rescued and the writer gets to keep their little anecdotes and elaborations.

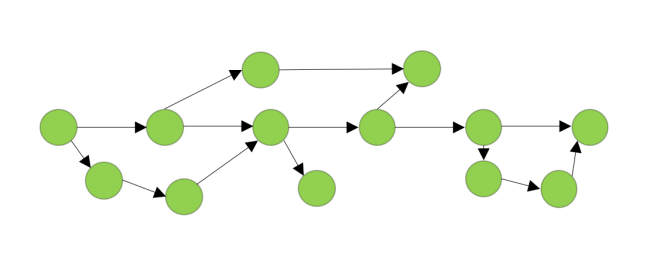

Or you might be the type that does a lot of free association and thus come up with tons of stuff to try bring into the central narrative: “oh and btw I thought of this whichisalsorelevant…”[14].

This easily becomes a hot mess, but with notes it turns into this:

This easily becomes a hot mess, but with notes it turns into this:

Ah.

So, footnotes are a coping mechanism for the less-than-perfectly competent and less-than-perfectly ruthless writer, and I love them for it.

[6]

Sometimes you want to end a post on a particular point where the narrative lands, and having more text after that (if you want to say more) ruins the mood. Luckily you can always turn any afterthought into a footnote and hide it away[15].

[7]

Allowing yourself unlimited footnotes saves you from having to do the hard work to filter, prioritize, and order. Instead you push that job onto the reader, who has to go back and forth[16] to read unnecessary side stuff. It can be presumptous to expect readers to be interested in your beside-the-point-meanderings [17] instead of valuing the reader’s time by going straight for the point[18].

[8]

On the other hand[19], it’s more reader-friendly to put your digressions in footnotes than in the text itself. That way you make the extraneous stuff optional.

[9]

I’ve read somewhere[20] that Wallace specifically told major parts of the story of Infinite Jest[21] in endnotes[16], sometimes many pages long, in order to simulate the fragmented attention[22] characteristic of modern media. If so, he was successful, imo.

[10]

I use semicolons a lot. I know it’s supposed to mark you as a pretentious blowhard but what can you do. I still want to do it[23]. I like them and I’m almost convinced I’m using them correctly most of the time.

[11]

The Romeo and Juliet Fallacy, Turnabout Trash, Postmodernism vs. the Pomoid Cluster, Picking Apart Eugenics, It’s Not So Only, Rant on Arrival and of course my most trivial Signed Google Translate were all quick and straightforward to write. In contrast, A Deep Dive into the Harris-Klein Controversy, Anatomy of Racism, The True, The Good and the Undefined, A Defense of Erisology, and all my book review posts took a whole lot of time, and effort to write, structure, re-structure and line edit. I think more effort translates into better posts on the whole, but the relationship isn’t perfect.

[12]

Once I started to write this it was easy and quick because of how modular it is[24][25][26]. I could just write and write, jot down any random shit[14] I could think of and attach it to whatever vaguely relevant. The format allows anything, even silly jokes[27]. Really, once you’re free from the constraint of having a point and being coherent past the paragraph level, writing is as easy as thinking[28].

[13]

You don’t always start writing with a clear plan. As discussed here, my raw materials for a piece are often just a lump of interrelated thoughts and motifs. Most of my book reviews were easy to start and push to a decent word count because I just wrote down reactions as I read, which was easy because hey, the book itself had established a context[14]. The difficult part came later, when I had to massage it into something with a thesis.

This “patchwork” strategy of writing small parts spontaneously and putting them together into a narrative arc later is one out of three main writing strategies[29].

Another one is to make a rough outline and then elaborate each part.

You need to know where you want to end up and how to get there. If what you’re trying to say is complex and difficult in ways that won’t reveal themselves fully before you write it all out, you’re in for a world of hurt with this technique.

Finally, you can just write it straight through from start to finish, seeing where inspiration takes you.

This is great for exploratory writing, and if you’re good at this you can be an incredibly productive writer. If you’re not good at it, if you have trouble keeping your explorations focused — like me — you risk starting with a lot of enthusiasm and just run off into the wild, get lost and bogged down, and lose interest.

Which is best? Nobody knows and writers have different tastes. For me it depends on the topic and my relationship to it. This footnote piece was perfect for the last(ish) strategy because it allowed me to just write and write without having to keep things on track or come to a natural close. For once that was actually ok.

[14]

I find it hard to write without an established context because I have little trust in my ability to communicate ideas without a lot of introductory groundwork. I feel I need to clue the reader into the entirety of my personal background with the idea I’m about to discuss in order to communicate it accurately. So, I’m often tempted to put a random thought as a footnote rather than as a post of its own because that way there’s already a context and background for that thought and I don’t need to bootstrap one all over again. It’s a way to get a thought out of your system when you just know you won’t prioritize developing it properly later[30].

[15]

This is a weak thought that I probably should have cut, but at the stage in the writing process where I first wrote it I had the idea that more, messier and tanglier is better for this particular post and thus I should throw in everything I had[31]. In retrospect I doubt that was a good idea and ditched some things — but I still kept this one since it allowed me to write this note.

[16]

In other words: hypertext, all the rage in the 90s after the invention of the WWW and the hyperlink. Think of the possibilities! It remains unpopular as an essay/book genre because of how difficult it is to navigate and how unclear the upside is.

[17]

This post is me experimenting with form[32] and free association, mostly to entertain myself. It’s self-absorbed and not reader-friendly[33], and I don’t expect it to be a “hit”[34]. You might call it… anti-viral.

[18]

It’s writer-focused writing, as opposed to reader-focused writing[35][33], and there’s only so much of it you can do before it becomes obnoxious. I’ll dial back on it after this post[36].

[19]

I’m allowing my “on the other hand” tendencies to run wild. I doubt it improves my writing. On the other hand…[17]

[20]

That means it’s true.

[21]

Much of what I’ve read recently that perhaps qualifies as “serious literature” (I’m thinking of Infinite Jest, The Gold Bug Variations, Foucault’s Pendulum and The Glass Bead Game) have something in common: I enjoy thinking about them afterwards a lot more than I enjoyed reading them. My review of Infinite Jest was quite negative but now I look back fondly on it[37]. I wonder why this pattern exists. Do books have to be a chore to read to have complex, rewarding ideas[38]? I really don’t see why[39], and can’t help thinking that only books that are off-putting to casual readers earn the “serious literature” label because status is based on differentiation and exclusion. To be “worthy” it must be disliked by the plebs. How else will liking it mark me as a member of an elite?

[22]

There’s an expectation as a writer that people will read footnotes in context (i.e. click back and forth) but my experience as a reader suggests the opposite[40]. It bothers me a little and it makes notes feel less valuable for things like necessary caveats and clarifications[41] that you don’t really want people to be able to miss.

[23]

Semicolons feel necessary because commas and periods (and exclamation points and question marks) are not enough to delineate clauses in precisely the way I want every time. This is why I — in addition to semicolons — also use a lot of dashes. That’s supposed to be bad as well — a sign you’re not doing enough work to restructure your sentences to fit a commas-and-periods-only framework that’s less taxing on the reader’s mental stack space.

Well, I prefer to see it (and also my habit of making whole phrases work like adjectives by hyphenating them (see last sentence for an example (also did I say I’m a fan of parentheses?))) as a way of writing closer to how I’m actually thinking rather than force thinking to fit standards of good writing practice[42].

[24]

It was easy partly because I wrote it on paper[43]. Paper is easier than computer, which is easier than phone. There’s something about the ease and directness of the interaction. With paper there’s no friction, no “interface bureaucracy” to deal with. You can just funnel thought directly from brain to pen, and you don’t have to think about errors in the process. It’s common to mistype on a phone, rarer on a laptop, and almost nonexistent on paper. I wrote about it in this post from when I was without a phone for a week:

Before I had a phone and a laptop I used a lot of notepads. I have a whole stack hidden away somewhere, full of lists, sketches, ideas, designs for drawings, games, languages, things to make and build. Now my life has become increasingly free of both paper and boredom and I hardly use any. I do have quite a lot of notes in Evernote, but it’s not the same. You don’t doodle on a phone. Playing with thoughts on paper is something different. There’s no pane of glass with a programmed little trading zone defining the set of possible actions, coercing you into a button-pushing pidgin. Pen on paper is my mother tongue.

Its physicality also has value in a world where pixel patterns are the common form of artifact existence. As I wrote down the bits and pieces that were to become this article I felt a disproportionate, unreasonable excitement at the prospect of using more paper. I wanted to write lists on paper — books I wanted to read, movies I wanted to watch, maybe a journal.

[25]

My blogposts take a lot more time to write than the stuff I do for work, probably because blogging is a lot more personal to me and I, you know, care. When you write for work you just gotta push something out. You look for an angle, a narrative, anything serviceable, and I find that what comes out is driven more by “sounds good” logic than by your actual beliefs.

I recently had a reporter from a small business magazine email me to ask about a piece I’d written for work. It made me a little uncomfortable and referred him to my boss instead. I didn’t feel I could justify or elaborate on what I’d said with any confidence because there were no real ideas there underneath, no expertise or considered views to draw on. I’m just a professional dot-connector, man. “Eeehhh, the conclusion matches the numbers[44] ok and it sounds good enough” is the real reason I wrote what I wrote but you can’t tell a reporter that.

When you have a job to do you have to come up with something and make it sound convincing, and whether or not it holds up under scrutiny is secondary, because nobody looks and nobody cares. Nobody wants to read a consultant hedging and problematizing for paragraph after paragraph. That’s what you hire a consultant to avoid. So you write the best-sounding thing you can under the circumstances and push it out, disassociating yourself from it psychologically as it’s written in your employer’s name and not your own.

[26]

I do admit it was a pain to keep together once I started editing.

[27]

A note can even point to itself[27].

[28]

Writing difficulty increases faster than length. A 3000-word article is more than ten times the work of a 300-word Twitter thread, and a 90.000-word book is more work than 30 3000-word articles. I know that because I’ve written several books worth of blog posts and I have yet to write several books[45].

A book needs more management than a blog post for the same reason a large corporation needs more management than a small family firm. Sometimes I wonder if this feeling is an illusion and everything would work out fine if I stopped worrying about it and just wrote. Then I remember that writing without a plan has weaknesses already on the blogpost level[13], and that I don’t particularly like books that lack an overall thesis.

[29]

I used to write music[46][47] and I think there’s a lot of parallels between different ways of writing music and different ways of writing essays.

I’ve personally never got the musical equivalent of writing straight through to work. I’m not musically intuitive enough to free-wheel like that[48]. Case in point: fugues are difficult as hell and every time I’ve tried to write one from beginning to end I’ve gotten stuck and given up. The equivalent of making disconnected small parts and putting them together later work far better for fugues because the rules that define the style are finicky on the detailed level but allow for almost anything in terms of overall structure.

The closest equivalent of outlining is probably writing chaconnes or passacaglias, where a bassline repeats throughout the whole piece and melodies change above it (think Pachelbel’s Canon in D). The most “outlined” musical piece of mine was based on the famous bassline from Seven Nation Army where I had a long chord progression on four repeats of that riff, all repeated a number of times, finally decorated with a single melody line on top.

Just like outlining an essay works fine when you know exactly what each part should contain it’s rather easy to outline music when you have few moving parts and a strict hierarchical relationship from the fixed to the flexible (e.g. bassline → chords → melody). When I tried to outline a mini-sonata with both piano and string parts freely moving it ended in frustration and mediocrity.

I’ve tried different formats and rule schemes that limit the degrees of freedom, but it’s tricky to get the balance right[49] — too little structure and you have to be intuitive (which I’m not) or too much and it sounds stale, repetitive and mechanical, or doesn’t work at all because the rules force everything to clash with itself.

[30]

There’s a “good is the enemy of perfect” problem here. Getting thoughts out of your system feels good but it also means they exert less pressure on the inside of your head and are therefore less likely to get a proper treatment later.

[31]

It’s like an extreme, perverted form of refusing to kill your darlings[7]: it’s actively breeding darlings.

[32]

I also used footnotes for form experimentation in this article. It has problems exactly because of how stream-of-consciousness and disjointed it is, and I think the basic, noteless piece would’ve been better if I had actually fixed it up properly instead of doing what I did.

[33]

This is a problem with nonlinear writing I’m now experiencing for the first time: unintentional parallelism. I’m reaching the same ideas from different directions and I’m not quite able to tie it together well. Too much of that and a tangled[16] post like this feels repetitive and disorganized[50] rather than elegantly complex. I’ve tried to remove most parallelisms but it was hard without heavy restructuring, which I avoid because it leads to even more restructuring.

[34]

I have, however, been told that I’m an unusually engaging navel gazer. *sniff*

[35]

A lot of creative people have this issue. To a creative person self-expression is paramount, and everything you make is supposed to be a true reflection of your inner self[51]. Sure, you want people to like what you make, but the purpose is not, ultimately, to please[52]. To be, in (horrible) business[53] parlance, customer-focused, and change your offer to what sells, is to miss the point of creative expression[54][55].

[36]

Promise.

[37]

As I predicted I would.

[38]

To be fair there can be benefits to presenting things in a difficult way[56][57]. For example, while I felt The Glass Bead Game could’ve been much shorter without losing any important ideas, I imagine it wouldn’t have had the same effect on me if it had been more compressed. Length forces you to spend time with a text, to make it a part of your life for an extended period, and that way its ideas will naturally take up more space in your head. It’s a way to make things stick better[58].

[39]

I keep thinking of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy here. It’s very popular, while also complex and with, I think, comparable philosophical depth to the other novels mentioned if you make the effort to look for it. For example I’d argue it exemplifies the postmodern condition in both form and content (and published two years before the book with that name). However, it’s not taken seriously as a literary work and I think part of it is that it’s fun and popular.

[40]

I expect most readers to go through this post from start to finish[59] (if they care to read the whole thing at all) and unfortunately won’t appreciate its sublime structure[60][27].

[41]

Scott Alexander mentions an alternative (end of section 3 here) that keeps the note text in its “proper” place: you make it a whole paragraph in parentheses.

(It looks like this.)

It would be good if both that and traditional notes were in common use[61] so we could mix freely. Greater room variety in writing conventions is a good thing.

[42]

One of the big benefits of having a personal blog as opposed to being a professional writer is that you can write anything you want, in any way you want[62].

[43]

It wasn’t intentional. It’s just that I went away over summer for three weeks and forgot to bring my charger, so after the first few hours no more laptop writing for me. It turned out well and I should remember that for future reference.

[44]

While real, the numbers are selected (cherry picked?) for making sense. If you want you can almost always choose to put together contradictory, ambiguous and self-problematizing sets of stats instead, but nobody wants to pay to learn that “this is complicated and uncertain, more research is needed”. That shit comes free on sci-hub.

[45]

I have in fact written one book: a 55000-word comic mystery novel, finished at the age of 18. I reread it a couple of years ago and it’s truly awful. The only good things I can say about it is that the plot does make sense and I still support its moral.

[46]

I don’t do it anymore because I prioritize using my free time for blogging. Making music is great but I’m comparatively worse at it and don’t get the same social validation from doing it. It’s hard to be purely self-motivated.

[47]

One benefit of composing is that you get music perfectly tailored to your own tastes. It feels weird to say it but I really love listening to my pieces.

[48]

I can improvise melodies but I can’t write them down in musical notation because I don’t have a good ear and I can’t sight read. Instead I go by theory plus trial and error. If I were to write essays like I compose music I’d write one sentence at a time, read it back to myself to see if it makes sense, and if it doesn’t try altering it based on things I’ve learnt about language, then read it back to myself again, etc.

[49]

Maybe it’d be easier if I just wrote normal songs with a verse-chorus structure and a vocal melody above a chord progression instead of insisting on obeying complex polyphonic forms popular among the 18th century aristocracy.

[50]

I guess there are standards for good and bad hypertext essays — standards that are mostly unexplored so far(?), and one of them seems to be “avoid parallelisms”[63].

[51]

You could say that creative works has part of the creator’s soul in them. In On Chords, Maps and Effects in Art I called this the “good” version of “horcruxes” from the Harry Potter books:

In the HP universe, horcruxes are parts of your soul you embed into objects to keep you from passing on when you die. In the books, horcruxes are dark, evil magic. The way to make one is to tear your soul apart by an act of unspeakable evil. The real world, luckily, isn’t that brutal. You can embed parts of your soul in objects not by mutilating it but by nurturing it and letting it flow over. Works of art are a way for your soul to reshape part of the physical universe in its own image and thereby extend and perpetuate itself. This is why a major part of great art is being something that (for reasons like unique skills, experiences or insights) no one else could have made.

[52]

I had lunch with an old friend a while back, a business-y, entrepreneurial, successful career type guy. He pitched an idea to me with the argument: “I know you, you don’t want to sit for years in a room and work something out that nobody cares about, right? You want to make something that a lot of people use!”

I agreed to think about his idea but I just couldn’t bring myself to care. It might indeed have been something a lot of people would’ve used, and I want that, sure, but it’s not enough to motivate me. It was a boring, fundamentally uncreative idea. It doesn’t feel satisfying to make something successful if that successful thing isn’t a genuine expression of my own creative impulses — if it isn’t something that I like, that I’m proud of, and that represents me in the world[51] the way I want to see myself.

[53]

This is a constant struggle when working within a business. The customer is King, and everything is about what they want. I get it. I get that is has to be like that, but my bones keep fighting it. I’ve received blank stares from colleagues when trying to express how I think something can be valuable separately and in addition to providing instrumental value to a customer.

[54]

Good art requires a balance of power between creator and audience. There must be a strong individual artistic vision, and “target market” concerns have to be secondary to not produce anxiously watered down focus group fare. On the other hand[19], something must anchor you to a decent sized audience if the whole enterprise isn’t going to become masturbatory, incestuous and ultimately irrelevant. Art is communication, and for that it must be genuine from the creator’s side, and accurately and willingly received from the audience’s side.

[55]

I think this is a big part of why creative types tend to be politically left-wing. Being quick and eager to adapt to customer demand is unnatural and uncomfortable behavior for a lot of us, and this makes you feel, deeply and viscerally, that the market doesn’t value things correctly. A lot follows from that feeling.

[56]

Difficulty can be used to fake profundity. You can get an “insight buzz” by reading something genuinely insightful about the world, but you can also get one by solving a strictly meaningless puzzle (like a sudoku)[64][65]. If we wrap a mundande observation in writing so convoluted that it becomes a puzzle to decipher we’ll get a small insight buzz when we finally make sense of it — one which we might easily confuse with the uncovered message itself being insightful. It’s the mental equivalent of artificial sweetener[58].

[57]

Difficulty — when there’s substance behind it[56] — does reward repeat reading, which is good[66]. If something doesn’t keep giving the second time it doesn’t contain much to chew on.

[58]

I’m[67] not sure there’s a sharp line dividing helpful[38] and obfuscatory[56] difficulty. You can get an idea to feel bigger in the mind of a reader more than it otherwise would, and whether this is deceptive or not depends on how valuable the underlying idea actually is — which is highly subjective.

[59]

I did make some notes a bit hard to understand without their context to entice people to jump back and forth[68].

[60]

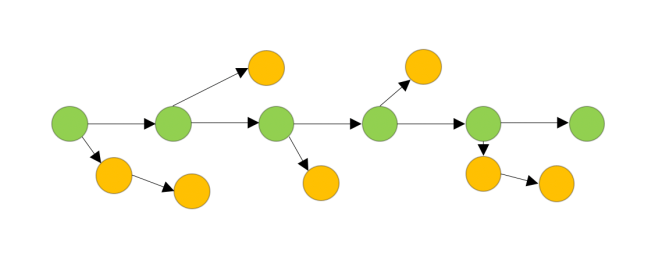

I love information visualization, so here’s a picture of this post’s link structure:

Looks decent but it doesn’t “pop”. How about a network?

You can spot a few key nodes that spawn a lot of additional thoughts, some that are pointed to from several directions, quite a few that go nowhere at all, several long chains, and even a few closed cycles of varying size[27].

This network picture was the very last thing I did on this post, and I loved finally getting to see the structure I’d become semi-familiar with during writing and editing. It was like seeing a map of a city you’ve learned to find your way in only by walking around.

[61]

I actually stumbled upon an example of it being used — twice in the same article — by friend-of-the-blog writer Tom Chivers. Is it more common than I think?[68]

[62]

On the other hand[19], this allows me to keep bad habits that prevent me from becoming a better writer. Some pushback is probably good for everybody[54].

[63]

Trees already know this[68]:

[64]

Mystery novels exploit this part of our psyche like a drug. But at least they deliver the hit in the end, which makes them better than typical “Mystery box” storytelling that just dangle things in front of you and then try to distract you from the fact that there’s nothing in there[68].

[65]

Making something opaque so it seems more interesting and attention-worthy is a common trick. I remember an ad once that was just plain text written upside-down. Of course that makes you wonder what it says, so I wound up carefully reading some boilerplate copy about their new yoghurt or whatever it was. Well played[68].

[66]

I once read[20] “If something is worth watching once, it’s worth watching twice” about movies, and I think it’s spot on about reading materials as well. Note the corollary: if it’s not worth returning to and explore again, it’s not good enough to pick up in the first place. Doesn’t mean you actually have to read/watch everything twice, but things should hold up for a revisit or two.

[67]

I noticed that I do start a lot of sentences with “I”, which you’re not supposed to do. I understand that it sounds self-centered. I sort of disagree: I use it to emphasize how something I say is my own assessment, conjecture or opinion, and not necessarily valid for everyone else — and thereby express a kind of humility. I do feel, on the other hand[19], that this reflects self-centeredness on another level: I assume that my personal assessment of things are worth enough to write down and publish online.

[68]

Near the end there are more and more notes that don’t point to anything else. You could call them “dead ends” but I prefer “leaves”. It suggests vitality, and that they have value in themselves and are not just a way to take the reader from one point to another and contribute to the conceit of this post[69].

[69]

Number 68 was supposed to be the closing note, but I felt I had to add a little postscript.

I had only a vague notion of what I was going to write when I started this. There was only the idea and maybe four or five notes in my head. I ended up with 69 of them, which is way more than I expected. I had thought maybe 15-20 — no need to run away with it. But it ran away with me: I scribbled in my notebook, furiously, indulging every whim and following every tangent, pulling every thread, with nothing standing in my way! So alive! This is was writing could be — lightning straight from head to paper — if only it didn’t have to fit a linear, thesis-driven mold.

I discussed small hypertext essays as a “genre” above (I won’t link back to it, I’m past that now) and afterwards — having seen the resulting network and all — I wonder if diligent practice can make you genuinely good at it to the extent that you can really make it work, other than as a joke. Maybe I’ll try it again some time, with a better topic.

In 30 Fundamentals I recommended that every writer makes a piece like it, and I suggest the same here. Try this! It’s fun, very different from more structured writing, and it reveals quite a lot about your thought patterns and preoccupations. And getting to see the network in the end (if you have access to some software to make it for you) is so satisfying.

Did you enjoy this article? Consider supporting Everything Studies on Patreon.

Take the graphical network from note 60, and simply place each particle of writing (paragraph, note, whatever) onto the corresponding node. Absent technological limitations (e.g. the number of characters or particles that can be presented side-by-side, due to minimum angle per character and minimum number of characters per line for readability, and maximum angle the medium (whether sheet of paper or screen) can subtend) this would be the closest to reproducing the structure of thoughts in the author’s head. To the extent the structure of the graph can be represented in 2D with no unduly long linkages, each particle would have physically local the entirety of its logical context. Even better, both incoming and outgoing linkages would be visible, which would help with e.g. abstract definitions of concepts and concrete examples. If the direction (never mind “direction”, instance-of is only one type of relationship) was consistent throughout the work, this would allow readers to e.g. focus on one or the other type depending on their personal habits of mind.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Near the end there are more and more notes that don’t point to anything else. You could call them “dead ends” but I prefer “leaves”. It suggests vitality, and that they have value in themselves and are not just a way to take the reader from one point to another and contribute to the conceit of this post”

If you haven’t read House of Leaves, you should try it out. You sound like you would enjoy it 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve heard of it being interesting, but also creepy and unsettling and that isn’t really my thing.

LikeLike

“…supposed to mark you as a pretentious blowhard…”

I’m more than 95% certain that persons with above-average-value things to say expend more energy trying *not* to sound pretentious than the other way ’round.

LikeLiked by 1 person

(carefully graphing out post’s structure as I read along)

(get to number 60)

Well, damn it.

——————————

Many people of my generation are familiar with this exact structure, in the form of “Choose Your Own Adventure” books. Recently there was a silly but high-quality adaptation of Hamlet with the same structure, titled “To Be or Not To Be”. Especially recommended if you have kids under 13.

—————————–

Re: 47, I notice that I enjoy reading Past Me’s nonfiction, but not Past Me’s creative writing. I wonder why.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow that’s dedication! I hope you didn’t expect too much from the emerging network. There wasn’t really a plan to it.

I actually had a mention of choose-your-own-adventure books in an earlier version (I had a few of those as a kid) but it didn’t make the cut.

LikeLike